Scientists from the University of California at Davis and NOAA studying herring spawning beds in San Francisco Bay after the Costco Busan oil spill. (UC Davis)

A 53,569 gallon (202,780 litre) spill of bunker oil in San Francisco Bay in 2007 had an “unexpected lethal impact on embryonic fish,” according to scientists from the University of California at Davis and the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration who spent two years on follow-up research after the spill, looking at the effects of the spill on Pacific herring.

One significant finding from the study is that different oil compounds, for example crude or bunker oil, likely have different effects on vulnerable environments.

On November 7, 2007, the container ship Cosco Busan hit the San Francisco-Oakland Bay bridge, breaching two fuel tanks and sending the bunker oil into the bay. Television images of the accident were seen around the world.

Damage to the Cosco Busan. ( PO 3 Melissa Hauck/US Coast Guard)

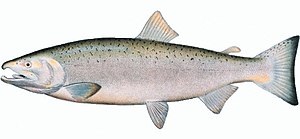

The oil spill polluted the nearby North Central Bay shoreline spawning and rearing habitat for herring, described by the study as “the largest coastal population of Pacific herring along the Continental United States.” The spill happened a month before the herring spawning season.

The herring from the estuaries of San Francisco Bay migrate in large schools up the Pacific Coast to the Bering sea, and are food for whales, other mammals, salmon and birds. After two years at sea they return to the spawning grounds.

The study also notes: “Herring are a keystone species in the pelagic food web and this population supports the last commercial finfish fishery in San Francisco Bay.” It adds: “Although visibly oiled shorelines were cleaned, some extensively, only 52% of the oil was recovered from surface waters and land or lost to evaporation. The amount of hidden or subsurface oil that may have remained near herring spawning areas is unknown.”

The study, Unexpectedly high mortality in Pacific herring embryos exposed to the 2007 Cosco Busan oil spill in San Francisco Bay, was published Monday, Dec. 26, in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The study suggests that even small oil spills can have a large impact on marine life. Gary Cherr, director of the UC Davis Bodega Marine Laboratory and lead author of the study says, “Our research represents a change in the paradigm for oil spill research and detecting oil spill effects in an urbanized estuary.”

That’s because the study builds on research following the 1989 Exxon Valdez disaster in Prince William Sound, Alaska, which released 32 million gallons (121 million litres) of crude. The Exxon Valdez spill also happened close to the herring spawning season and studies since then have shown mortality and abnormalities in the fish in Prince William Sound.

The San Francisco study shows that the bunker oil accumulated in naturally spawned herring embryos. At low tide, the oil then interacted with sunlight in the shallower regions of the estuary, killing the embryos. A control group of herring, fertilized in a laboratory and place in cages in deeper water, were protected from the combination of oil and sunlight but still showed “less severe” abnormalities.

“Based on our previous understanding of the effects of oil on embryonic fish, we didn’t think there was enough oil from the Cosco Busan spill to cause this much damage,” Cherr said. “We didn’t expect that the ultraviolet light would dramatically increase toxicity in the actual environment, as might observe in controlled laboratory experiments.”

One reason may be that crude oil, the kind spilled by the Exxon Valdez, is naturally occurring liquid petroleum. Bunker oil is a thick fuel oil distilled from crude oil and used as a fuel on ships. Bunker oil can be contaminated by other, unknown substances. In the case of the Cosco Busan, the bunker oil was relatively low in sulfur compared to some other bunker fuels but the embryos showed higher than expected levels of sulfur compounds.

Scientists from the University of California at Davis and NOAA studying herring spawning beds in San Francisco Bay after the Costco Busan oil spill. (UC Davis)

The scientists analyzed the levels of oil-based compounds in the caged herring embryos at four oiled and two-non oiled sub tidal sites, all at least one metre below the surface. Naturally spawned embryos from shallower areas were also studied.

In November, 2007, the spilled oil was visible in the areas chosen for the study. By the time the herring eggs were incubating, oil was not visible in the contaminated areas, except for some tar balls found on shore.

The researchers began the study in February 2008 . At the time, three months after the spill, the caged embryos showed non lethal heart defects, typical of exposure to oil spills. The embryos in the shallower sub tidal zones showed the same heart defects but also had “surprisingly high rates of dead tissue and mortality unrelated to the heart defects.”

“The embryos were literally falling apart with high rates of mortality,” Cherr said.

Normal herring embryos are translucent and colourless when they hatch, except for the pigment around the eye and melanophores (pigment cells) along the gut. The the brain, spinal cord and axial muscle from embryos from the oiled sites were not as clear. Those embryos had no heart beat and the skin tissue was disintegrating.

No toxicity was found in embryos in unoiled sites, even those close to major highways. The researchers concluded that the high death rates did not seem to be caused by natural or man made causes unrelated to the spill.

In 2009, when the scientists concentrated on the role of sunlight, the study showed that the embryos had death rates characterized by loss of tissue similar to the embryos from the year before, but possibly caused by undetected compounds from the oil spill.

In 2010, the scientists again looked at embryos from the oiled and unoiled sites. By that time, the hatching rates from the oiled sites were similar to the “relatively high hatching rates” for the unoiled areas. However, there was a “significant incidence” of heart problems among embryos from the oiled sites.

The scientists conclude that while the Exxon Valdez spill did show oil poisoning fish in the early stages of life, they say case wider research is needed beyond that done for in the case of the Exxon Valdez because the Cosco Busan

1. Highlights the difference in effects on fish from exposure to oil of differing composition (i.e. Crude vs bunker)

2. Shows the role of sunlight, interacting with local conditions (such as shallow water) can have significant affects on toxicity.

3. Shows the need for more study of the toxic effects of different oil compounds

4. The study has shown the “exceptional vulnerability of fish early stages to spilled oil.”

The conclusion adds “Although bunker oil typically accounts for only a small fraction of oil in ships, so spills may be small relative to those of crude oil, it may carry a potential for disproportionate impacts of in ecologically sensitive areas.”

Both Ellis Ross, Chief Counsellor of the Haisla Nation and April McLeod, president of the Kitimat Valley Naturalists expressed concern abut the findings of the study, especially with the Joint Review Hearings on the Enbridge Northern Gateway pipeline scheduled to begin a few days.

The numerous environmental critics of the Northern Gateway pipeline have pointed out that there is no way of knowing what would happen to an area like the Kitimat River, estuary and Douglas Channel is there was a bitumen spill. Enbridge has filed documents with the Joint Review Panel that include simulations of a spill. The new San Francisco study shows that any oil spill could have unforeseen effects.

Plans call for at least three new terminals to be built close to the Kitimat River estuary, not just the controversial Enbridge terminal for bitumen, but at least two for the liquified natural gas projects, KM LNG and BC LNG and in all three cases ships would normally be fueled by bunker oil.

The Kitimat estuary has been industrialized for 60 years since the building of the Rio Tinto Alcan smelter, but still has large areas teeming with fish and wildlife, so the estuary is somewhat in the middle between the heavily urbanized estuaries of San Francisco Bay and the more pristine Prince William Sound.

Ross pointed to the collapse of the oolichan in the Kitimat River as a strong indicator of potential problems. He recalls that in the early stages of the Eurocan paper mill the Haisla Nation was told there would be no effect on the oolichan, but soon after the mill began operations, the oolichan population collapsed. That is why, Ross said, the Haisla are wary of the plans and want to see more and stronger studies done on the effects of bitumen and other oil compounds in the region.

Other comments were unavailable due to the holiday. They will added as received.

Kitimat River estuary on Dec. 17, 2011, showing a Rio Tinto Alcan transmission tower. (Robin Rowland/Northwest Coast Energy News)

Kitimat River estuary on Dec. 17, 2011, showing a Rio Tinto Alcan transmission tower. (Robin Rowland/Northwest Coast Energy News)

California Fish and Wildlife Cosco Busan spill web page.

According to Wikipedia, the US National Transportation Board found that the Cosco Busan accident was caused by

- the pilot’s degraded cognitive performance from his use of prescription medications, despite his completely clean post accident drug test,

- the absence of a comprehensive pre-departure master/pilot exchange and a lack of effective communication between Pilot John Cota and Master Mao Cai Sun during the accident voyage, and

- (COSCO Busan Master) Sun’s ineffective oversight of Cota’s piloting performance and the vessel’s progress.

Other contributing factors included:

- the failure of Fleet Management Ltd. to train the COSCO Busan crewmembers (which led to such acts of gross negligence as the bow lookout eating breakfast in the galley instead of being on watch) and Fleet Management’s failure to ensure that the crew understood and complied with the company’s safety management system;

- the failure of Caltrans to maintain foghorns on the bridge which were silent despite the heavy fog;

- the failure of Vessel Traffic Safety (VTS) to alert Cota and Sun that they were headed for the tower. VTS is legally required to alert a vessel if an accident appears imminent, yet they remained silent;

- the malfunctioning radar on the COSCO Busan, which led Captains Cota and Sun to use an electronic chart for the rest of the voyage. Although Coast Guard investigators found the radar to be in working order, they did not examine it until days after the accident (allowing time for faulty equipment to be fixed, which is not uncommon after a marine accident)

- Captain Sun’s incorrect identification of symbols on the electronic chart;

- the U.S. Coast Guard’s failure to provide adequate medical oversight of Cota, in view of the medical and medication information he had reported to the Coast Guard.

NTSB report on the Cosco Busan accident (pdf)

Map showing the area of the UBC climate change study. The squares show areas used for “spatial comparison of temperature and zonation.” The circles were used for comparison. (Science)

Map showing the area of the UBC climate change study. The squares show areas used for “spatial comparison of temperature and zonation.” The circles were used for comparison. (Science)