Northwest Coast Energy News will use selected testimony from the Joint Review hearings, where that testimony can easily turned into a web post. Testimony referring to documents, diagrams or photographs will usually not be posted if such references are required. Depending on workload, testimony may be posted sometime after it originally occurred. Posting will be on the sole editorial judgment of the editor.

By Murray Minchin

I’ve been here since I was about four years old. I’m 52-ish now so I’ve been here for 48 years. I’ve left for school, went to college. I would go travelling and then — but I always came back. Like the power of this place always drew me back.

I’ve hiked almost every mountain in the region and I’ve hiked the rivers and particularly the little tiny side creeks that run down the mountain sides here. And as you drive in there’s a little tiny creek that runs into the marina at Minette Bay.

So if you’re ever back, there’s a hint to you, there’s about 12 waterfalls on that little tiny inconsequential creek that nobody ever even thinks about. I suggest you take a walk up there because it’s incredibly beautiful. This area is loaded with places like that, that are singularly beautiful on a really small scale when you step back from the whole and you go into these little tiny spots. They’re just amazing.

I’ve sea kayaked quite a bit. My wife and I spent six months sea kayaking down the whole coast of British Columbia. We did two months in the winter, two months in the spring and fall and two months in the summer. So we did six months over the whole year.

It takes about two weeks when you’re out there for just the mess — the extra stuff in your head from our society and our way of life to just kind of drop away, and after about three weeks then you begin to open your eyes and you begin to feel comfortable in a place. Like you become essentially really comfortable in the environment.

When we got to Port Hardy we booked a motel room and walked in the motel room and we sat down on the floor and we started going through our gear and started talking.

It took about 15 minutes before we realized that there were chairs in the room and we could sit on them. Like we were just so in tune with being out in the bush and — like that really changes your perception of the world. You know, like you become a little more aware.

Now, like for me, when I walk into the forest here it’s like an embrace.

There’s — it’s a palpable feeling to me that I feel completely embraced and at home in this environment.

I dropped over in the Mount Madden or into the Skeena watershed into a cirque that was surrounded by waterfalls dropping into it. So I couldn’t hear anything but the waterfalls, and as I came around the lake I heard the sound of a grizzly bear just screaming his head off and I couldn’t tell where it was coming from because the sound was echoing off the rock walls.

You know, I had to hunker down under trees and then just stop and think,

okay, like take it easy, don’t do anything too fast, take your time, make the right

choice. Experiences like that sort of show you that you — our place in the environment isn’t as strong as we think we — as it is. Like the environment has a lot more drastic effect on us than we realize.

Oh, and it was a couple of decades later I was listening to the CBC radio and I heard that sound again, and evidently it was older mature cubs fighting over a kill, cause I recognized that sound right away. But when I was out there I didn’t know, I thought it was directed towards me, possibly.

My daughter was two or three years old when I began taking her into the forest. Just past here there’s the marina, and then if you take a trail past the marina, there’s a totem pole in the forest, and you take a walk past the totem pole, you follow this trail that goes along the shoreline. So she was on my hip and we were walking through the forest.

I walked off to the side and I picked a red huckleberry off the bush and then gave it to her, and she popped it in her mouth and then, like her eyes lit up and she started jumping, you know, because she started pointing and now I had to walk through the forest to every red huckleberry bush so that she could get a taste of the red huckleberries. Now that’s part of her life and that will be part of her oral history.

On part of that trip we had a couple experiences, — on our kayak trip we had some experiences- just trying to figure a way to frame this — like yesterday at Haisla we were saying that in particular with the whales, like they’re here but in the past there was a great number of them, you know.

On our kayak trip after leaving Bishop Bay we came out on to three sleeping humpback whales, which was an amazing experience for us. But as I understand now, in the past, there would have been a lot more. And I’m really — fills me with hope to hear that they’re coming back. And it’s some disconcerting to think that that could be jeopardized in any way.

Kanoona Falls. It’s just above Butedale. Like here water is everything. we got stuck there for four days in big storms near hurricane force storms and it was raining really hard. This river was in flood; it was up into the trees on either bank and it was running completely pure, like there was no sediment in it. There It wasn’t muddy. It was just a pure river running

wild. And this is what the Kitimat River must have looked like in the past, you know, running pure in flood and no sediment.

There’s so much rain here that in mid-channel — like a channel could be two or three miles wide and there’s so much rain coming off the mountains, through the rivers and streams into the ocean that the seagulls take freshwater baths at mid-channel. It makes me wonder, scientists being who they are, engineering being who they are, the Proponent trusting their advice, has made estimations on spill response and stuff with materials and saltwater.

In the winter here you’d have to go down a foot, probably, before you find saltwater and in fact we had the sea kayak 140 kilometres south from Kitimat before salted to encrust on our decks. That’s how much freshwater is out there.

So any of the Proponent’s estimations on spill response times in saltwater, which is denser of course, should be looked at or refigured because saltwater being denser would hold the product underneath the level of the freshwater on top.

Here it rains like crazy, just suggested by the moss that you can barely see in the contrasting photograph but the forest here filters the rain so that it enters

into the rivers and the rivers run clean and the salmon and the eulachon spawn in the clean river which brings the bears; the bears carry the fish into the forest, don’t eat all of the fish and then it feeds the forest when then filters the rains for the next — for the next salmon coming up.

It snows like crazy here, like I said, you guys are really lucky that you dodged one by coming here when you did. Like four-foot snowfalls are an amazing thing to you. You know, it’s not a snowfall it’s a force of nature.

If you catch a snowflake on your tongue, one of those snowflakes on your tongue you wait for it to melt, it doesn’t and you have to chew it; like they’re twice the size of a toonie, you know, and a quarter inch thick. It’s hard to imagine but it’s a force of nature when it’s snowing like that which brings concerns about access issues, obviously.

[There are] access issues, just daily access issues anywhere, particularly on to logging roads or access roads into the wilderness, there are going to be of a great concern and even more so in emergencies when equipment and materials have to be moved anywhere.

Another problem we have here in thinking about liquid petroleum product moving through this territory is the length of out winters. The average night time low is below freezing for five months of the year and for another one of those months it’s just one degree above freezing; so things can lock up and be under ice for months at a time.

If there is any slow leak — for lack of a better term — which we haven’t been able to iron out through the information request process, you know, a spill could go for weeks without being recognized, even if the weather is good enough to get a helicopter up to fly over the area. Things could be under the ice and invisible until it gets to Kitimat and somebody notices that there is a spill happening.

This is a sapling that is growing in an estuary and it tried, I mean it tried everything it had, it had branches ripped off, the prevailing winds and it struggled but eventually it just got pushed over and died because it was in the wrong place, which I think much like this proposal and this attempt to get tar sands, bitumen from Alberta to Asia and California is — it’s just in the wrong place.

So this, to me, this is in the wrong place and this is just the first such proposal that’s reached this level of inquiry or to reach the Joint Review Panel stage, it doesn’t necessarily make it the right one and that’s really important, especially considering how much — how many forces they’re being applied to use. Well, to buy different entities to approve this project.

It’s really important to remain cognisant of the fact that this is just the first

one; it doesn’t make it the right one.

Getting back to the environmental aspect of this; this is a nurse log. You can’t see it because of the contrast of the projector. But it’s a nurse log with little tiny seedlings of more hemlock trying to grow through it. The fungus is breaking down the log. And this natural system, if it’s allowed to play out, will recover.

If we give this place a chance to recover, it will; the cumulative effects of all the industry that’s been in here and the damage it’s done over time.

It’s shocking to think in 60 years you can kill a river. And that’s what’s happened here. We’ve almost done it. Like the salmon are hanging on because of the hatchery. The eulachon are almost gone.

If we give it a chance, it can recover. The humpback whales are coming back this far into the channel. Like we saw one in front of the — I don’t know if you’ve eaten at that — the restaurant here, but last year we were here and there was one feeding right outside on the beach, just off — about 100 feet off the beach.

So if we give it a chance, it will recover. And to threaten that in any way is — morally, for me, it’s just wrong. To risk so much for so little short term gain is not part of my mindset. I can’t comprehend that.

Like this spruce on Haida Gwaii; it’s on the Hecate Strait side of Haida Gwaii. You know, it’s in from the beach a little bit but, you know, with the 120 kilometre an hour, 100-whatever an hour kilometre an hour with northerly outflow winds we have around here, even a place like this would get spray from bitumen that’s coming in at high tide.

This is a tree that’s just barely hanging on, on Cape George. It’s on the southern end of Porcher Island with Hecate Strait in the background. And it’s just an example of what things have to do here when — to try and survive when the environment is so severe.

We paddled up into here on our sea kayaking trip, we came in at high tide and we were looking up at the rocks and then back into the distance and there was still nothing growing. It was just incredible to think.

So after we set up camp, I came around here and then took this photograph because where the water is, is high tide and beach logs are normally pushed up down the line along the shoreline, you know, nice and neatly tucked against the forest by the high tides.

these are just scattered all over the rocks, and that’s because the waves there are so big in the wintertime when the southeast storms come in that, I mean, like there’s nothing living for 10 feet up and, I don’t know, 70, 80 feet back because of the continual, every year storms coming in and pushing these logs and rolling them around.

Huckleberries, beach grasses, hemlock trees, anything will — if there’s any available space for something to grow, it’s going to grow. So this just speaks to the fact that the storms here are so continual and so severe that it’s a recipe for disaster.

You get waves crashing in on — so high onto a ship that the spray is getting down into the air ducts and down into the mechanics of the ship and then you’re adrift.

It’s a different — like after you — from travelling east, once you come into the Skeena Valley and you cross over that coast Range Mountains, everything is different. All your precepts from Alberta, Saskatchewan, Ontario, don’t matter here. There are severe environmental risks here beyond anything else in Canada.

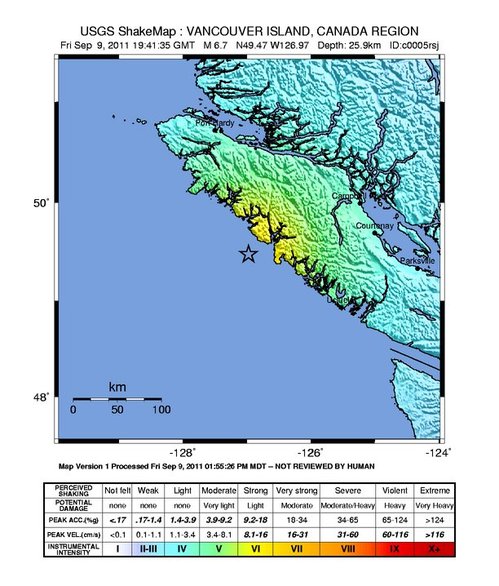

I mean, the mountains are so young. The seismicity of the area is the area is questionable because there hasn’t been that much accumulated evidence over time. So it’s just something to be aware of.

It’s a place called Cape George on Porcher Island, which is just above Kitkatla.

There is Cape George, and this is just a storm that happened to miss us, but we were stormbound there for about four days.

I ask of you that you really consider that responsibility. You know, obviously you do, but it’s important for us to know that you, that you take that responsibility really seriously because like the — in t he Federal Environmental Assessment Review Office Reference Guide, as a guide to determining whether a project is likely to cause a significant environmental effect or not, it’s quoted as saying:

The Act is clear that the project may be allowed to proceed if any likely significant adverse environmental effects can be justified in the circumstances.

So what possible circumstances are there to risk such a place and to risk so many First Nations cultures?

So what I was saying was if you give nature a chance to heal, it will heal itself, and that’s what’s happening here and that’s what the Haisla elders were telling us yesterday, that this place wants to heal itself and it can if we give it a chance.

You know, to add more risk to the cumulative damage that’s already been done here, I think, would be essentially a crime. It should be given a chance to heal.

Another thing that Mr. Ellis Ross said yesterday was, you know, much like he’s making his own history, his oral history today and in his life, like you are as Panel Members making your own history as well and your ancestors are going to speak of what decision you made and the consequences of that decision.

The International Pacific Halibut Commission is recommending drastic cuts in quotas along the west coast for the 2012 season and possibly even larger cuts for the 2013 season.

The International Pacific Halibut Commission is recommending drastic cuts in quotas along the west coast for the 2012 season and possibly even larger cuts for the 2013 season.

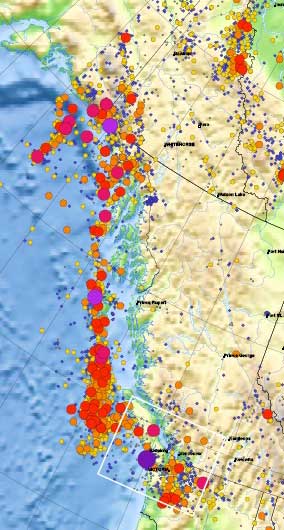

This detail of the Natural Resources Canada/ Earthquakes Canada shows the historical record of earthquakes along the northwest coast of British Columbia. The larger the circle, the greater the magnitude.

This detail of the Natural Resources Canada/ Earthquakes Canada shows the historical record of earthquakes along the northwest coast of British Columbia. The larger the circle, the greater the magnitude.