New regulations under the Fisheries Act that was revised by the Harper government’s omnibus bills go even further in gutting protection for fish habitat in Canada, according to an analysis by scientists released Friday.

The changes to Canada’s fisheries legislation “have eviscerated” the ability to protect habitat for most of the country’s fish species, the scientists, John Post, at the University of Calgary and Jeffrey Hutchings of Dalhousie University say their new study.

The study says with the Conservative government’s emphasis on prioritizing economic importance over the habitat ecology is “contrary to responsible management practices for the protection of native fishes, the act now inadvertently prioritizes habitat protection for some nonnative species—even hatchery-produced hybrids.” The study says as long as those introduced or other species are part of what the new act and regulations define as “part of a fishery,” those fish are protected, while nearby native species, not part of a fishery, have no protection.

The same economic emphasis downgrades protection for sparsely inhabitated regions (which make up most of Canada) through what the scientists call:

NO HUMANS . NO FISHERY; NO FISHERY . NO PROTECTION; NO PROTECTION . NO STEWARDSHIP

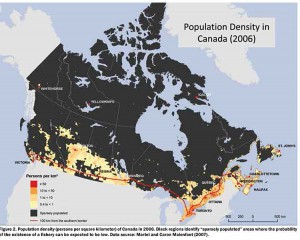

The stipulation that fish be part of, or support, a fishery will have particularly egregious consequences for species that inhabit pristine or near-pristine habitat in Canada’s vast wilderness.

Under the revised FA, fish that inhabit lakes, rivers, and streams that are not regularly visited by humans do not warrant protection. Humans are necessary to render a fish part of a fishery. No humans, no fishery, and no fish habitat protection. This can only be interpreted as meaning that the vast majority of Canada’s freshwater fishes will be deemed to not warrant habitat protection under the revised FA, even if those species are considered part of a fishery elsewhere in their range.

The changes were “politically motivated,” unsupported by scientific advice – contrary to the policy of previous governments – and are inconsistent with ecosystem-based management, fisheries biologists Post and Hutchings say.

Their comprehensive assessment, in a peer-reviewed paper titled “Gutting Canada’s Fisheries Act: No Fishery, No Fish Habitat Protection,” is published in the November edition of Fisheries, a journal of the 10,000-member American Fisheries Society.

The 2012 omnibus bill redefined fish habitat to a fishery in this clause:

No person shall carry on any work, undertaking or activity that results in serious harm to fish that are part of a commercial, recreational or Aboriginal fishery, or to fish that support such a fishery.

The two authors interpret that as meaning, that while you may be forbidden from harming the fish, there are no barriers to harming fish habitat.

… it will no longer be illegal to harmfully alter or disrupt fish habitat. The revised act only renders it illegal to cause serious harm to fish that are part of a commercial, recreational, or Aboriginal fishery or to fish that support such a fishery. “Serious harm” is defined by the act as “the death of fish or any permanent alteration to, or destruction of, fish habitat” (Fisheries Act 2013). A legal opinion prepared for the Environmental Managers Association of British Columbia concluded that serious harm does not prohibit the disruption or temporary alteration of fish habitat, concluding that many situations prohibited under the previous legislation will no longer be covered by the revised act

The new regulations proclaimed in the Canada Gazette in April 2013.

“The biggest change is that habitat protection has been removed for all species other than those that have direct economic or cultural interests, through recreational, commercial and Aboriginal fisheries,” Post says.

Before, “there used to be a blanket habitat protection for all fish species,” he says. “Now there’s a projection just for species of economic importance which, from an ecological standpoint, makes no sense.”

The study goes on to say:

The near elimination of fish habitat protection represents a clear signal that protection of habitat—the single greatest factor responsible for the decline and loss of commercial and noncommercial species on land and in water —no longer merits explicit protection under Canadian fisheries management law.

And later:

The multitude of aquatic systems that do not support a fishery, coupled with the extensive distributions of many Canadian fishes, will mean that habitat protection will not be provided for most fish species in most places.

By applying the “no humans, no fishery” criterion, the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans will have an easy time expediting applications for fish habitat destruction resulting from all manner of development. The lack of foresight inherent in the “no humans, no fishery” stipulation is also manifest by the likelihood that aquatic systems that do not support a fishery today (e.g., much of Arctic and northern Canada) might well do so in the future. But investment in future fisheries requires investment in appropriate habitat protection today. How is a fishery to develop down the road if the habitat is already gone?

Although it is well known that the Harper government muzzles scientists from speaking to the media, that apparently doesn’t mean that there isn’t “chatter” (to use the intelligence term) among fisheries scientists themselves. As the study authors report:

based on personal communications with DFO scientists and divisional managers, it appears that scientists were not consulted at all. By all accounts, DFO scientists and managers were surprised by the degree and types of changes in the revised act. According to one very highly placed science director (in a confidential communication to one of the authors), he was unaware of the March 2012 provisions in the legislation until he heard of the government’s finalized revisions on a news broadcast.

The scientists also quote earlier studies that showed the old Fisheries Act was not unduly holding up development projects.

a key reason for revising the act—a perceived need to expedite or “streamline” environmental reviews (Canada Gazette 2013)—has been shown to lack an empirical basis. There was a perception among some politicians that the act needed to be changed because it was deemed unduly obtrusive and prevented any number of activities from occurring.

The analysis by the environmental group Ecojustice showed that between 2006 and 2011, only one proposal among thousands was denied by the DFO, and only 1.6% of 1,283 convictions under the FA between 2007 and 2011 pertained to the destruction of fish habitat.

Post and Hutchings go on to say:

These scientific analyses run counter to the political discourse, which argues that environmental reviews are unduly lengthy and are bad for economic growth. In fact, review times in Canada were found to be faster, under the previous Fisheries Act, than they were in the United States. The absence of a scientific basis for statutory change in this case is a telling example of how scientific advice can constructively assist decision makers before they revise legislation.

Proponent gets to gather the data

(Riley Brandt, University of Calgary)

Under the new regulations proclaimed in April, when an individual or company applies for an “application to undertake an activity that requires authorization by the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans” …”the primary—if not sole—responsibility for providing accurate information and data rests with the applicant, rather than with DFO habitat scientists and biologists.”

The proponent of a project has to identify whether or not “fish that are part of a commercial, recreational or Aboriginal fishery,” or “fish that support such a fishery,” at the location of the proposed work, will be the responsibility of the proponent/applicant to identify.

The two scientists say there is no way to ask what scientific standards, DFO’s or others will be applied in identifying fish that support a fishery.

There are also questions about who “will determine the scientific validity and appropriateness of each proponent’s assessment.” It could be, the paper says, the proponent themselves determining the validity of their own studies because:

There does not appear to be a requirement for the DFO to undertake an on-site inspection by DFO scientific staff to verify information provided by an applicant. This change in responsibility explains the 33% reduction in DFO staff responsible for habitat protection reported by various Canadian media in 2012. This reduction in staff can only diminish the scientific integrity and scientific credibility of DFO’s assessments of applications for the authorization of activities under 35(2)(b) of the FA that will result in the destruction of fish and fish habitat.

The study goes on to say:

The regulations confirm that the revised FA will not protect any particular species of fish. Rather, protection will be provided only to “fish that are part of a commercial, recreational or Aboriginal fishery” or “fish that support such a fishery.” This means, to take one of many examples, that Largemouth Bass (Micropterus salmoides) will be protected at a particular location if, and only if, those Largemouth Bass are considered to be part of a fishery at that location. Otherwise, Largemouth Bass will not be protected.

The scientists do acknowledge that:

It can be argued that there are positive elements to the FA revisions, such as (1) statutory recognition of the importance of recreational and Aboriginal fisheries, (2) provision for the establishment of regulations to control aquatic invasive species and prohibit their import, and (3) increased penalties and fines for contravention of the act.

They then add:

But, in our opinion, the negative consequences to Canada’s aquatic ecosystems generated by the revisions to the act outweigh these benefits, none of which actually required changes to the existing habitat protection provisions of the FA.

The scientists conclude the article by saying

Being the second largest country in the world, Canada is responsible for 20% of the globe’s fresh water, one third of its boreal forests and associated aquatic environment, and the world’s longest coastline. However, this geographical wealth comes with a responsibility to be internationally respected stewards of this vast environment. Politically motivated abrogation of the country’s national and international responsibilities to protect fish and fish habitat suggests to us that Canada might no longer be up to the task.