Two related scientific papers published in the past two weeks, one on the First Peoples initial settlement of coastal North America and the second giving a probable new timeline of the retreat of the glaciers during the last Ice Age, taken together are likely confirmation of the Haisla story of how that nation first settled the Kitimat Valley.

As related in Gordon Robinson’s Tales of the Kitamaat, the First Peoples living on the coast of what is now British Columbia ventured up what is now called Douglas Channel perhaps from either Bella Bella in Heiltsuk traditional territory or from Prince Rupert in Tsimshian traditional territory.

As related in Gordon Robinson’s Tales of the Kitamaat, the First Peoples living on the coast of what is now British Columbia ventured up what is now called Douglas Channel perhaps from either Bella Bella in Heiltsuk traditional territory or from Prince Rupert in Tsimshian traditional territory.

The young men on the expedition up the Kitimat Arm spotted what they thought was a huge monster kilometres ahead with a large mouth that was constantly opening and closing. The sight was so terrifying that the men fled back to their homes and dubbed the Kitimat Arm as a place of a monster.

Later a man named Hunclee-qualas accidentally killed his wife and had to flee from the vengeance of his father-in-law. Knowing he had to find a place where no one could find him, he ventured further up the Kitimat Arm. There he discovered that the “monster” was nothing more than seabirds, probably seagulls, perhaps feasting on a spring oolichan run.

He settled along the shore of what is now the Kitimat River and found a land of plenty, with fish, seals, game as well as berries and other natural products of the land. Eventually he invited others to join him, which began the Haisla Nation and he became their first chief.

Let’s examine the new evidence so far.

- Settlement along the coastal “kelp highway” between 18,000 and 16,000 years ago, followed by a warm spell 14,500 years ago

It’s now fairly certain that the First Peoples first began to settle along the coast by following the “kelp highway” perhaps as early as 18,000 years ago and certainly by 14,000 years ago. Haida Gwaii was ice free, except for some mountain glaciation as early as 16,500 years ago. At about 14,500 years ago there was a warming spell which forced the glaciers to retreat, brought higher sea levels and the arctic like tundra ecosystem would have been replaced, at least for a time, by forests. There is the discovery of a Heiltsuk settlement dated to 14,000 years ago. At that time almost all of the coast would have been free of glacial ice but there were still glaciers in the fjords, including the Kitimat Arm which would mean there could be no permanent settlement in the “inland coast” and the interior.

- The cooling period from 14,000 to 11,700 years ago confines settlement to the coast

The cooling periods (with occasional warmer times) from about 14,000 years ago to about 11,700 years ago meant that settlement would largely have been confined to the coast for about two and half millennia. The culture of the coastal First Peoples would have been well established by the time the glaciers began the final retreat.

(Remember that it is just 2,000 years from our time in 2017 back to the height of the Roman Empire under Augustus Caesar).

It is likely that the cooling periods also meant that some descendants of initial settlers likely headed south for relatively warmer climates. Rising sea levels meant that the initial settlement villages would likely have been abandoned for higher ground.

- A second period of rapid warming 11,700 years ago which opens up the interior fjords and valleys

At the end of what geologists call the Younger Dryas period, about 11,500 years ago, the climate warmed, the glaciers retreated further, in the case of Kitimat, first to what is now called Haisla Hill, then to Onion Flats and finally to Terrace.

- Large glacial sediment river deltas filled with fresh melt water from retreating ice

The most important confirmation of the story of Hunclee-qualas’s exile is the account of the monster, the birds and the oolichan run.

The new scientific evidence, combined with earlier studies, points to the fact that the glacial melt water carried with it huge amounts of glacial sediment that created vast river deltas in coastal regions of the Northern Hemisphere.

That means around 10,000 years ago, when the Kitimat Valley was ice free and the new forest ecosystem was spreading up the valley, the Kitimat River estuary was likely to have been much larger than today. It could have been a vast delta, which would have quickly been repopulated with fish, including salmon and oolichan. That rich delta ecosystem could have supported a much larger population of seabirds than the smaller estuary in recent recorded history.

The story of the monster those first travelers saw far off is highly plausible. Even today in huge, rich deltas elsewhere in the world, seeing hundreds of thousands of birds in flight over a wetland is fairly common. (For a description of what a Kitimat River delta may have been like thousands of years ago, see KCET’s story on the Sacramento-San Joaquin Bay Delta and what that delta was like 6,000 years ago)

The First Peoples had had well established communities for up to four thousand years before the Kitimat Valley’s metres of thick ice had melted away. For the first period, while the ecosystem regenerated, for the people of the coast coming up Douglas Channel to the valley would not have been worth it, there would be little to find in terms of fish, game or forest resources.

- The change from tundra to a rich forest environment

Eventually as the forest regenerated, the streams filled with salmon and oolichan; the bird population including gulls, geese and eagles, found a new feeding ground; bears, deer and other animals arrived. The Kitimat region would have been an attractive place to explore and hunt. It may be the monster story did keep people away until Hunclee-qualas had to find a place to hide and discovered a new home just at a time that might be called an ecological optimum with new forests stretching back along the valley to what is now Terrace.

- The river delta shrinks back to the current estuary

If a vast Kitimat River delta did stretch further down the Channel than it does in 2017, it likely shrank back in the subsequent millennia. Eventually the mass of glacial sediment that came downstream after the retreat of the ice would diminish, but not stop entirely. The estuary is still rebuilt from sediments washed downstream but that sediment doesn’t match other rich deltas elsewhere such as the Nile in Egypt. With that regeneration of the delta slower and smaller than in the first centuries of Haisla settlement, at the same time the land surface rebounded from the weight of the ice, perhaps creating the Kildala neighborhood. The ocean level rose, drowning and eroding part of the old delta, creating the estuary we know today.

As the authors of the paper on the First Peoples’ settlement note, most of the archaeological evidence of early coastal settlement is now likely many metres below the surface of the ocean but deep ocean exploration may uncover that evidence. As the scientific team on the second paper say, they are now working on detailed studies of the glacial retreat from the coastal mountain region which may, when the studies are complete, change the timeline

While waiting for further evidence from archaeology and geology it is safe to say that the stories of the monster and later Hunclee-qualas’s discovery of the Haisla homeland are even more compelling than when Gordon Robinson wrote Tales of the Kitamaat. We can now speculate that there was once, stretching from Haisla Hill far down the Channel, a vast, varied rich, river estuarine delta that supported hundreds of thousands of seabirds, which if they took the wing in unison, would have made those unwary travelers millennia ago, really think that there was a giant monster waiting to devour them at the head of the Kitimat Arm.

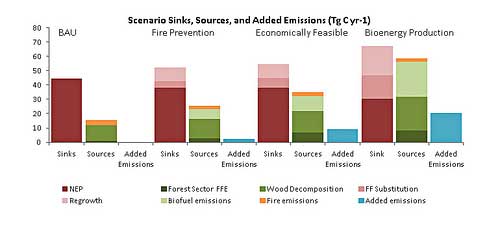

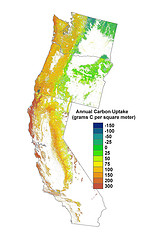

For four years, the Oregon State study examined 80 forest types in 19 ecological regions in the three states, ranging from temperate rainforests to semi-arid woodlands. It included both private and public lands and different forest management practices.

For four years, the Oregon State study examined 80 forest types in 19 ecological regions in the three states, ranging from temperate rainforests to semi-arid woodlands. It included both private and public lands and different forest management practices.