If some travellers, perhaps about 12,000 years ago, had headed up what is now called Douglas Channel, around the north end of Hawkesbury Island they likely would have seen a glacial retreat driven by a warming planet, something very familiar to the television viewers of 2017, video of 21st century coastal Greenland, where massive glaciers are calving ice bergs into the ocean.

The history of rapid glacial retreat over several thousand years from the interior and coastal British Columbia at the end of the last Ice Age is now becoming a crucial indicator of what may happen to both Greenland and the Antarctica. Under the current ice sheets both Greenland and parts of Antarctica are mountain ranges similar to those here in British Columbia. According to new research published to today in Science, that may indicate what could happen as those ice sheets melt and how that will affect volatile climate change.

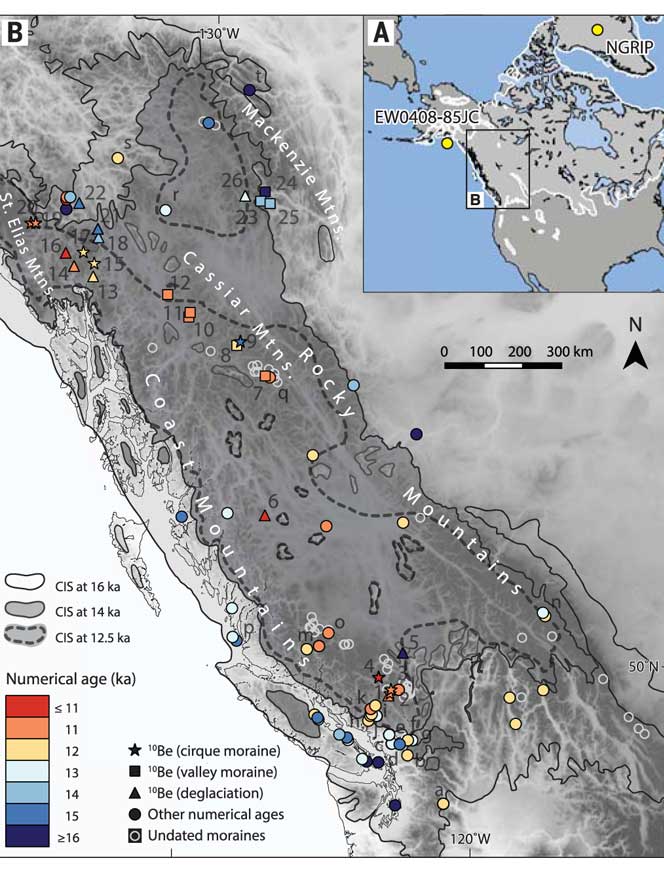

The paper written by Brian Menounos of the University of Northern British Columbia and co-authors indicates that the glacial retreat in BC was faster than previously believed, beginning about 14,000 years ago. That left some parts of coastal and western BC ice free, rather than beginning 12,500 years ago as previously estimated. The last Ice Age probably reached its maximum coverage about 20,000 years ago.

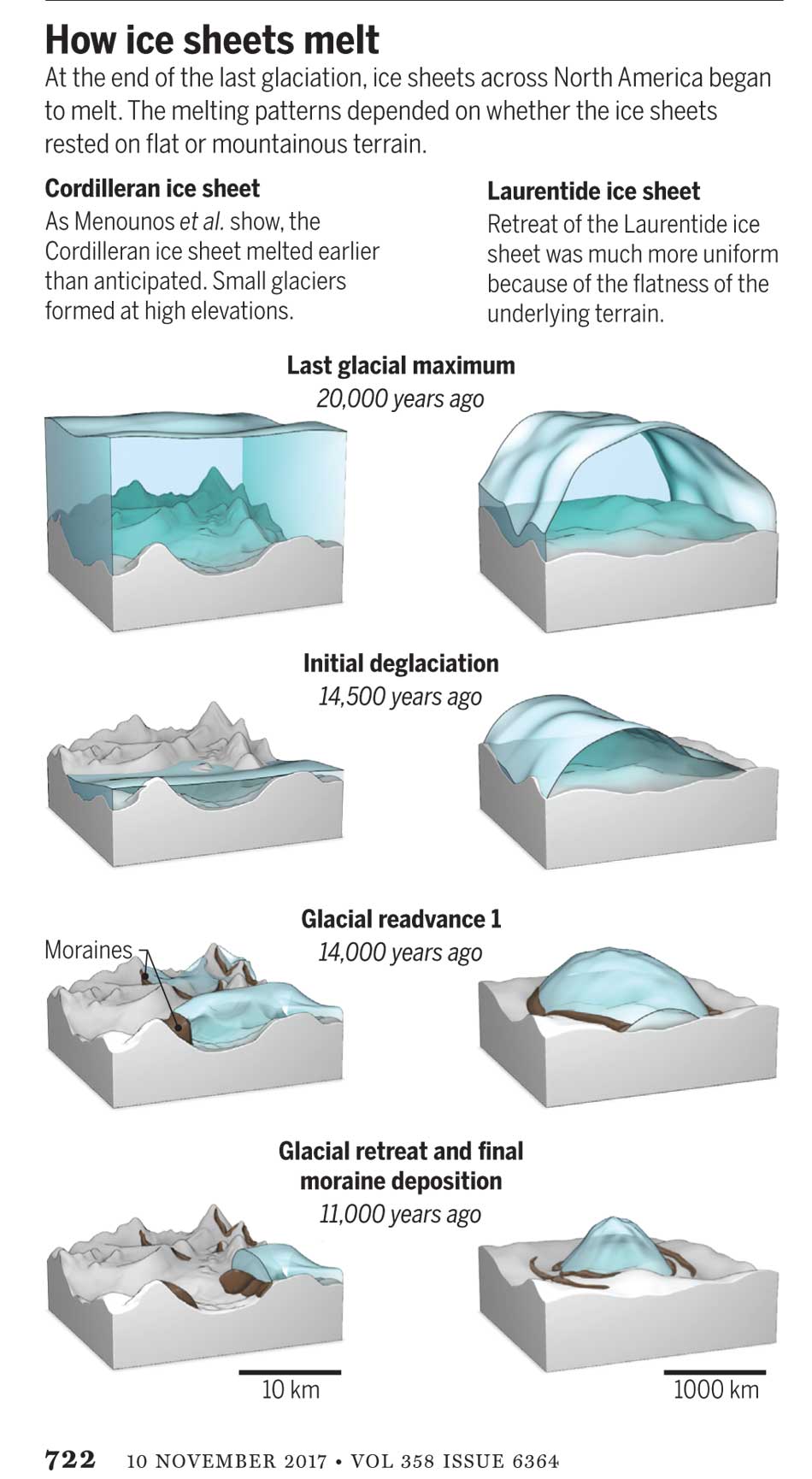

The decay of the ice sheet was complex, partly due to presence of mountainous terrain and also because Earth’s climate rapidly switched between cold and warm conditions during the end of the last Ice Age.

One of the factors that may have triggered a climate change back to colder conditions was a massive outflow of cold, fresh water from coastal British Columbia, which may have affected ocean currents.

What geologists call the Cordilleran ice sheet once covered all of present-day British Columbia, Alaska and the north Pacific United States. How the Cordilleran ice sheet responded to climate change was different from the Laurentide ice sheet which covered the flatter terrain (prairie and the Canadian Shield) of central North America. The Cordilleran ice sheet is about the same size as the current Greenland ice sheet.

“Our work builds upon a rich history of collaborative research that seeks to understand when and how quickly the Cordilleran ice sheet disappeared from Western Canada,” Menounos says. “Projected sea level rise in a warming climate represents one of the greatest threats to humans living in coastal regions. Our findings are consistent with previous modeling studies that show that abrupt warming can quickly melt ice sheets and cause rapid sea level rise.”

Menounos, the Canada Research Chair in Glacier Change, teamed up with 14 co-authors from Canada, the United States, Sweden, Switzerland and Norway to produce the paper titled Cordilleran Ice Sheet mass loss preceded climate reversals near the Pleistocene Termination.

One of the co-authors of the paper is John Clague, now a professor emeritus of Earth Science at Simon Fraser University who studied the glaciation patterns in the Kitimat valley and Terrace in the 1970s when he worked for the Geological Survey of Canada.

Earlier researchers, including Clague, relied on radiocarbon dating to establish when the ice sheets disappeared from the landscape. The problem is that radiocarbon dating may not work in higher alpine regions where fossil organic matter is rare (above the tree line).

Menounos and the researchers used surface exposure dating – a technique that measures the concentration of rare beryllium isotopes that accumulate in quartz-bearing rocks exposed to cosmic rays – to determine when rocks first emerged from beneath the ice. If the rocks are under an ice sheet that means they are not exposed to cosmic rays, and thus measuring the beryllium isotopes can indicate when the retreating ice exposed the rocks to the cosmic rays.

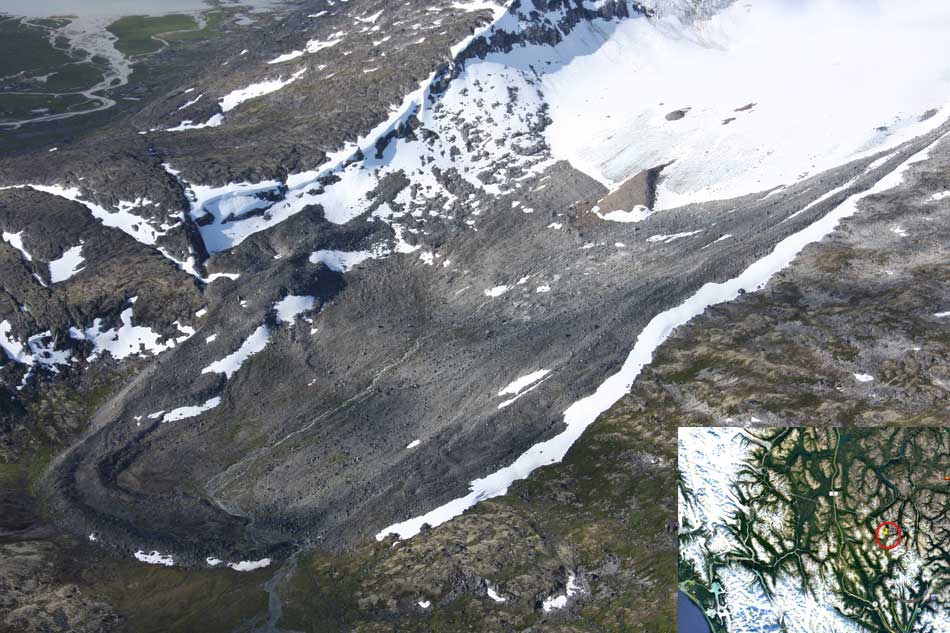

The scientists studied small “cirque moraines” found only beyond the edge of modern glaciers high in the mountains, and valley moraines.

The alpine cirque moraines could not have formed until after the Cordilleran ice sheet had retreated. Menounos and his team show that several alpine areas emerged from beneath the ice sooner than previously believed. Then once the mountain peaks emerged from the thinning ice, new, smaller glaciers grew back over the high-elevation cirques at the same time that remnants of the ice sheet “reinvigorated” in the valleys during subsequent climate reversals

Most of the work of the team was done in the interior of British Columbia, the Yukon and Northwest Territories. Menounos says that new, similar work is being done on the mountains of the coastal region which will be published when the research is complete.

At its maximum, the Cordilleran ice sheet likely extended from what is now the mainland coast across Hecate Strait to the east coast of Haida Gwaii.

Starting about 14,500 years ago, the planet entered a phase of warming, with the average temperature rising about 4 degrees Celsius over about a thousand years. The Cordilleran ice began to thin rapidly leaving what the paper calls a “labyrinth of valley glaciers,” which then allowed the alpine glaciers to re-advance.

The scientists have suggested the rapid ice loss, beginning 14,500 years ago, came relatively quickly in geological time, perhaps just 500 years. That may have then contributed to subsequent Northern Hemisphere cooling through freshwater rushing into the ocean. That melt water disrupted the overturning ocean circulation of cold and warm water. That led to a new cooling period that lasted from about 14,000 to 13,000 years ago. (Similar to the completely fictional scenario in the movie The Day After Tomorrow, where the cooling happens in days not centuries).

That same outflow could have raised then existing sea levels by two and half to three metres, Menounos says. (The overall sea level on Earth rose about 14 metres by the end of the Ice Age)

Then the climate reversed again, first briefly warming and then in a period that saw another abrupt change back to cooler conditions which geologists call the Younger Dryas, The Younger Dryas occurred beginning about 12, 900 years ago to about 11,700 years ago, when warming began again. The Dryas is named after a wildflower that grows in arctic tundras.

The study indicates that the First Peoples could not have settled the interior of what is now British Columbia prior to the Younger Dryas, but it is likely as was explored in a paper last week in Science that the First Peoples were able to come down the “kelp highway” on the coast by at least 14,000 years ago.

So what happened in Douglas Channel?

So what does the new study of glacial retreat mean for the history of Douglas Channel?

John Clague studied the Douglas Channel, the Kitimat Valley and the Terrace area in the 1970s and was one of the co-authors of the current study that provides a new timeline for the retreat of the glaciers on the British Columbia coast.

He says that the timeline from his work in the 1970s with radio carbon dating of fossilized organic material is fairly consistent with the new work by Brian Menounos of the University of Northern British Columbia using the beryllium isotope technique.

The paper, Clague says, is more of a general commentary on the last stages of the decay of the Cordilleran ice sheet.

“At the time we’re taking about in the paper, there was ice in the corridor between Kitimat and Terrace.

“What we see in detail based on the work I did ages ago, is the retreat of the glacier from the Kitimat Arm back to the north towards Terrace [in the Young Dryas ]. It occasionally stabilized and the melting ice discharged a lot of sediment into that marine embayment.

Based on his original work and the new study Clague says at the time, the mountains are beginning to become ice free but there was still ice in the major valleys such as the Skeena Valley and the corridor south of Terrace towards Kitimat.

“They’re overlapping stories.” Clague says.

“The ice sheet hadn’t completely disappeared at the time Brian is focusing on,” Clague says. “His point is that a lot of the mass of the ice sheet appeared to be thinning and through marginal retreat from Haida Gwaii and some of the islands off the mainland back toward the mainland itself. So we’re trying to put a chronology on it, as to the various steps in the glacial decay.”

The work seems to indicate that the final ice sheet retreat happened in four stages around 12,000 to 11,000 years ago. “I was interested in the detailed reconstruction of the ice front tracked north from Kitimat you see a number of periods when it stabilized long enough to build up very large deltas and braided melt water plains,” Clague says.

The first moraine is Haisla Hill in Kitimat, where the glaciers discharged large amounts of sediment into what is now Douglas Channel. The second is the hill leading to what is called Onion Flats, the third is the flat area where the Terrace Kitimat Regional Airport now is and the final stage of glacial retreat created the “terraces’ around Terrace and Thornhill.

“It’s interesting that in this area there was so much sediment discharged into the sea remarkably for the time over which the ice was retreating through the area. It had to have been a major kind of discharge point of water from the ice sheet south from Terrace towards Kitimat otherwise you wouldn’t get that huge amount of sediment deposited probably over a period of a thousand years. Then it retreated again to just north of the airport and anchored there for a while and we found evidence for a final last gasp upstream around Thornhill and that kind of near Terrace.”

“At that time some of the high elevation glaciers were re-energized and readvanced, but it probably didn’t affect the overall health of the ice sheet itself It’s such a big mass of ice that it doesn’t respond quickly to such a brief cooling so what we’ve done in many places is these glaciers actually advanced up against ‘the dead ice’ an ice sheet that was lower in elevation.”

At the times the oceans rose at the end of the Ice Age, there were “sea corridors” between Kitimat and Terrace and also in the Skeena Valley. “So you can imagine there were arms of the sea extending to Terrace from two directions almost making that area which is now part of the mainland an island.” But the region likely never did become a true island, Clague says because as the ice sheets retreated,, they were also shedding large amounts of sediment that would become land area at the same time as the earth’s crust was rebounding once it was freed from the weight of the ice sheet.