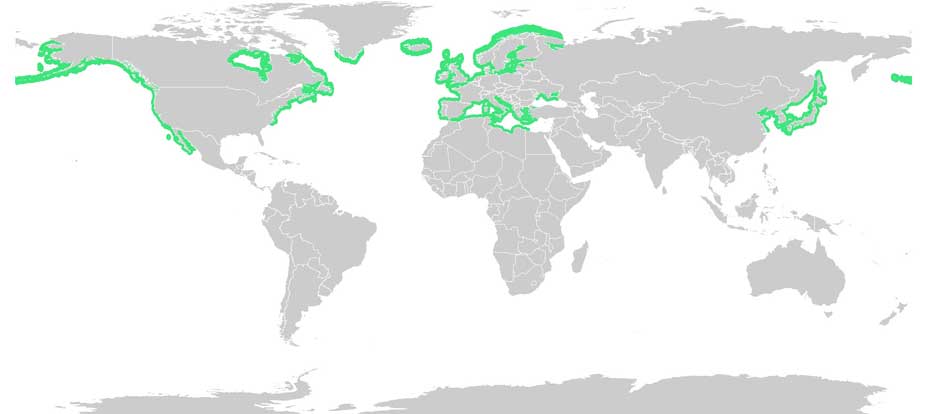

In 1999, a tropical fungus called by scientists Cryptococcus gattii unexpectedly appeared on Vancouver Island. Spores from the fungus can cause a sometimes fatal pneumonia-like illness in humans, cats, dogs and marine mammals, including porpoises and dolphins. There is one reported case of the fungus infecting a great blue heron.

Normally, the fungus is most common in Papua New Guinea, Australia and South America. Today it is also found growing in the coastal forests and shoreline areas of southern coastal British Columbia, Washington and Oregon.

A study, released today, supported by the US Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is described as tracking multiple pieces of a puzzle. It suggests that a singular event, like a natural disaster, could have been the missing piece that brought the whole picture together.

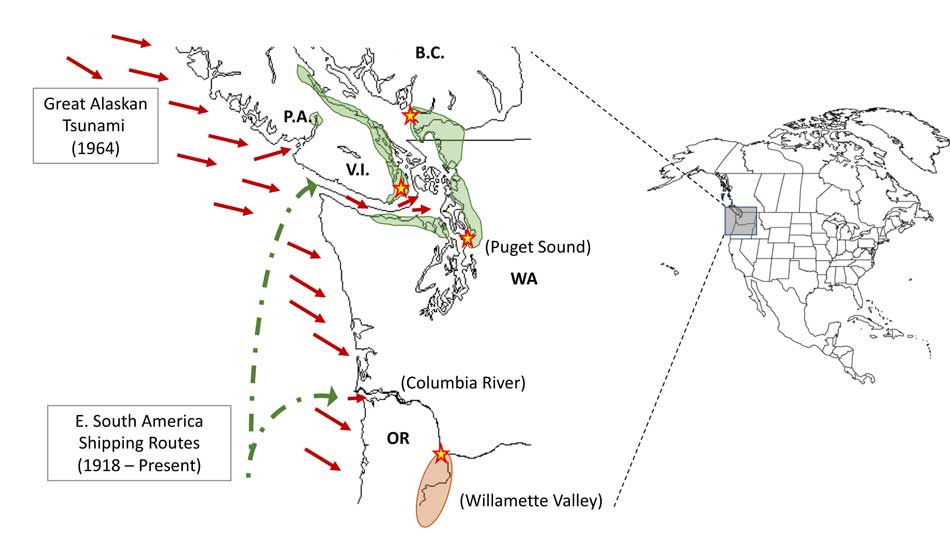

The scientists, microbiologist Arturo Casadevall, MD, PhD, Chair of Molecular Microbiology and Immunology at the Bloomberg School at Johns Hopkins University, and epidemiologist David Engelthaler, PhD, of the Translational Genomics Research Institute, Flagstaff, Arizona, suggest that a series of events brought the fungus to BC culminating in its possible spread by the tsunami unleashed by the 1964 magnitude 9.2 earthquake in Anchorage, Alaska. The scientists wrote that the tsunami idea seemed to fit the “when, where, and why” of this disease emergence.

The US CDC has tracked more than 300 C. gattii fungal infections in the Canadian and U.S. Pacific Northwest region since the first case on Vancouver Island in 1999. Prior to that time, infections with this fungus had been confined almost entirely to Papua New Guinea, Australia, and South America. The fungus typically infects people through inhalation. It can cause a pneumonia-like illness, and may also spread to the brain, causing a potentially fatal meningoencephalitis. Although the disease is fairly rare and few infected people become ill, for those who become infected, published case reports suggest an overall mortality rate of more than 10 percent.

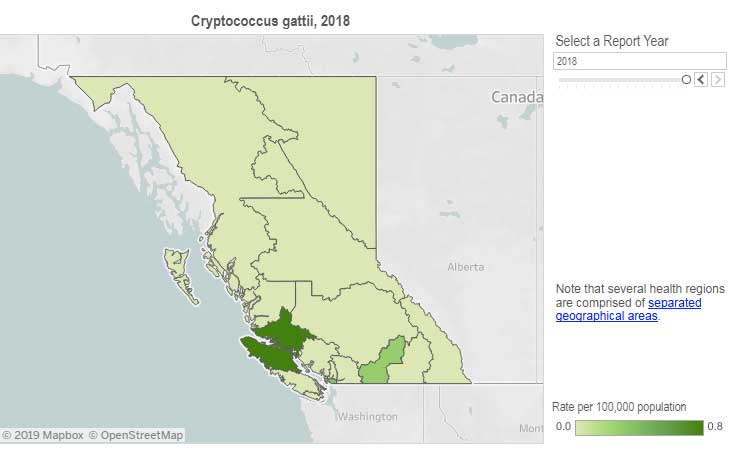

The British Columbia Centre for Disease Control (BCCDC) says Vancouver Island has one of the highest rates of infection in the world. Each year in B.C. from 10 to 25 people become sick from cryptococcosis and about 16 per cent die from the disease.

In the Northern Health region, however, only one case, in 2017, has been reported since 2009 and that was in the Northern Interior region.

The BCDC says the fungal infection can take several months to incubate after exposure. Only a few people exposed to the spores will become ill. Cryptococcus gattii is a reportable disease in British Columbia.

The new study is suggesting that the fungus first traveled in ships’ ballast tanks. After the Panama Canal opened in 1914, shipping increased significantly between Atlantic and Pacific ports.

The scientists believe that in South America, the fungus began washing from local rivers into shore waters. Then ships loaded ballast water, which research has shown is a common mode of transport for invasive species. The ballast water then spread the fungus to North American waters. Ships in those days routinely took on such ballast water in one port and simply discharged it, without treatment, in another.

How the tropical pathogen established itself in such a cool northern area was originally unclear. Theories have included global warming and the import of tropical eucalyptus trees.

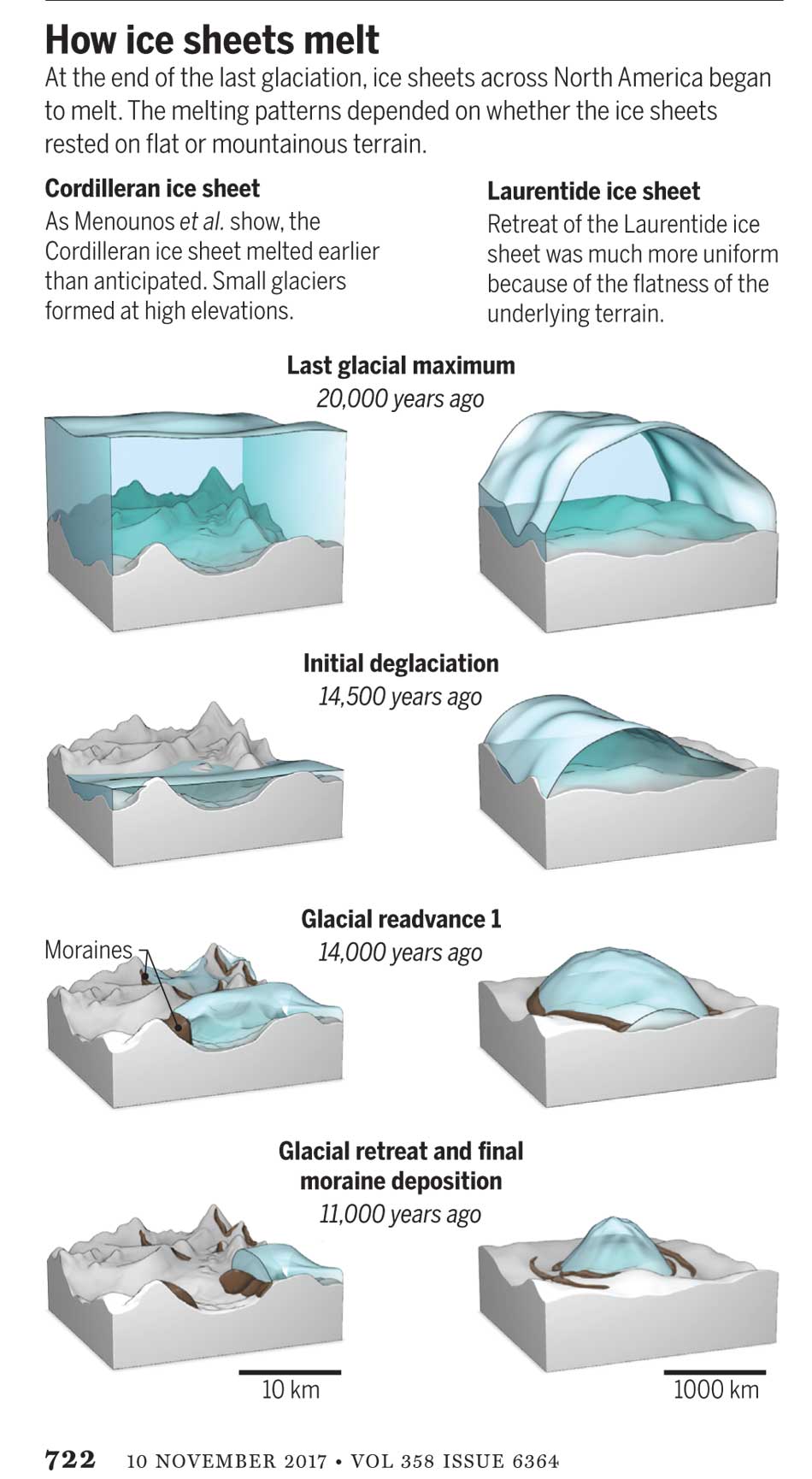

The new study proposes that once in the North Pacific the fungus went unnoticed until the 1964 earthquake brought the fungus widely ashore and into coastal forest area.

It then took several decades for the fungus to evolve in its new habitat so that it could survive and then thrive first in coastal Vancouver Island, then across the island to the Lower Mainland and down to Washington and Oregon.

Casadevall says, “The big new idea here is that tsunamis may be a significant mechanism by which pathogens spread from oceans and estuarial rivers onto land and then eventually to wildlife and humans, If this hypothesis is correct, then we may eventually see similar outbreaks of C. gattii, or similar fungi, in areas inundated by the 2004 Indonesian tsunami and 2011 Japanese tsunami.”

The Alaskan Earthquake was felt as far as 4,500 kilometres away. Effects were recorded on the Hawaiian Islands. The waves reported in nearby Shoup Bay, Alaska were 67 metres causing significant shoreline devastation. At Seward, Alaska, the tsunami wave was 9.2 metres. At Port Alberni it was 6.4 metres. North of Kitimat, at Ketchikan, the wave was just 0.6 metres and at Prince Rupert, 1.4 metres. There are no figures for Kitimat, but with no damage reported, it is likely that the wave was somewhere around a metre.

The tsunami continued south, affecting much of the coastline of western North America, even causing several deaths on the beaches of northern California.

Several hours after the earthquake, multiple waves flowed up Alberni Inlet, cresting at eight metres and striking the Port Alberni region, washing away 55 homes and damaging nearly 400 others

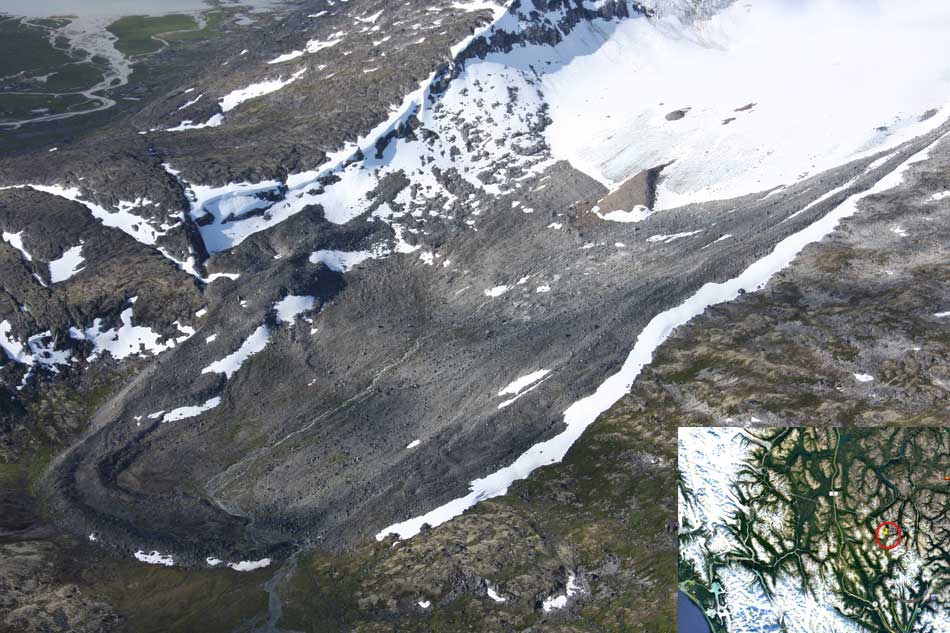

The study retrieved multiple fungus samples from the forests in the Port Alberni region. Studies show there are multiple infected sea mammals in the port’s waterways. Human and terrestrial and marine animal cases have also been reported along the western coast of Vancouver Island. The results suggest that the contamination of the Port Alberni region may be from the 1964 tsunami rather than from terrestrial dispersal from the eastern side of Vancouver Island.

The early environmental analyses in British Columbia identified that the fungus was found in soils and trees in the coastal Douglas fir forests and in coastal Western Hemlock forests bordering the coastal Douglas fir forest. While these studies were “limited in geographical space” the contaminated landscapes were also the known locations of human and animal infections. Further ecological analyses have identified higher levels of soil and tree contamination at low-lying elevations close to sea level.

The researchers now hope to continue testing their hypothesis with detailed analyses of C. gattii in soils within and outside tsunami-inundated areas of the Pacific Northwest. They then want to compare the British Columbia fungus with DNA collected from other parts of the world.–to see if the same C. gattii subtypes found in Brazil and the Pacific Northwest are more widely present in seawaters around ports.

The paper: “On the emergence of Cryptococcus gattii in the Pacific Northwest: ballast tanks, tsunamis and black swans” by David Engelthaler and Arturo Casadevall is in the journal Ecological and Evolutionary Science

BCDC defintion

Cryptococcus is a tiny (microscopic) yeast-like fungus. A species of this fungus, called Cryptococcus gattii, has been living on trees and in the soil on the east coast of Vancouver Island since at least 1999. More recently it has also been found in the Vancouver Coastal and Fraser Health regions. Infrequently, people and animals (e.g. cats, dogs, llamas, porpoises) exposed to this fungus become sick with cryptococcal disease (or cryptococcosis). Cryptococcosis can affect the lungs (pneumonia) and nervous system (meningitis) in humans. It affects people with healthy and weakened immune system. In rare cases, this disease can be fatal.

Many people will be exposed to the fungus sometime during their lives and most of these will not get sick. In people who become ill, symptoms appear many months after exposure.

Symptoms of cryptococcal disease include:

Prolonged cough (lasting weeks or months)

Shortness of breath

Headache

Vomiting

Fever

Weight loss

If symptoms occur, the disease can cause pneumonia, meningitis, nodules in the lungs or brain, or skin infection.

People are advised to see their doctor if they live in or visit an area where the fungus can be found and experience these symptoms.