Analysis (Long Read)

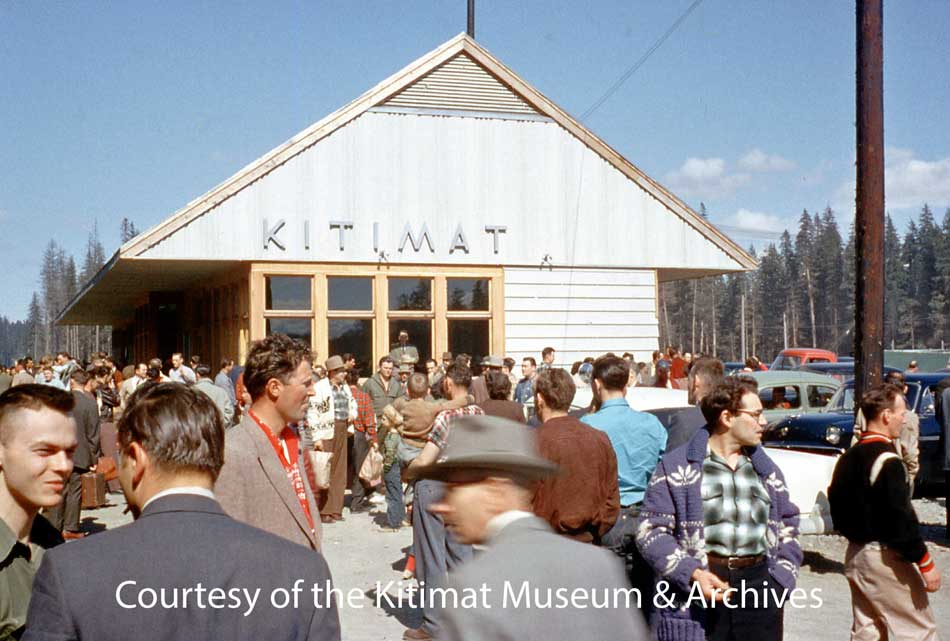

A crowd gathers at the Kitimat CN Station sometime in 1955. This picture may be of the station opening since the windows and trim are unpainted. (Walter Turkenburg/Kitimat Museum & Archives. ) See Note 1.

UPDATE: There will be a public meeting to discuss the future of the station in Kitimat on Thursday, April 11, 2019 at Riverlodge, in the Activity Room, at 7:30 pm.

March 12: This story has been updated to clarify that Kitimat Heritage has not yet discussed municipal, provincial or federal heritage status with CN. Also more information about CN telegraph communications has been added.

Kitimat Heritage and supporters in the community are campaigning to save the town’s old Canadian National Railway Station. Kitimat Heritage wants to preserve the station because it is symbolic of the earliest days of the townsite when Kitimat was first being built and celebrated as the 1950s “town of the future.”

District of Kitimat Council voted Monday February 25 to send a letter of support to CN and to take other appropriate measures to support an effort to save the old CN Railway Station in the Service Centre.

Retiring Member of Parliament Nathan Cullen (NDP Bulkley Valley) is also working at the federal level to get help to preserve the station. The provincial MLA Ellis Ross (Liberal Skeena) has promised he will work at the provincial level.

Local historian Walter Thorne and Executive Director of the Kitimat Museum & Archives Louise Avery presented a package to council that gave the history of the station and the current state of negotiations with CN. (Disclosure I am chair of the museum board but not directly involved in the campaign. The opinions in this article are strictly my own and may not reflect the views of Kitimat Heritage or the museum)

There have been two architectural assessments of the railway station. The first by John Goritsas on behalf of the Kitimat Museum & Archives in 1992 and this year on behalf of Kitimat Heritage by Prince Rupert architect Alora Griffin.

While the station overall is in “desperate condition” it appears from both assessments that the core of the station is, as far as can be determined, structurally sound.

The station, built in 1955, has been in poor repair for years. According to Kitimat Heritage CN has said it sees no other clear alternative than to demolish the station given its run-down nature, the potential liability issues, and the revenue potential of the land.

If CN did want to demolish the station , it can’t at the moment because it is protected by both municipal and provincial heritage status. So far the question of heritage status has not yet come up in the discussions.

District of Kitimat Council first passed a bylaw giving the station heritage status in September 1985.The municipal heritage status of the station is part of the official Kitimat Community Plan, adopted by council in 2008.

The railway stations in Prince Rupert and Smithers are designated under the federal Heritage Railway Stations Act.

Only designated heritage railway stations that are still owned by a railway company under federal jurisdiction are subject to the nationwide Heritage Railway Stations Protection Act. Under the act no railway company may in any way alter, demolish, or transfer ownership of a designated heritage railway station without the authorization of the federal cabinet.

In the case of Kitimat, the Heritage Group has not yet officially asked CN to support designation.

CN officials, speaking to the heritage volunteers, have told them that the station is an “eyesore” and there is “revenue potential” from the station site as Kitimat gears up for the building of the LNG Canada plant and other projects including a proposed propane terminal.

Railway stations as brands

To understand what makes the Kitimat station unique, you have to know about the history of railway station construction in North America.

From the mid-nineteenth century until the First World War, a time when railways were the prime form of transportation, railway stations were designed to both attract paying passengers and to promote the railway brand. The railways hired the leading architects of the day to design metropolitan stations in grand style, often neo Classical like Toronto’s Union Station or Grand Central in New York or “Romanesque” such as Union Station in Nashville, Tennessee (now a Marriot Hotel) that resembles the style of Canada’s Parliament Buildings.

Montreal’s Windsor Station, once the headquarters for Canadian Pacific was also built in a Romanesque style.

See Time Magazine’s selection of the world’s ten most beautiful railway stations and Fodor’s travel has a list of what it believes to be the world’s 20 most beautiful main line stations .

The same care in architectural design and construction was applied to even the smallest railway stations in those early years—although many were based on same designs from stop to stop.

When the Grand Trunk Pacific was building the line to Prince Rupert a century ago the GT built iconic smaller stations (designated by the Plan Number 100-152) along the route, with fourteen in the Smithers subdivision, including at Tyee, Kitwanga and Kwinitsa. (See Vanishing BC Grand Trunk Pacific Stations)

The latter station is now part of the Kwinitsa Station Railway Museum & Park in Prince Rupert.

The Prince Rupert station built in 1921 is an example of a utilitarian brick box that has federal protection.

The designation says the Prince Rupert Station is an example is “significant as a very early example of a public building in the Modern Classical style. Executed in brick and trimmed with Tyndall limestone, the station design combines traditional composition with simple, stripped-down classical detailing.”

The Smithers Station is considered more special it is an important and rare example of the custom-designed “special stations” built by the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway (GTP) at several divisional points along its transcontinental line. This small group of specially designed stations represented a departure from the GTP’s overall policy of rigid standardization in depot design. (like the ones at Tyee, Kwinitsa and Kitwanga)

End of an Era

That era of great railway stations ended in 1929 with the Great Depression when commerce largely collapsed. Railways in North America had little money to spend on grand passenger stations. Then came the Second World War when the priority for the railways was supporting the war effort.

Railway historians say that after 1945 most spending for North American railways was to replace aging steam locomotives with new diesel locomotives. The railways also had to retire old rolling stock such as boxcars that had been kept in service during the war.

That meant even in the post war decade from 1945 to 1955 constructing new stations was not a priority. Those stations that were built, mostly in the United States, replaced buildings that were no longer usable. Most were “modern” brick boxes based on a utilitarian design that reached back to the 1920s or the newer “brutalist” buildings of mostly poured concrete.

Kitimat was a different case—there was a brand new branch line from Terrace. That meant Kitimat needed a railway station.

The architects who assessed the Kitimat station say it is an example of the modernist “form follows function” style of architecture popularized by Frank Lloyd Wright. The load bearing 2 x 6 trusses align the exterior walls which was one of Wright’s innovative ideas.

The station was designed by CN staff. The 1992 architect, John Goritos, said, “it was designed to suit the site and wasn’t a replica of any of other CN railway stations.”

The architects say that one reason the Kitimat Station was built of wood was not only that it had to be constructed quickly but the light weight was suited to the site which was on the Kitimat River flood plain filled in with sandy landfill.

Building the Kitimat branch line

As Alcan was planning and building Kitimat, the company signed transportation contracts with CN. That was the reason the branch line was built to the townsite, then past the sandhill to the aluminum smelter.

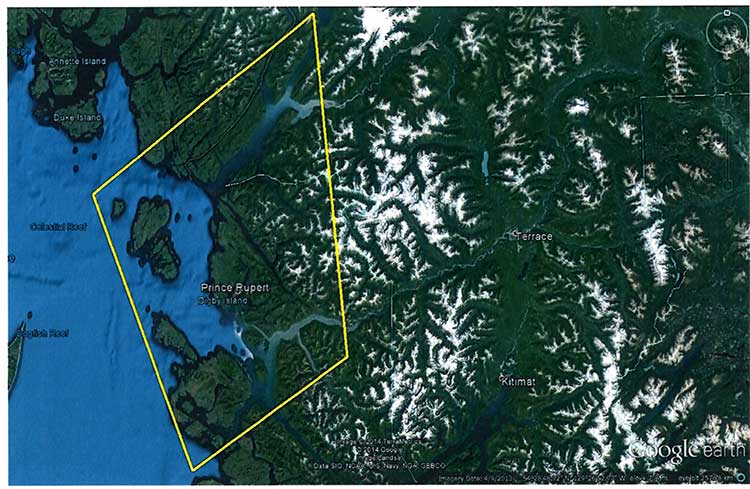

CN worked to build the new branch line for 38.5 miles crossing “difficult terrain of the area, including swamps, hard clay, rocks and watersheds.’ The route included three steel Pratt triangular truss bridges over the Lakelse, Wedeene, Little Wedeene Rivers and plus a number of smaller old fashioned traditional wooden trestles over creeks.

Canadian Transportation magazine reported in July 1952 that the branch line alone would cost $10 million 1952 dollars or $217,391.30 per mile.

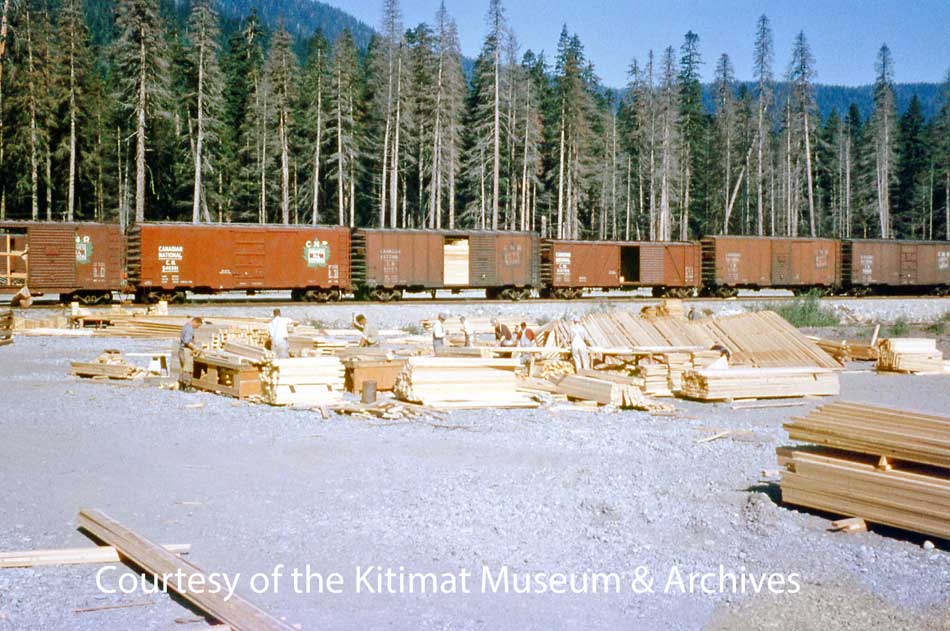

Freight travel began as soon as the branch line was completed in December 1954. Temporary huts acted as the train station when passenger service began in January 1955 but were soon overwhelmed.

Former Kitimat mayor Joanne Monaghan who worked at the station recalls that once the Alcan plant became operational although most of the ingots were shipped out by sea, there were long trains outbound with car after car loaded with aluminum ingots.

The British magazine The Sphere (an equivalent of Life or Look) covered the story this way in a report on Feb. 19, 1955.

“In the far north-west of Canada new trains have just started to run along a new railway. The line starts in a small town called Terrace and its only forty-three miles long. But its importance is out of all proportion to its length for the new terminus is in Kitimat, the new wonder aluminum manufacturing of the Canadian Aluminum Company (sic).”

The anonymous reporter photographed what The Sphere said was the arrival of the first passenger train in Kitimat. The locomotive was Canadian National steam locomotive 2129, a 2-8-0 “Consolidation” that had been in service since 1911 with three railways, the Canadian Northern and the Duluth, Winnipeg and Pacific ( a CN subsidiary in the United States) before being transferred to CN. The loco hauled three passenger coaches and two boxcars on that initial run from Terrace. Note 2.

The 2-8-0 was a heavy-duty locomotive designed for hauling freight. All those outbound boxcars filled with ingots and, inbound, as the town was being built, boxcar after boxcar filled with lumber to build the houses and stores of the brand-new town.

The “milk-run” train also serviced Lakelse Lake (where there was a whistle stop in a clearing by the tracks, which I remember from a vacation at Lakesle in the summer of 1957) as well as “stations” (again really just clearings) on the timetable at Wedeene, Dubois, Lakelse and Thunderbird, to pick up loggers, surveyors, fishers and hunters. The trip from Lakelse to Kitimat would have taken one hour and thirty minutes if the train was running on schedule.

Once dedicated passenger service began, CN assigned another steam locomotive, a lighter 4-6-2 Pacific, Number 5000, built in 1913.

As CN was transitioning to diesel, it assigned its last remaining steam locomotives to more remote parts of Canada, like northwest BC. The Pacific, Number 5000, was retired in May 1958. The 2-8-0 Consolidation Number 2129 was scrapped in May 1960.

RELATED: The Kitimat branch line operating trestle bridges

The station

CN put the station construction out to tender in June 55. The building was completed by the Skeena Construction Company, based in Terrace, before the end of the year.

Train was the main mode of travel between Terrace and Kitimat from December 1954 until November 1957 when the highway to Terrace was opened.

Freight operations continued to use the depot for years after passenger traffic ended.

Like many branch line railway stations in North America, the Kitimat station combined passenger and some freight and express operations (most of the freight operations were carried on down the line to Kitimat Concrete Products at the sandhill and on to the Alcan smelter.)

There was soon a lot of traffic in those days people coming in from all over the world to find work. News reports at the time said the three-hour train journey from Kitimat to Terrace was so popular that there was often “standing room only” in the passenger cars.

The trains expanded from a single passenger car to three and later several as demand grew.

The station had a large interior large waiting area with washrooms, a “restroom” and later a small coffee and snack bar was added to the waiting room.

Along a corridor were the depot office and the combined telegraph office and what was called the “repeater room.” Off the corridor were also the station keeper room and conductors’ office. There was a typical bay window operator’s room in the waiting area that looked out onto the tracks.

On the freight side were the express office and the “on hand” (goods for pick up). The original plans had had one door in on the east wall and one door out by the tracks on the west side. Two doors on the north wall added later to meet demand.

CBC Radio

On the blue prints for the station there is what is today a cryptic reference to the Telegraph-Repeater room which is the part of the building where we see the Canadian National Logo today. The role of the telegraph – more likely teletype by the 1950s—is obvious. The telegraph office operated for many years after passenger service ended.

It turns out the “repeater” was the first transmitter for CBC Radio in Kitimat. Canadian National Telegraphs operated most non-telephone communications in Canada along its railway lines.

CN had actually had some of the first radio stations in Canada, which were later taken over by the CBC when the Parliament created the public broadcaster.

So, in the Kitimat Station there was a LPRT or a Low Power Relay Transmitter. The “radio” signal came into Kitimat via a CN landline for broadcast. The LPRT was designed to be sited in a location were there was no other coverage or before an actual transmitter was built.

The railway company domination of telecommunications continued in 1967 when CN and CP telegraph services merged to form CNCP telecommunications. That company was later sold to Rogers when the railways got out of the telecommunications business they had founded in the previous century.

Some smaller locations across Canada still have CBC LPRTs where it is not economic to build a transmitter. Today the signal is downlinked from satellite.

CN and the station were also the conduit for secure government communications, including the RCMP. It also transmitted the Canadian Press wire service. Later BC Tel (now Telus) took over many of those functions.

End of passenger service

CN stopped passenger rail service to Kitimat in November 1957 almost as soon as then Highway 25 to Terrace was completed, although the station was still used to coordinate freight and express operations for a few years after that.

In the 1960s, passenger traffic on railways across North America plummeted as the era of the car and air travel became more the normal way to go.

CN used the station for storage in the 1970s and let it deteriorate and at one point it was vandalized. It was briefly owned by the District of Kitimat, but ownership has since reverted to CN.

Today’s train stations were most often just glass and steel, if there were stations at all. Many new stations are glass covered platforms with perhaps a small ticket office (and if passengers are lucky, washrooms).

The Kitimat CN Station is a unique snap shot of Canadian railway architecture and construction from the mid 50s that wasn’t duplicated.

CN has boarded up the building and says it is an “eyesore” and has told the heritage group that it is not structurally sound and should be moved from the site or be demolished.

Architectural assessments

The two architects reported that the station is a one story 3500 square foot structure supported by 2 x 6 fir trusses and 2 x 4 stud walls set in concrete slab. The roof trusses appear to be made of red cedar. As far as both architects could tell (access was somewhat limited) both the fir and reds cedar have survived the previous 62 years largely intact.

The roof was made of aluminum shingles, which were popular at the time as part of what was called “machine age allure” of the “space age” Streamline Moderne and “Googie” forms of architecture. The aluminum shingles, as well as the flashing were well suited for Kitimat because aluminum aged well, and snow would slide off an aluminum roof easier than traditional asphalt shingles.

The problem with the roof is that the sheathing between the red cedar and the aluminum has warped over the decades and that has displaced or heaved most of the aluminum shingles. The fascia will also have to be replaced.

The station hasn’t been heated or properly maintained for many years. That means apart from the structural walls, the rest mostly plywood and plasterboard has deteriorated markedly.

Asbestos

The greatest mistake—in retrospect—and the greatest challenge is the widespread use of asbestos in the building.

It appears that the CN architects and structural engineers in 1955 who designed the station wanted to add to that “machine age allure” by using the “modern” asbestos cladding. Before that almost all the smaller Grand Trunk and CN stations in western Canada had stucco on the exterior walls. In retrospect if CN had stuck with stucco, the station would—allowing for the poor maintenance– probably be in better shape. There are houses in Kitimat with stucco walls that have survived the elements for 50 to 60 years. If the walls were stucco, there would not be today’s cost of removing asbestos.

The most obvious use of asbestos is in the cladding or siding on the walls of the station which was a popular material up until the 1980s when the cancer risk from asbestos was realized. In the parts of the station which had linoleum floor—the passenger and office areas—it is likely that linoleum from that era contained asbestos. There is bare concrete floor for baggage express storage and heater rooms, so those are areas where there is presumably no asbestos in the flooring.

Asbestos was also wrapped around many of the building’s mechanical infrastructure and heating ducts. The soffit under the eaves may also contain asbestos.

There is so much asbestos that even if CN wanted to demolish the station the company couldn’t just bring in a backhoe or bulldozer and pull it apart as is done some other cases were there is no asbestos.

Under BC law, the asbestos would have to be safely removed by an asbestos qualified removal company before a demolition permit can be issued.

Renovating also requires a BC qualified asbestos abatement contractor.

In both cases, there has to be a hazardous material survey prior to any work commences. During the work—whether demolition or renovation—there has to be continuous hazardous material and air quality monitoring in the area. (Noting that the station is close to the Kitimat Hotel and service centre businesses)

It appears that CN hasn’t really bothered to undertake a detailed cost benefit analysis. The question is how much cost difference would there be in safely removing the asbestos prior to demolition and the cost of safely removing the asbestos prior to restoration?

Another question that has to be ironed out is who is responsible for the asbestos. CN owns the building and is currently responsible. If, as originally proposed, CN sold the building to the Kitimat Heritage for one dollar, the heritage group would then be responsible. If the heritage group gets to lease the building from CN, then CN, as the landlord, is likely still responsible for the upkeep of the building—a cost that CN apparently, at present, doesn’t want to undertake.

Worksafe BC must be notified of any project where asbestos is being removed (ws0303-pdf-en) PDF

Links

Province of British Columbia

Management of Waste Asbestos

Worksafe BC Asbestos

Stay or go? And if go, where?

Kitimat faces two choices with the station. To keep it on the current site or to move it elsewhere.

At present, according to the report by Kitimat Heritage presented to District of Kitimat Council, CN would like the building moved away from a potential revenue producing area along the right-of-way.

The Kitimat Heritage group wants the station to remain in place as the role as a train station is part of the Kitimat’s history. As the report says, “The building is not heritage without its provenance—the rail line.”

Both architect Alora Griffin and some building experts say it cannot be moved because the original design placed the load bearing trusses on the concrete pad foundation and therefore there is no floor that would support the station if it was to be moved.

That raises another question, which the far away CN executives have probably never considered because they appear to be clearly unfamiliar with Kitimat infrastructure is where would an intact station be moved to?

The bottle neck would be the Kitimat River/Haisla Boulevard bridge which was built back in 1954, a bridge that urgently requires a seismic upgrade at very least and should be replaced if it is to sustain loads of trucks heading the LNG Canada construction site.

The current District limits for crossing the bridge call for a height restriction of four metres. The maximum clearance on the bridge is 4.2 metres or 13 feet nine inches in height. The maximum weight is 65,000 kilograms or 143,000 pounds. The station is just over nine metres or 29 feet high, which means the station would never fit onto the Haisla Bridge. So why move the station from its current location?

If a contractor found a way to move across the Haisla Bridge, however unlikely, by splitting up the building, costs of moving such a building are determined by the size of the building, what work has to be done to the building prior to moving, the distance moved and incidentals such as working with BC Hydro and telecom companies if overhead wires are in the way, cutting down trees if necessary, traffic control or traffic restrictions and other problems a moving company might run into.

So far, no company has been involved that specializes in moving large structures, including heritage structures.

The average minimum cost of moving a residential house in the United States can be $16 a square foot or more, so the minimum cost of moving the 3,500 square foot station—if the sound parts of the structure can actually be moved—would probably begin at least $60,000. Actual costs are usually much higher.

The bridge restrictions mean that the station would have to remain in the service centre anyway.

So why move it?

Another possibility that was raised by local contractors is dismantling the structure, numbering the salvageable parts such as trusses, beams and roof supports and reconstructing the building elsewhere. . One factor is how the trusses would be removed from the concrete base and rebuilt elsewhere in Kitimat.

That latter solution, however, is considered by many to be cost prohibitive. That evaluation would have to be made a qualified restoration architect. A check of available records shows that many–not all– of the CN stations that have been moved are in the prairie provinces where logistics are much easier.

Restoring the station

Kitimat Heritage is asking that the funds CN would have to spend in any case to demolish the building instead be put toward restoration.

The aim of the heritage group is to convert it into a community meeting space, perhaps with a restaurant and a small museum or other guide to Kitimat Heritage.

The heritage group wants a land lease from CN, but the company says a lease at present is impossible due to liability issues. CN has told the heritage group that if was to lease the building it would want $5,000 per year in rent, a $50,000 letter of credit and $10 million in liability insurance.

CN, as the present owner of the station, is, of course, currently solely responsible for any current liability issues that may occur.

CN has told the heritage group that it doesn’t entertain land sales within 100 feet of its right-of-way which is why the railway wants the station moved if it is sold (but as noted above there is no where for the station to go). That is why the heritage group wants a lease.

There are dozens of heritage railway stations across Canada that are still owned by CN and thus have federal protection. (see Note Three below for the list of CN Stations).

It is unlikely that preserving the Kitimat Station would have any adverse effect on CN’s bottom line. In 2018, CN had revenues of $14.321 billion and an operating income of $5.493 billion. The annual report says the railway carried $250 billion worth of goods in 2018 over 20,000 route miles in Canada and the United States. CN buildings were worth $1.186 billion in 2018, according to the report. The Kitimat Station is still on the CN books (and accounting for depreciation as reported in the annual report) and is a miniscule asset.

If an agreement is reached with CN, then the heritage group would have to embark on a fund-raising effort. The next step would be to hire an architect, either a local architect or one who specializes in heritage restoration.

The building would also have to be brought up to current seismic standards and meet the current British Columbia building code for public buildings.

To bring it up to code an architect would have to redesign building and coordinate with electrical, mechanical and structural engineers. Structural engineer would have to asses the condition of the trusses and other parts of the building for possible defects and possible needed upgrades.

To restore the building the customary procedure is to ask three local contractors for a realistic estimate of the cost (not a low bid bid). To be sure, the heritage group should also ask for a bid for a contractor who specializes in restoration. A restoration specialist would likely identify hidden costs or unexpected savings.

What’s next?

The heritage group wants to come to an agreement with CN before proceeding to ask the community for financial and volunteer support.

Although the discussion between the heritage group and CN have been fruitful so far, it appears from CN’s insistence that the station be moved that the company has not bothered to fully research either the heritage of the Kitimat Station nor the geography and geology of Kitimat.

If CN had done a thorough appraisal of the situation, they would know that it is unlikely that the station could cross the Haisla Bridge and thus should stay in situ.

The proposed Pacific Traverse Energy propane project would greatly add to the rail traffic in the area –and also add to CN’s revenue. There are two proposed sites for a rail staging yard, one about three kilometres north of the service centre on Crown Land and the second on Rio Tinto owned track close to the station location—which is probably what CN means when it says the site has “revenue potential.” The current estimate is that the project would require 60 tank cars each day to service an export terminal near Bish Cove.

So far, only pure rumour and speculation have said that the propane project is an impediment to saving the station.

At some point the company should be invited to join the discussion. Since Pacific Traverse Energy has said in its presentation to council that the company is going to embark on a “rigorous program of community engagement” this year and that it is committed to “economic, social, cultural and economical sustainability.” Emphasizing the word cultural means that the company could prove its commitment to the community of Kitimat by taking into consideration the future of the CN Station in any planning and decisions on land use or by helping to pay for station restoration of out a budget of $400 million while ensuring the safety of the station area if the project proceeds.

The cost of restoring the station is likely to be substantial and not only government but corporate funding as well as in kind contributions from local contractors and businesses will be needed to fully restore the station and make it operational as a community centre.

One factor is that the railway line from Terrace and the train station were built by CN on behalf of the then Aluminum Company of Canada, a company that promised CN back in the 50s at least a million dollars a year in revenue. (According to the Bank of Canada inflation calculator one million dollars in 1950 would be 11 million dollars in 2019—which may nor may not reflect how much Rio Tinto actually pays CN). It’s clear that both CN and Rio Tinto have profited from the rail line for the past almost 70 years and it’s time that some of those profits were applied to preserving Kitimat’s heritage.

Kitimat factory town or more?

Most railway heritage buildings and heritage railways around the world are maintained and operated by volunteers usually railway buffs, heritage activists and retired railway employees. There are few, if any, railway employees retired in Kitimat (although there may be some in Terrace or Prince Rupert). This could prove a problem in Kitimat where the same small group of volunteers are engaged in multiple efforts while others in the community seldom contribute. On the other hand, the restoration of the station and its operation as a community meeting place could bring out new volunteers.

The bigger picture that Kitimat has to decide on is what kind of town will this be in the future?

Back in the nineteenth century, when those iconic railway stations were built across North America, many mining, smelting and logging towns built equally impressive “opera houses” or other culture landmarks that are still preserved today.

While Kitimat never had a grand opera house, there is the station that marks the town’s early settler history.

The LNG Canada final investment decision approval and the growth of Asian markets for hydrocarbon energy (at least for the next few decades) and quality aluminum, means that the industrial base of Kitimat is assured.

Tourism has always been a low priority and culture has been an almost a zero priority.

So, is Kitimat going to be just an industrial town or is it Kitimat going to be more than that with cultural amenities for its residents and to be more than a tourist draw for mostly aging recreational fishers?

Whatever decision is made on the CN station will help decide the road to that future.

LINK

Kitimat Museum & Archives contact page.

Note 1.

A small boy is seen in the photograph of the station wearing a “coonskin cap.” The Disney TV series Davy Crockett was broadcast from December 1954 to February 1955. Two follow up movies starring Fess Parker were Davy Crockett, King of the Wild Frontier, 1955, and Davy Crockett and the River Pirates, 1956. Disney heavily marketed the coonskin cap to small boys, selling at one point 5,000 a day in the United States. Most were made of faux fur. Although Kitimat did not have television until years later, the cap likely dates the photo to the summer or fall of 1955, the height of the coonskin cap craze. Wikipedia.

A small boy is seen in the photograph of the station wearing a “coonskin cap.” The Disney TV series Davy Crockett was broadcast from December 1954 to February 1955. Two follow up movies starring Fess Parker were Davy Crockett, King of the Wild Frontier, 1955, and Davy Crockett and the River Pirates, 1956. Disney heavily marketed the coonskin cap to small boys, selling at one point 5,000 a day in the United States. Most were made of faux fur. Although Kitimat did not have television until years later, the cap likely dates the photo to the summer or fall of 1955, the height of the coonskin cap craze. Wikipedia.

Note 2

You can see a Canadian Pacific 2-8-0 steam locomotive similar to the CN loco that made the first trip to Kitimat at the Kettle Valley Steam Railway in Summerland.

Note 3

A list of Canadian National (or affiliate) heritage railway stations protected by the federal government. This list does not include stations owned by VIA Rail, Canadian Pacific or smaller Canadian Railways. There should be no reason that Kitimat’s station cannot join this list. (The George Little House station in Terrace was not originally a railway station but a heritage house that was moved to the trackside as a VIA station)

British Columbia

Kamloops

Kelowna

McBride

Prince Rupert

Smithers

Vancouver

Alberta

Jasper

Saskatchewan

Biggar

Humboldt

Melville

Moose Jaw

North Battleford

Manitoba

Churchill

Dauphin

Gillam

McCreary

Neepewa

Portage la Prairie

Rivers

Roblin

The Pas

Ontario

Alexandria

Barrie

Auroa

Belleville

Brampton

Brantford

Casselman

Chatham

Cobourg

Comber

Ernestown

Fort Frances

Galt/Cambridge

Georgetown

Guelph

Hamilton

Hornepayne

Kingston

Kitchener

Leamington

Maple

Markham

Nakina

Newmarket

Niagara Falls

North Bay

Orillia

Owen Sound

Parry Sound

Port Hope

Prescott

Sioux Lookout

St. Thomas

Stratford

Toronto Union Station

Woodstock

Quebec

Amqui

Clova

Joliette

Macamic

Matapédia

Mont-Joli

Montréal

New Carlisle

Port Daniel

Saint-Hyacinthe

Saint-Pascal

Sainte-Anne-de-la-Pérade

Sayabec

Senneterre

Shawinigan

Sherbrooke

New Brunswick

Edmunston

Grand Falls

Sackville

Sussex

Nova Scotia

Amherst