Tag: humpback whale

JRP refuses to consider latest DFO findings on Humpback Whales

The Northern Gateway Joint Review Panel has refused to consider the latest findings from the Department of Fisheries and Ocean on humpback whale critical habitat on the coast of British Columbia, including areas of ocean that could be on the route of tankers carrying diluted bitumen from Kitimat.

On October 21, 2013, Fisheries and Oceans released a report called Recovery Strategy for the North Pacific Humpback Whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) in Canada. The DFO report notes that humpback whales are a species of “special concern” by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada.

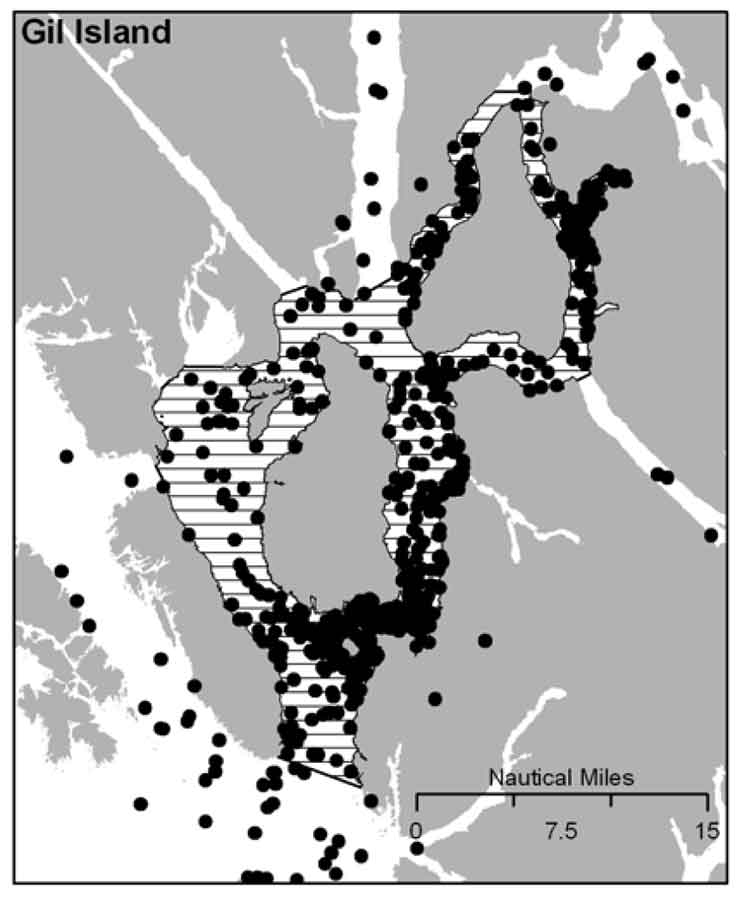

It is DFO policy to assist the humpback whale population to recover from the century of whaling that almost drove the species to extinction. The report identified four areas of “critical habitat” for humpbacks. One critical habitat zone is Gil Island at the mouth of Douglas Channel.

Last week, on November 13, Smithers based environmental activist Josette Weir filed a notice of motion with the JRP requesting that the panel consider the DFO report as late evidence.

Weir acknowledged that the JRP proceedings closed on June 24, after final arguments in Terrace, but she noted that rules allow the Board to override the final closure. She argued that the humpback report fell within the JRP’s mandate since the DFO report is “is likely to assist the Panel.”

Weir noted in her motion that there was insufficient information before the JRP that would identify critical humpback habitat.

She argued:

Three of the four critical known habitats are on the proposed tanker routes, and the Recovery Strategy acknowledges that other areas have not been identified. Without such information, it is impossible to assess the potential effects of the marine transport of bitumen on this endangered species.Activities likely to destroy or degrade critical habitat include vessel traffic, toxic spills, overfishing, seismic exploration, sonar and pile driving (i.e., activities that cause acoustic disturbance at levels that may affect foraging or communication, or result in the displacement of whales).

The report clearly identifies vessel traffic and toxic spills, which are associated with the Project as potential causes for destruction or degradation of the Humpback Whales’ critical habitat.

Weir went on to argue that the JRP had “insufficient information to develop relevant protection measures” because the humpback studies are ongoing, “meaning their results will not be available before decision.”

The Panel must consider this significant risk to an endangered listed species for which no meaningful protection measure can be offered against the risks associated with the Project.

Weir also noted that “No similar submission has been made by others, but I cannot predict if others will not see fit to do so.”

The JRP didn’t take long to reject Weir’s request, replying the next day, November 14.

In its response, the JRP cited the amended Joint Review Panel Agreement, signed after the passage of of the Jobs, Growth and Long-term Prosperity Act, the Omnibus Bill C-38, that “provides that the Panel’s recommendation report is to be submitted to the Minister of Natural Resources by 31 December 2013.”

The JRP then told Weir it didn’t have jurisdiction over endangered species (even if those species inhabit the tanker route) saying:

The Panel notes that the Recovery Strategy has been released in accordance with the provisions of the Species At Risk Act, as part of a legislative scheme that operates independently of this joint review process.

It goes on to say: “In this case, the Panel also notes that the Recovery Strategy was not authored by or for Ms. Wier.”

The executive summary of the DFO report noted:

Critical habitat for Humpback Whales in B.C. has been identified to the extent possible, based on the best available information. At present, there is insufficient information to identify other areas of critical habitat or to provide further details on the features and attributes present within the boundaries of identified critical habitat. Activities likely to destroy or degrade critical habitat include vessel traffic, toxic spills, overfishing, seismic exploration, sonar and pile driving (i.e., activities that cause acoustic disturbance at levels that may affect foraging or

communication, or result in the displacement of whales). A schedule of studies has been included to address uncertainties and provide further details on the critical habitat feature(s), as well as identify additional areas of critical habitat. It is anticipated that results from these studies will also assist in development of relevant protection measures for the critical habitat feature(s).

In the part of the report on the danger of toxic spills to humpbacks, the DFO report mentions that sinking of the BC ferry Queen of the North:

Toxic spills have occurred impacting marine habitat along the B.C. coast. For example, the Nestucca oil spill (1988) resulted in 875 tonnes of oil spilled in Gray’s Harbor, Washington. Oil slicks from this spill drifted into Canadian waters, including Humpback Whale habitat. In 2006, a tanker ruptured in Howe Sound, B.C. spilling approximately 50 tonnes of bunker fuel into coastal waters. In 2007, a barge carrying vehicles and forestry equipment sank near the Robson Bight-Michael Bigg Ecological Reserve within the critical habitat for Northern Resident Killer Whales, spilling an estimated 200 litres of fuel. The barge and equipment (including a 10,000L

diesel tank) were recovered without incident. When the Queen of the North sank on March 22, 2006, with 225,000 L of diesel fuel, 15,000 L of light oil, 3,200 L of hydraulic fluid, and 3,200 of stern tube oil, it did so on the tanker route to Kitimat, which is currently the subject of a pipeline and port proposal and within the current boundaries of Humpback Whale critical habitat

The DFO report also takes a crtical look at vessel strikes

In B.C. waters, Humpback Whales are the most common species of cetacean struck by vessels, as reported to the Marine Mammal Response Network. Between 2001 and 2008, there were 21 reports of vessel strikes involving Humpback Whales. Of these, 15 were witnessed collision events while the remaining 6 were of live individuals documented with fresh injuries consistent with recent blunt force trauma or propeller lacerations from a vessel strike.

Overall, vessel strikes can cause injuries ranging from scarring to direct mortality of individual whales. Some stranded Humpback Whales that showed no obvious external trauma, have been shown from necropsy to have internal injuries consistent with vessel strikes… It is unknown how many whales have died as a result of vessel strikes in B.C. waters. To date, only one reported dead Humpback Whale presented with evidence consistent with blunt force trauma and lacerations resulting from a vessel strike…

There are no confirmed reports of Humpback Whale collisions in B.C. waters attributed to shipping, cruise ship or ferry traffic. However, larger ships are far less likely to detect the physical impact of a collision than smaller vessels, and this could account for the lack of reported strikes. Collisions with large vessels may be more common than reported, especially in areas where larger vessel traffic is concentrated.

Despite the fact that collisions may only affect a small proportion of the overall Humpback Whale population, vessel strikes may be a cause for concern for some local and seasonal areas of high ship traffic.. In B.C., areas of high probability of humpback-vessel interaction include Johnstone Strait off northeast Vancouver Island, Juan de Fuca Strait off southwest Vancouver Island, Dixon Entrance and the “Inside Passage” off the northern B.C. mainland which include portions of two of the identified critical habitat areas..

The JRP also said

As the Panel has mentioned previously during the hearing, the later in the joint review process that new evidence is sought to be filed the greater the likelihood of the prejudice to parties. The Panel is of the view that permitting the Recovery Strategy to be filed at this late stage in the hearing process would be prejudicial to the joint review process.

Weir’s submission to the JRP did not mention an academic study published on September 11, 2013, that also identified Gil Island as critical humpback habitat.

RELATED:

“Conservatives’ hatred for science intentional part of their environmental policy,” Cullen says

DOCUMENTS:

DFO report on Humpback Recovery strategy (PDF)

Josette Weir notice of motion on Humpback Whales (PDF)

Panel Commission Ruling on Humpback Whales (PDF)

As pods recover from whaling, more whales come back to Douglas Channel, researcher believes

Whales are coming back to Douglas Channel.

In 2013, many Kitimat residents with long experience on the water have reported and are still reporting more sightings of both orcas and humpback whales.

Add to this a recently published scientific study that shows the number of humpbacks at the mouth of the channel near Gil Island has doubled in the past decade, with the study saying there were 137 identifiable whales in 2011.

So why are the whales returning? Chris Picard, Science Director for the Gitga’at First Nation and one of the co-authors of the study believes that answer is simple. There are, so far, three species of whales seen in the area, humpbacks, orcas and fin whales. It is only now, Picard believes, that the humpback and fin whale populations are recovering from a century of whaling.

The study estimates there were once about 15,000 humpback whales in the North Pacific when whalers began hunting the animals. That number was down to 1,400 when whale hunting was stopped in Canada in 1966.

As whale numbers increase, they are searching for the rich food sources found in the Channel, both at the mouth around near Gil Island where the study took place and as far north as the Kildala Arm and Clio Bay.

“One of the things the humpbacks like to do when they are on our coast or the Alaskan coast and that is they feed,” Picard said, “So they are really targeting areas that there is a high density of their preferred prey, krill or herring or other schooling fish, sardines in some years.”

So far the study has concentrated in Gitga’at traditional territory around the mouth of Douglas Channel near Gil Island. Picard says increasing the study area to include more of Douglas Channel is a good idea, but would require more resources than are currently available. “We’d like to continue with the study consistent with the work that we have been doing. Considering what we’re seeing in the local Douglas Channel area, Wright Sound, Gil Island, it can be very worthwhile.

“We are going to continue with our current study which involve getting to know how many humpbacks are using the area and continue with the study that we just published to see if numbers continue to increase or to see whether or if they do start to stabilize at some number,” Picard said. “With more and more proposals for increased shipping, we get to see any changes with humpback numbers that may be linked to increased shipping. We’ll continue to monitor the humpback population; not just their numbers but also their distribution in the area. We’ll continue to monitor that, again in relation to the various shipping proposals and activities that are proposed.”

It was during that study on humpbacks that the researchers from the Gitga’at Nation and the Cetacean Lab noticed the appearance of fin whales, another species that had been hit hard by whaling. (“We’ve worked very closely with the Cetacean Lab group and frankly without their help we would never have published any of this work because their data certainly was instrumental in getting the overall data set that made possible a publishable study,” Picard said.)

“We have observed is that fin whales have increased in their abundance in the area quite a bit, “ Picard said. “I can remember when we first started doing surveys, there were not too many. We’ve gone from seeing a couple over the course of an entire year. Now when we do our marine mammal surveys in the area the fin whales you pretty much see in every survey and in more and more numbers. So it’s quite encouraging to see that fin whales are becoming more abundent in the area. They were also hunted, so if you factor in the days of commercial whaling operations, that of course has stopped, so its encouraging to see that their numbers are coming back too.

The fin whales tend to be found in many of the same areas at the humpack whales are using, Caamaño Sound, Campania Sound and areas south of Gil Island. “we’ve also seen them more in the interior waters like Squally Channel, Wright Sound, Whale Channel, similar to the areas where we see the humpbacks.

“We haven’t done the same level of detailed analysis on the fin whale distribution as we have with the humpback, so it’s just my overall impression that they’re using similar habitats.

“It’s unique for fin whales to be using these more confined waters. It is my understanding that they are more of an open water species. I think that makes the area fairly unique,” he said.

Picard added it would be interesting to do a historic study to see how many fin whales were taken by whalers in the previous decades, especially in Caamaño Sound, Squally Channel and Wright Sound.

“The fact that we saw so many humpbacks relative to the size of the area, which is pretty small relative to the whole coast, so there must be a high abundance of food in the area,” Picard said.

“I’d like to get a better understanding of what is really driving the food abundance in the area. What is the oceanography in the area, what are the currents, what is driving that high area of biological activity that the whales seeming to be homing in on.”

That means, Picard believes, that there could be krill and juvenile herring schooling in the upper Douglas Channel and that is what is attracting the whales.

One of the next steps, Picard said, is to study social interaction among whales. “We do take identification photographs, so we get a sense of who’s hanging out with who; who is bringing their calves into the area to introduce them into what seems to be very good whale habitat,” Picard.

So one aim of a future study would be to se what role social interactions play in the increased whale sightings in the Douglas Channel. He also wants to know what role are the potential negative impacts on that whale social interaction comes noise impacts, or being struck by ships, and the potential environmental affects of oil spills. “So do these social interactions decrease as the impacts increase, does that mean there are going to be fewer whales that come into this area? Those are some of the questions we want to address.”

DFO report to JRP says Northern Gateway pipeline will cross “high-risk” streams but releases only two examples on Kitimat watershed

A Department of Fisheries and Oceans report filed Wednesday, June 6, 2012, with Joint Review Panel says the department has identified streams on the Northern Gateway Pipeline route that Enbridge identified as “low risk” but which DFO considers “high risk.” However, in the filing, DFO says it can’t release a comprehensive list of the high risk streams, preferring instead to give two examples on the Kitimat River watershed.

The DFO report comes at a time when the Conservative government is about to pass Bill C-38, which will severely cut back DFO’s monitoring of the majority of streams. It appears that the anonymous DFO officials who wrote the report acknowledge that they may soon have much less monitoring power because the report says:

Under the current regulatory regime, DFO will ensure that prior to any regulatory approvals, the appropriate mitigation measures to protect fish and fish habitat will be based on the final risk assessment rating that will be determined by DFO.

Note the phrase “under the current regulatory regime.”

The report also identifies possible threats to humpback whales from tanker traffic.

In the report, DFO notes that Northern Gateway’s “risk management framework” is based on DFO’s own Habitat Risk Management Framework, and DFO, notes “the approach appears to be suitable for most pipeline crossings.”

However, DFO further remarks that it has identified

some examples where crossings of important anadromous fish habitat have received a lower risk rating using Northern Gateway’s framework than DFO would have assigned. In addition, DFO has identified some instances where the proposed crossing method could be reconsidered to better reflect the risk rating.

In bureaucratic language, the Department says “DFO reviews impacts to fish and fish habitat and proposed mitigation measures through the lens of its legislative and policy framework” again a strong hint that the legislative and policy framework is about to change.

It goes on to say:

The appropriate approach to managing risks to fish and fish habitat is based on the risk categorization. For example, where high risks are anticipated DFO may prefer that the Proponent use a method that avoids or reduces the risk such as directional drilling beneath a watercourse to install the pipeline. If low risks are anticipated other methods such as open-cut trenching across the watercourse may be appropriate.

While DFO is “generally satisfied” with Northern Gateway’s proposed approach, it says “DFO has identified some crossings where we may categorize the risk higher than Northern Gateway’s assessment.”

DFO then gives Enbridge the benefit of the doubt because:

Northern Gateway continues to refine the pipeline route and we anticipate that assessment of risk will be an iterative process and, if the project is approved and moves to the regulatory permitting phase, DFO will continue to work with Northern Gateway to determine the appropriate method and mitigation for each watercourse crossing. In DFO’s view, Northern Gateway’s approach is flexible enough to be updated if new information becomes available.

DFO then says it

has not conducted a complete review of all proposed crossings, we are unable to submit a comprehensive list as requested; however, this work will continue and, should the project be approved, our review will continue into the regulatory permitting phase. While there may be differences in opinion regarding the risk categorization for some proposed watercourse crossings, DFO will continue to work with Northern Gateway to determine the appropriate risk rating and level of mitigation required.

Here is where DFO points to current, not future policy, when it says:

DFO is of the view that the risk posed by the project to fish and fish habitat can be managed through appropriate mitigation and compensation measures. Under the current regulatory regime, DFO will ensure that prior to any regulatory approvals, the appropriate mitigation measures to protect fish and fish habitat will be based on the final risk assessment rating that will be determined by DFO.

The report then gives two examples of high risk streams both in the Kitimat River watershed

Example 1) Tributary to the Kitimat River, KP 1158.4 (Rev R), Site 1269

Northern Gateway Rating: RMF: Low Risk

DFO Rating: RMF: Medium to High Risk

Rationale: This is a coastal coho salmon spawning stream that is quite short in length. It has several historic culverts in poor repair which are already impacting the reported run of approximately 100 spawning salmon. Works can be completed in the dry as this stream dries up during the summer. DFO is of the opinion that the risk rating is higher than that proposed by Northern Gateway due to the sensitivity of incubating eggs and juveniles of coho salmon to sediment and the importance of riparian vegetation for this type of habitat.

Example 2) Tributary to the Kitimat River, KP 1111.795 (Rev R), Site 1207

Northern Gateway Rating: RMF: Medium Low Risk

DFO Rating: RMF: Medium to High Risk

Rationale: In DFO’s view the risk rating for this watercourse is higher than that proposed by Northern Gateway because this stream is high value off-river rearing habitat for juvenile salmon such as coho salmon. This type of fish habitat is vulnerable to effects of sedimentation and loss of riparian vegetation.

Humpback Whales

The Joint Review Panel also asked DFO for a comment on the status of the humpback whale, especially in the shipping area in the Confined Channel Assessment Area Between Wright Sound and Caamaño Sound.

DFO responds

Four areas of critical habitat were proposed for humpback whales in coastal British Columbia in the Draft Recovery Strategy released in 2010, including the Confined Channel Assessment Area from Wright Sound to Caamaño Sound. However, humpback whales have recently been re-assessed by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) and were redesignated ‘Special Concern’ but remain ‘Threatened’ under the Species at Risk Act (SARA). A draft recovery strategy for the humpback whale has been prepared.

It is unclear if humpback whales are still protected as a Schedule 1 status species under the SARA and whether a recovery strategy has been finalized.

Fisheries and Oceans Canada Response to the JRPs IR Request (pdf)