The August 2011 issue of National Geographic is bringing welcome worldwide attention to the  northwest coast of British Columbia and the issue of the Enbridge Northern Gateway Pipeline and the plan to ship oil sands bitumen to Asia through Kitimat.

northwest coast of British Columbia and the issue of the Enbridge Northern Gateway Pipeline and the plan to ship oil sands bitumen to Asia through Kitimat.

There are two articles, “The Wildest Place in North America, Land of the Spirit Bear,” an excellent article which introduces much of the world to the beauty of the white Kermode Spirit Bear and “Pipeline through Paradise,” which unfortunately is a superficial sidebar and in one case glaringly inaccurate.

As might be expected, the initial reaction from the environmental movement was euphoric, beautiful images of the Spirit Bear, the coast and the mountains, a detailed look at the ecology of the Great Bear Rainforest and the white bear’s place in the forest which is little known outside this region. (A couple of years ago, I was speaking to some local aboriginal carvers and engravers in Santa Fe, New Mexico, who were fascinated by what little I knew about the Spirit Bear–they had never heard of it).

The second article, “Pipeline through Paradise” has also drawn praise from many people who oppose the pipeline.

As also might be expected, Enbridge was not so happy. Company spokesman Paul Stanway told the Edmonton Journal

“We spent a lot of time and effort with National Geographic, and in the end they didn’t say very much about the information we provided,” spokesman Paul Stanway said.

“They were given extensive information about the safety features we would employ along the pipeline route and the maritime portion….”

In the Prince Rupert Northern View, Stanway also questioned the National Geographic’s editorial process.

The company says that its “not disappointed by what’s in the article, more by what is not said in the article,” meaning that while the National Geographic spent weeks doing interviews and fact-checking with Enbridge, the magazine decided to leave most arguments out of the story.

National Geographic, quite rightly, has the editorial mission of alerting the world to environmental dangers that much of the media either ignore or dismiss as boogeymen. The magazine bases its articles on sound science and, within that parameter, is fair to all sides of an issue. .

It’s unfortunate that the National Geographic’s normally high editorial standards are not present in Barcott’s pipeline article. While “he-said-he-said, tell-both-sides” journalism often obscures real issues, especially in this era of professional spin, Enbridge does have a point, the company is given short shrift in the story with just one quote.

Even worse is one glaring error that will certainly call into question the credibility of the entire article (especially among proponents of the pipeline), where Barcott says “The government has already approved a fleet of liquified natural gas tankers to call at nearby Kitimat in 2015.” an error that may be repeated on the magazine’s maps of the proposed bitumen and natural gas pipelines.

While the arcane approval process of the National Energy Board may be confusing to many in the public, it is the job of journalists to figure it out. It should have been very easy for the National Geographic fact checkers to discover that NEB has not yet approved the export licence for the KM LNG project. In fact, the NEB hearings in Kitimat only began on June 6, 2011. Given the deadlines and printing processes for a high quality magazine like National Geographic, it is highly likely that the article was ready for the presses even before the June 6 hearings began. While the Pacific Trail gas pipeline has had approval by a BC provincial environmental review, (so the map is technically correct but given the article one has to wonder if the accuracy is inadvertant) there could be no terminal at Kitimat (even though it is under construction) nor the “a fleet of liquified natural gas tankers” until NEB grants the export licence and the NEB can, if it wishes, put conditions on the export licence that could govern how those tankers operate.

While it is expected that the NEB will grant the licence, jumping the editorial gun is not recommended for any journalist.

The other critical flaw in the article can be seen in Stanway’s comment to the Edmonton Journal, which permits Enbridge to dismiss the concerns of the people of Kitimat and back along the pipeline route.

(Emphasis is mine)

“We don’t believe tankers going in and out of Douglas channel (between Kitimat and the ocean) would interfere with that in any way, since Kitimat is outside the Great Bear area,” Stanway said.

The background to the National Geographic article is familiar to nature photographers, probably less so the general public. Last year, in early September, the International League of Conservation Photographers, which includes some of the best nature photographers in the world came to shoot along the coast of the Great Bear Rainforest.

Stanways statement is just what I was worried would happen when I first heard about the Great Bear photo project last fall

Here is how ILCP describes why they came

The International League of Conservation Photographers (iLCP) has teamed up with Pacific WILD, the Gitga’at First Nation of British Columbia, LightHawk, TidesCanada, Save our Seas Foundation, Sierra Club BC, and the Dogwood initiative to carry out a Rapid Assessment Visual Expedition (RAVE) in the Great Bear Rainforest of British Columbia. We are focusing our energy and cameras on this pristine region in response to plans by several large multinational companies to build a pipeline for heavy crude oil from the Alberta tar sands across British Columbia to the coast of the Great Bear Rainforest.

The 14-day expedition to the Great Bear Rainforest called upon 7 world-renowned photographers and 3 videographers to thoroughly document the region’s landscapes, wildlife, and culture. The RAVE provided media support to the First Nations and environmental groups seeking to stop the proposed Enbridge Gateway pipeline project (and thus expansion of the tar sands) and to expose the plan to lift the oil tanker ship moratorium.

ILCP was basically piggy-backing on the years of campaigning to save the Great Bear Rainforest, a perfectly legitimate strategy.

Along with a couple of film companies, National Geographic was one of the media sponsors of the trip to the Great Bear which, according to the ILCP website, took place form September 1 to September 12. Another sponsor was the King Pacific Lodge. All the sponsors had legitimate conservation concerns along the coast, but there were no inland sponsors or First Nations involved.

It is perfectly true that the coastal First Nations and the Great Bear Rainforest are the most threatened by any potential spill from a bitumen carrying tanker. As Frank Brown, of the Hielsuk First Nation at Bella Bella, said at the rally outside the NEB hearings in Kitimat last August 31, his people “risk everything and gain nothing” from the pipeline project and the tankers. The coast won’t even get the handful of jobs that will come to Kitimat.

The ILCP trip appears to have an unfortunate, and perhaps unforeseen consequence that is echoed in the National Geographic articles and in that statement by Enbridge’s Stanway “since Kitimat is outside the Great Bear area,” the Douglas Channel, including its estuaries, Kitimat, Kitimat River and the areas to the east all the way back to the Rockies are less important than the Great Bear Forest itself.

Both the ILCP campaign and now likely the National Geographic article are apparently already creating the idea that Great Bear Forest is the only major pipeline related environmental issue in this region.

Both the ILCP campaign and now likely the National Geographic article are apparently already creating the idea that Great Bear Forest is the only major pipeline related environmental issue in this region.

That was certainly was the impression I got last spring when I attended the North American Nature Photographers Association convention in Texas. Everyone at the conference had heard about the Northern Gateway Pipeline. Most people seemed to know there was a town called Kitimat but they knew little more and knew nothing about Douglas Channel or the wild mountains to the east along the pipeline route. Everyone talked just about Great Bear. While some of the photographers at the NANPA convention affiliated with the ILCP were interested and enthusiastic about a Kitimat or wider BC perspective on the story, one well known and highly talented photographer who was part of the ILCP Rave and had been down in the Great Bear, when I brought up in a conversation Douglas Channel, the Gilttoyees and Foch, rather rudely told me I didn’t know what I was talking about.

Now it is perfectly legitimate and even valuable if the ILCP wants to focus on the Great Bear Rainforest, photographing the remaining pristine regions of the world is their mandate.

It should also be noted that one ILCP associate photographer, Neil Ever Osborne, has spent the summer flying over the route of the pipeline, capturing magnificent aerials.

The long term problem is that National Geographic and ILCP are likely setting the media agenda. Most media organizations, if interested, but limited by shrinking budgets, overworked editors and lazy, greedy management will follow their lead and just report on the Great Bear Rainforest and ignore the rest of northern BC. It’s not just Kitimat that is beyond the Great Bear boundaries, and is being ignored, Haida Gwaii is also outside the Great Bear and could be damaged by an oil spill.

When it comes to journalism, there is no excuse for National Geographic. Although the society doesn’t have the almost unlimited budgets they had in past decades, the National Geographic Society still has a lot more money than most journalistic organizations. If the National Geographic was going to do a story on the Northern Gateway pipeline, why did its reporter stick strictly to the Great Bear area?

Let’s look at the dates. According to ILCP, the Great Bear photo shoot began on September 1 and ended on September 12. The National Energy Board’s first community hearings on the pipeline were in Kitimat on August 31, a fact well known across the region and well publicized by the NEB. Enbridge had scheduled a public meeting in Kitimat on September 22. That meeting was widely advertised in local media across the region and promoted on Enbridge’s website.

I covered the hearings on August 31 and the rally outside. Apart from a couple of activist documentary producers who were filming the hearings, the only reporters who attended were based in here in Kitimat (while First Nations representatives from the coast and inland did attend both the hearings and the demonstration) On September 22, only the three locally based reporters, including myself, showed up for the Enbridge community briefing.

(National Geographic is not only the other media at fault. With a couple of exceptions, reporters from the PostMedia chain and other Canadian media continue to cover Kitimat from their desks in Toronto, Calgary and Vancouver.)

If the assignment editors at National Geographic had had the vision to widen the focus beyond the Great Bear, or if Barcott had bothered to look beyond the British Columbia coast, he could have come to Kitimat on August 31 for the NEB hearings, the day before the ILCP shoot began or, after the shoot, he could have stuck around for another 10 days for the Enbridge presentation.

At the September 22 meeting, Enbridge officials outlined their plans and their planned precautions. Some local people, people with knowledge of the Channel, and men from the RTA aluminum smelter who asked highly technical questions about pipeline metal and pipeline construction, challenged Enbridge on those plans. Covering either event would have created an article that would have met the editorial objections that Enbridge has raised.

A trip up Douglas Channel, a trip into the mountains the pipeline will cross, a visit to Smithers and the Bulkley Valley, (even if the article didn’t cover all the way east to Alberta) would not left the unfortunate and mistaken impression that the only part of this world that counts is the Great Bear Rainforest.

A little more knowledge of the complexity of the issue, which could have been gained by speaking to NEB officials in August, would not have allowed the error about the approval of the LNG projects to make it into print.

Barcott could not only have seen a lot more of this region. he could have attended the hearings or the public meeting and would have produced a far more accurate, credible and nuanced article.

The last time National Geographic visited Kitimat was in 1956, with a major article when Kitimat was considered a town of the future, 55 years ago. Perhaps, in the interests of journalistic accuracy and credibility, National Geographic should come back before 2066.

The last time National Geographic visited Kitimat was in 1956, with a major article when Kitimat was considered a town of the future, 55 years ago. Perhaps, in the interests of journalistic accuracy and credibility, National Geographic should come back before 2066.

Editor’s note: As the result of feedback on this article, I should note that I am not singling out the environmental movement nor nature photographers. While the energy companies directly involved in both pipeline projects are offering various incentives to the communities involved including Kitimat, as a whole, the Alberta oil patch keeps talking about Kitimat as their gateway

and their key to Canadian prosperity. The majority of Albertans pushing the projects will never come here and will never have to deal with the consequences of any problems. The energy industry has to realize that people who live here want good, sustainable jobs and to use the income from those jobs to enjoy the region’s magnificent wilderness. The solution is for a wider viewpoint of the issues from the BC coast to northern Alberta. Whatever position a journalist takes on the issues, don’t keep ignoring the town and port of Kitimat, the apex of the story. (For example, this page was tweeted as I was writing this, a social media site for “professionals” discusses the Kitimat LNG project solely from the point of view of energy industry consultants.)

Related links

Indian Country Media Network: Gitga’at and Spirit Bear Grace National Geographic’s August Cover

CTV Anti-pipeline lobby praises National Geographic story

Canadian Business (Canadian Press) National Geographic calls Northern Gateway a pipeline through paradise

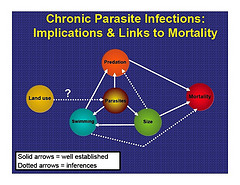

The study, which took place on the West Fork Smith River concluded that heavy loads of parasites can affect salmon growth, weight, size, immune function, saltwater adaptation, swimming stamina, activity level, ability to migrate and other issues. Parasites drain energy from the fish as they grow and develop.

The study, which took place on the West Fork Smith River concluded that heavy loads of parasites can affect salmon growth, weight, size, immune function, saltwater adaptation, swimming stamina, activity level, ability to migrate and other issues. Parasites drain energy from the fish as they grow and develop.

The last time National Geographic visited Kitimat was in 1956, with a major article when Kitimat was considered a town of the future, 55 years ago. Perhaps, in the interests of journalistic accuracy and credibility, National Geographic should come back before 2066.

The last time National Geographic visited Kitimat was in 1956, with a major article when Kitimat was considered a town of the future, 55 years ago. Perhaps, in the interests of journalistic accuracy and credibility, National Geographic should come back before 2066.