Call it “the wisdom of elders.”

A new study concludes that British Columbia’s southern resident Orca pod is led by “post reproductively aged” females who help it survive during lean years.

According to the study, the older females serve as key leaders, directing younger members of the pod, and especially their own sons, to the best spots for landing tasty meals of salmon, helping their kin to survive. This leadership role takes on special significance in difficult years when salmon are harder to come by.

The researchers say the discovery offers the first evidence that a benefit of prolonged life after reproduction is that post-reproductive individuals act as repositories of ecological knowledge.

There are only three species on Earth where females go through menopause, human beings, killer whales and pilot whales.

“Menopause is one of nature’s great mysteries,” says Lauren Brent of the University of Exeter in the United Kingdom. “Our study is the first to demonstrate that the value gained from the wisdom of elders may be one reason female killer whales continue to live long after they have stopped reproducing.”

The scientists say in their paper this also provides insights into why human women continue to live long after they can no longer have children.

The study is in Current Biology “Ecological Knowledge, Leadership, and the Evolution of Menopause in Killer Whales” by Lauren J.N. Brent, Daniel W. Franks, Emma A. Foster, Kenneth C. Balcomb, Michael A. Cant and Darren P. Croft, says:

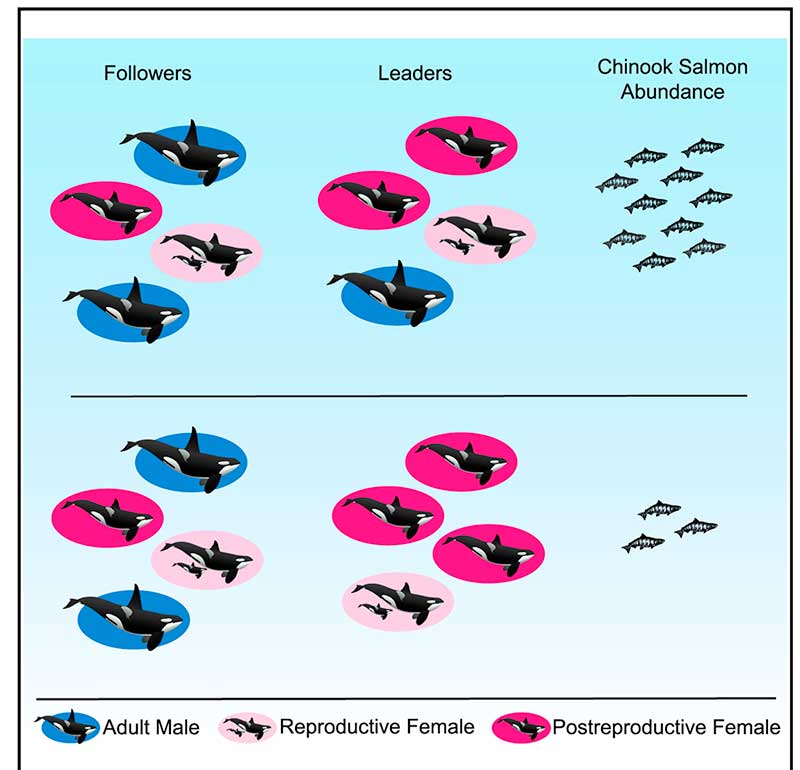

Leadership by these females is especially prominent in difficult years when salmon abundance is low.

Female killer whales typically become mothers between the ages of 12 and 40, but they can live for more than 90 years. By comparison, male Orcas rarely make it past 50.

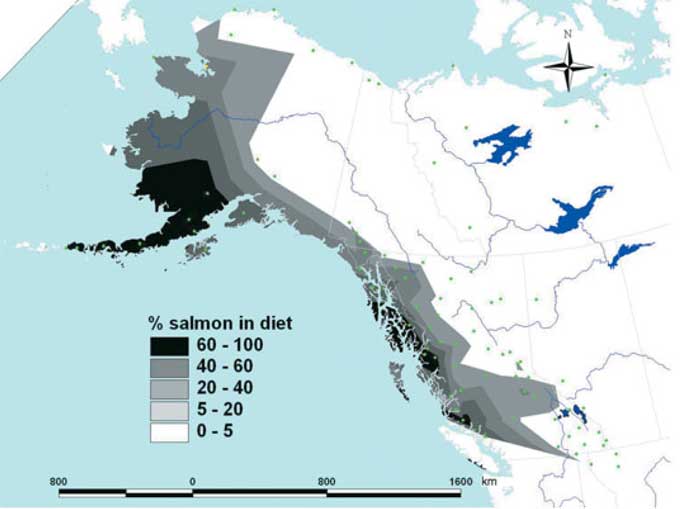

Resident pods feed mostly on Chinook salmon. Chinook make up than 90 per cent of their diet during the summer. The abundance of salmon fluctuates due to fishing by humans and weather changes such as El Nino and climate change. The study says that individual killer whales with information on where and when to find salmon provide other group members with considerable benefits.

To find out who were the leaders of the Southern Resident pod, the team analyzed 751 hours of video footage taken over 35 years of as many as 102 Southern resident killer whales in the coastal waters of British Columbia and Washington engaged in directional travel , collected during nine summer salmon migrations. The scientists also used multigenerational demographic records have been recorded for the Southern resident killer whales since 1976, allowing them to know the family relationships of the Orcas.

(David Ellifrit, Center for Whale Research)

The study found that in any given year, adult females were more likely to lead the pod’s group movement compared to adult males They concluded that Orca matriarchs over the age of 35 years “the mean age at last reproduction for Southern resident females that lived past the age of peak adult female mortality” were more likely to lead the pod “compared to reproductively aged females.”

The scientists then compared fisheries data on Chinook salmon abundance to whale behavior. It showed that “post-reproductively aged females were more likely to lead group movement in years when salmon abundance was low.”

The scientists concluded that shows that prolonged life after the reproductive years allows the “individuals act as repositories of ecological knowledge.”

In the case of Orcas, the post menopausal matriarchs “lead group movement in and around salmon foraging grounds, and this is exaggerated when salmon are in low supply and the selective pressure to locate food is at its highest.”

The researchers also found that females are more likely to lead their sons compared to their daughters.

Daniel Franks of the University of York explained: “Killer whale mothers direct more help toward sons than daughters because sons offer greater potential benefits for her to pass on her genes. Sons have higher reproductive potential and they mate outside the group, thus their offspring are born into another group and do not compete for resources within the mother’s matriline. Consistent with this, we find that males follow their mothers more closely than daughters.”

So how does the study of Orca elders apply to human beings?

“In humans, it has been suggested that menopause is simply an artefact of modern medicine and improved living conditions,” said Darren Croft of the University of Exeter. “However, mounting evidence suggests that menopause in humans is adaptive. In hunter-gatherers, one way that menopausal women help their relatives, and thus increase the transmission of their own genes, is by sharing food. Menopausal women may have also shared another key commodity – information.”

Recent studies show that living beyond the age of 60 is much more comon in hunter-gatherer cultures than previsouly believed.

So the study concludes that in humans:

In hunter-gatherers, one way that menopausal women help their relatives, and thus improve their own inclusive fitness, is by sharing food.

Menopausal women may also share another key commodity—information. Humans were preliterate for almost the entirety of our evolutionary history and information was necessarily stored in individuals. The oldest and most experienced individuals were those most likely to know where and when to find food, particularly during dangerous and infrequent conditions such as drought.

As for Orcas:

Wild resident killer whales do not have the benefits of medical care, but, similar to humans, females can live for more than 40 years after they have ceased reproducing. An individual resident killer whale’s ability to find salmon is crucial to their fitness; in years with low salmon abundance, resident killer whales are more likely to die and less likely to reproduce.

Our finding that postreproductively aged female killer whales are especially likely to lead group movement in years with low salmon abundance suggests that the ecological knowledge of elders helps explain why females of this species live long after they have stopped reproducing. Postreproductive female killer whales may provide other knowledge to their relatives. For example, postreproductive members of this socially complex species may have greater social knowledge that could help kin navigate social interactions.

In some other species, like African elephants, survival is enhanced in the presence of older female relatives, who are more capable of assessing social and predatory threats.

So the study asks “why is menopause restricted to some toothed whales and humans?”

The scientists believe that for evolution, menopause will only evolve when the benefits for the species outweigh the costs of terminating reproduction.

In humans, resident killer whales, and short-finned pilot whales, when a female usually stays in the immediate location of her family, that means that the benefits she can gain through helping her relatives, increases with age.

Among Southern resident Orcas, neither sex leaves the family pod and “females are born into groups with their mothers and older siblings.”

As the female resident Orca ages, her older relatives who die are replaced by “her own nondispersing sons and daughters.” In ancestral humans, resident killer whales and short-finned pilot whales, the benefits of the elders helping therefore increase with age, which is thought to predispose these three species to menopause

The study notes that Orcas have a number of different “ecotypes” or cultures “which differ in their prey specialization, morphology, and behavior, and which in some cases represent genetically distinct populations.” That means “that not all ecotypes are characterized by the same social structure as resident killer whales” where females leave their birth pod. The say more study is needed to find out if menopause occurs in those Orca pods and what the role of older females is in those pods. The study also did not look at the northern residents who frequently visit Douglas Channel.