With temperatures climbing from climate change, the mountain pine beetle is now moving to higher elevations on mountain slopes, and is a “rising threat” to the whitebark pine, according to a University of Wisconsin-Madison study published today, Dec. 31, 2012, in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The whitebark pine is found mainly in the Rocky Mountains and Coast Range of British Columbia and into the northern United States.

In the US, there there have been a number of studies of pine beetle infestation of the whitebark pine. In 2011, the Seattle Times reported

A study in the mid-2000s showed whitebark trees had declined by 41 percent in the Western Cascades. Tree declines throughout Washington and Oregon hovered around 35 percent. In the coastal range and the Olympics, blister rust infection ranged from 4 to 49 percent. Nearly 80 per cent of the whitebark in Mount Rainier National Park are infected. Whitebark deaths in North Cascades National Park doubled in the last five years.

The Seattle Times also quoted the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service reporting in 2007 that beetles killed whitebark pine trees across half a million acres in the US West — the most, at the time, since record-keeping began. Two years later, beetles killed trees on 800,000 acres.

Ken Raffa, a University of Wisconsin -Madison professor of entomology and a senior author of the new report says.”Warming temperatures have allowed tree-killing beetles to thrive in areas that were historically too cold for them most years. The tree species at these high elevations never evolved strong defenses.”

A warming world has not only made it easier for the mountain pine beetle to invade new and defenseless ecosystems, the scientists say, but also to better withstand winter weather that is milder and erupt in large outbreaks capable of killing entire stands of trees, no matter their composition.

“A subject of much concern in the scientific community is the potential for cascading effects of whitebark pine loss on mountain ecosystems,” says Phil Townsend, a Univeristy of Wisconsin-Madison professor of forest ecology and a senior author of the study.

The mountain pine beetle’s historic host is the lodgepole pine, and it was widespread lower elevations until the pine beetle infestation began to spread in the late 1990s. The pine beetle which are about the size of a grain of rice, played a key role in regulating the health of a forest by attacking old or weakened trees and fostering the development of a younger forest after the older trees died or were destroyed by fire.

However, recent years have been characterized by unusually hot and dry summers and mild winters, which have allowed insect populations to boom. This has led to an infestation of mountain pine beetle described by the scientists as “possibly the most significant insect blight ever seen in North America.”

A BC government report A History of the Battle Against the Mountain Pine Beetle 2000-2012 says:

Over most of the Interior, extreme winter weather (colder than minus 35 Celsius for at least several days or even weeks) historically killed most of the pine beetle population, limiting the duration of, and damage from, periodic epidemics. Such a wide-spread weather event has not occurred in the B.C. Interior since the winter of 1995/96.

The lodgepole pine co-evolved with the bark beetle, ad so it evolved chemical countermeasures, volatile compounds toxic to the beetle and other agents that disrupt the pine bark beetle’s chemical communication system.

According to the Wisconsin study, despite that robust chemical defense system, the lodgepole pine is still the preferred menu item for the mountain pine beetle, suggesting that the beetle has not yet adjusted its host preference to whitebark pine. “Nevertheless, at elevations consisting of pure whitebark pine, the mountain pine beetle readily attacks it,” says Townsend.

The good news, he adds, is that in mixed stands, the beetle’s strongest attraction is to the lodgepole pine, suggesting that, at least in the short term, whitebark pine may persist in those environments.

However, the 2007 US study quoted by the Seattle Times also warned that unlike lodgepole, whitebark pines produce few seed cones and do so late in life, so they “aren’t set up to survive massive slaughter.”

The new study, conducted in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, also showed that the insects that prey on or compete with the mountain pine beetle are staying in their preferred lodgepole pine habitat. That, says Townsend, is a concern because the tree-killing bark beetles “will encounter fewer of these enemies in fragile, high-elevation stands.”

Whitebark pine trees are an important food source for wildlife, including black and grizzly bears, and birds such as the Clark’s nutcracker named after the famed explorer and which is essential to whitebark pine forest ecology as the bird’s seed caches help regenerate the forests.

(According to Wikipedia Clark’s Nutcrackers each cache about 30,000 to 100,000 each year in small, widely scattered caches usually under 2 to 3 centimetres of soil or gravelly substrate. Nutcrackers retrieve these seed caches during times of food scarcity and to feed their young. Cache sites selected by nutcrackers are often favorable for germination of seeds and survival of seedlings. Those caches not retrieved by time snow melts contribute to forest regeneration. Consequently,Whitebark Pine often grows in clumps of several trees, originating from a single cache of 2–15 or more seeds. Douglas Squirrels cut down and store Whitebark Pine cones in their middens. Grizzly Bears and Black Bears often raid squirrel middens for Whitebark Pine seeds, an important pre-hibernation food. Squirrels, Northern Flickers, and Mountain Bluebirds often nest in Whitebark Pines, and elk and Blue Grouse use Whitebark Pine communities as summer habitat. )

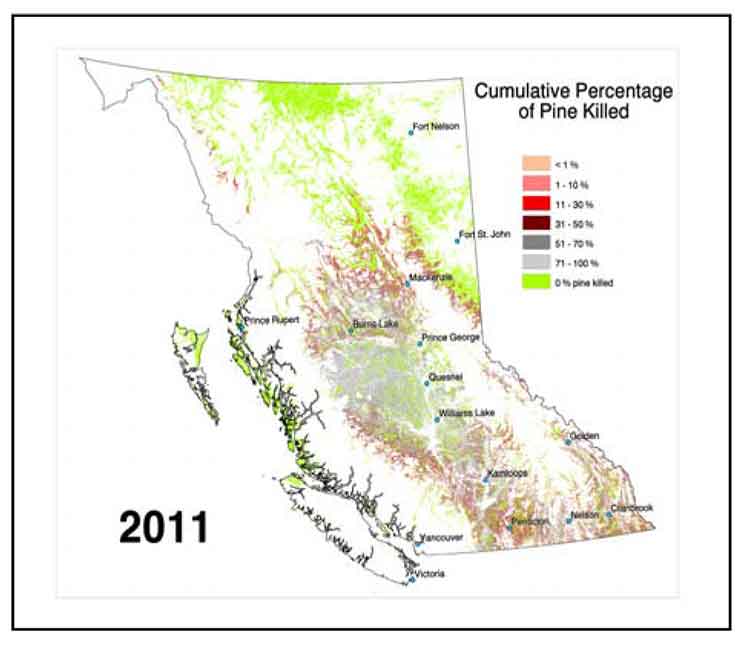

The BC government report says the pine beetle epidemic has now killed an estimated 710 million cubic metres of commercially valuable pine timber, 53 per cent of all such pine in the province. The rate of damage has been slowing for several years, but is projected to grow to 58 per cent by 2017 (to 767 million cubic metres).

Both the provincial and federal governments have spent hundreds of millions of dollars on the mountain pine beetle epidemic, beetle killed pine forest is more vulnerable to forest fires, and it is possible that the drier wood from beetle killed wood is responsible for the explosions at mills in Burns Lake and Prince George.

The BC government report says

B.C. has been battling the mountain pine beetle epidemic since the year 2000. From 2001 through 2004, the focus was on limiting the spread of the infestation and harvesting infested and susceptible pine stands. Not content to wait for frosts and winter cold spells that normally control the beetle, the Province took other steps to control the beetle’s spread. However the infestation continued to spread dramatically to 2007.

Throughout last decade, government and industry concentrated on salvage harvesting, to recover maximum economic value, and the reforestation of the dead stands. The provincial and federal governments invested hundreds of millions of dollars in mitigating the infestation’s impacts, in developing new markets for beetle-killed lumber, and in creating economic strategies for the future.

At the same time, the forest industry invested in adapting its harvest and milling technologies to the ever-changing forest resource, using the knowledge and experience gained from a significant, but much smaller, beetle infestation that hit the Cariboo-Chilcotin in the mid-1980s.

These actions have placed the industry, government and communities in the best position to address the next phase of the epidemic, as harvest and milling activities inevitably start declining.

2 thoughts on “Pine beetle moving higher into mountains, now “rising threat” to whitebark pine, study says”

Comments are closed.