A new draft report for the U.S. Congress from the United States Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration takes new aim at Enbridge for failures in its pipeline leak detection and response system.

A new draft report for the U.S. Congress from the United States Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration takes new aim at Enbridge for failures in its pipeline leak detection and response system.

Not that the PHMSA is singling out Enbridge, the report is highly critical of leak detection systems on all petroleum and natural gas pipeline companies, saying as far as the United States is concerned, the current pipeline standards are inadequate.

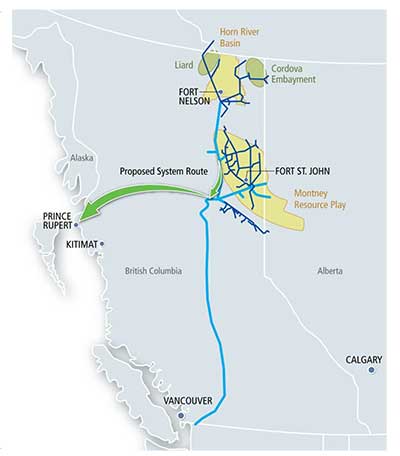

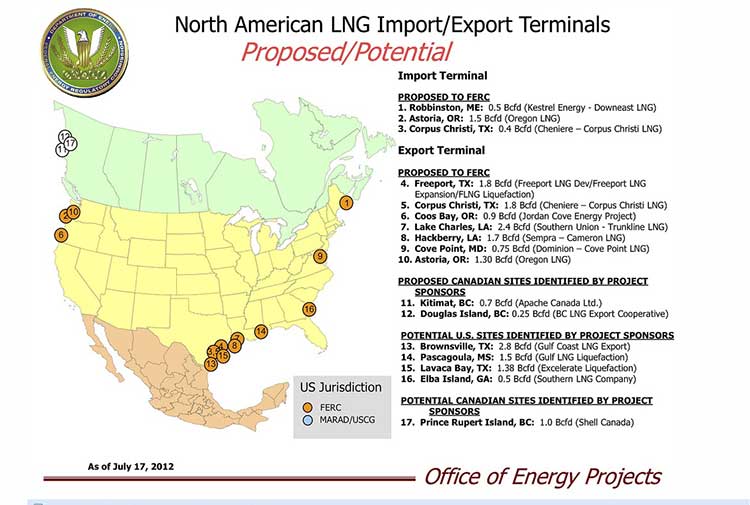

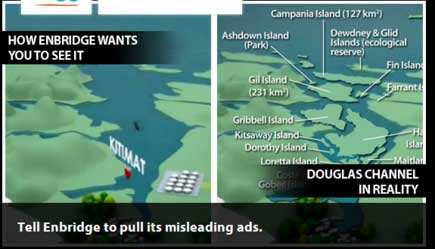

The release of the “Leak Detection Report” written by Kiefner & Associates, Inc (KAI) a consulting firm based in Worthington, Ohio, comes at a critical time, just as Enbridge was defending how it detects pipeline leaks before the Joint Review Panel questioning hearings in Prince George, where today Enbridge executives were under cross-examination by lawyers for the province of British Columbia on how the leak detection system works.

In testimony on Wednesday, October 12, Enbridge engineers told the Joint Review Panel that the company’s pipelines are world-class and have a many prevention and detection systems.

Northern Gateway president John Carruthers testifed there is no way to eliminate all the risks but the company was looking for the best way of balancing benefits against the risk.

However, the KAI report points out that so far, all pipeline company cost-benefit analysis is limited by a short term, one to five year point of view, rather than looking at the entire lifecycle of a pipeline.

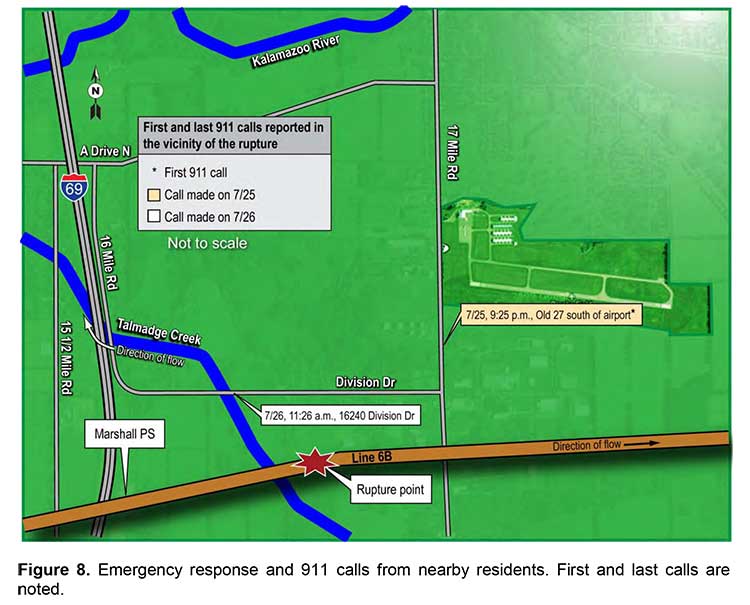

Two Enbridge spills, one the well-known case in Marshall Michigan which saw bitumen go into the Kalamazoo River and a second in North Dakota, both in 2010, are at the top of the list in the study for PHMSA by the consulting firm.

On the Marshall, Michigan spill the KAI report goes over and adds to many of the criticisms of Enbridge in the National Transportation Safety Report in July which termed the company’s response like the “Keystone Kops.”

The second spill, in Neche, North Dakota, which, unlike the Marshall spill, has had little attention from the media, is perhaps equally damning, because while Enbridge’s detection systems worked in that case–the KAI report calls it a “text book shutdown”– there was still a spill of 158,928 gallons (601,607 litres) of crude oil, the sixth largest hazardous liquid release reported in the United States [between 2010 and 2012] because Enbridge “did not plan adequately for containment.”

(The KAI report also examines problems with natural gas pipelines, including one by TransCanada Northern Border line at Campbell, Wyoming in February 2011. Northwest Coast Energy News will report on the natural gas aspects of the report in a future posting.)

The highly technical, 270-page draft report was released on September 28, as Enbridge was still under heavy criticism from the US National Transportation Safety Board report on the Marshall, Michigan spill and was facing penalties from the PHMSA for both the Marshall spill and a second in Ohio.

Looking at overall pipeline problem detection, KAI says the two standard industry pipeline Leak Detection Systems or LDS didn’t work very well. Between 2010 and 2012, the report found that Computational Pipeline Monitoring or CPMs caught just 20 per cent of leaks. Another system, Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition or SCADAs caught 28 per cent.

Even within those acronym systems, the KAI report says major problem is a lack of industry standards. Different companies use different detector and computer systems, control room procedures and pipeline management.

The report also concludes that the pipeline industry as a whole depends far too much on internal detectors, both for economic reasons and because that’s what the industry has always done. External detectors, the report says, have a better track record in alerting companies to spills.

A significant number of spills are also first reported by the public or first responders, rather than through the pipeline company system and as KAI says of Enbridge, “Operators should not rely on the public to tell them a pipeline has ruptured.”

The consultants also say there are far too many false alarms in spill detection systems.

Although the KAI report concentrates on the United States, its report on Enbridge does raise serious questions about how the company could detect a pipeline breach or spill in the rugged northern British Columbia wilderness where the Northern Gateway Pipeline would be built, if approved by the federal government.

The report comes after the United States Congress passed The Pipeline Safety, Regulatory Certainty, and Job Creation Act, which was signed into law by President Barack Obama on January 3, 2012. The law called on a new leak detection study to be submitted to Congress that examines the technical limitations of current leak detection systems, including the ability of the systems to detect ruptures and small leaks that are ongoing or intermittent. The act also calls on the US Department of Transportation to find out what can be done to foster development of better technologies and economically feasible ways of detecting pipeline leaks. The final report must be submitted to Congress by January 3, 2013.

(The draft report does note in some ways, Canadian standards for detecting pipeline leaks are better than those in the United States. For example, Canada requires some pipeline testing every year, the United States every five years. It also finds European pipeline monitoring regulations also surpass those in the United States).

The spills studied in the report all found weaknesses in one or more of those three areas: people, company procedures and the technology. It appears that the industry agrees, at least in principle, with executives telling the consultants:

The main identified technology gaps – including those identified by operators – include: reduction or management of false alarms; applicable technical standards and certifications; and value / performance indicators that can be applied across technologies and pipelines.

The report echoes many of the findings of the US National Transportation Safety Board in its examination of the Enbridge Marshall, Michigan spill but it applies to all pipeline companies, noting:

Integration using procedures is optimal when it is recognized that alarms from the technology are rarely black-and-white or on/off situations. Rather, at a minimum, there is a sequence: leak occurrence; followed by first detection; followed by validation or confirmation of a leak; followed by the initiation of a shutdown sequence. The length of time that this sequence should take depends on the reliability of the first detection and the severity of the consequences of the release. Procedures are critical to define this sequence carefully – with regard to the technology used, the personnel involved and the consequences – and carefully trained Personnel are needed who understand the overall system, including technologies and procedures.

We note that there is perhaps an over-emphasis of technology in LDS. A recurring theme is that of false alarms. The implication is that an LDS is expected to perform as an elementary industrial automation alarm, with an on/off state and six-sigma reliability. Any alarm that does not correspond to an actual leak is, with this thinking, an indicator of a failure of the LDS system.

Instead, multiple technical studies confirm that far more thought is required in dealing with leak alarms. Most technologies infer the potential presence of a leak via a secondary physical effect, for example an abnormal pressure or a material imbalance. These can often be due to multiple other causes apart from a leak.

The report takes a critical look at the culture of all pipeline companies which divides problems into leaks, ruptures and small seeps. Under both pipeline practice and the the way problems are reported to the PHMSA in the US a “rupture is a situation where the pipeline becomes inoperable.” While a rupture means that a greater volume of petroleum liquid or natural gas is released, and is a higher priority than a leak or seep, the use of language may mean that there is a lower priority given to those leaks and seeps than the crisis created by a rupture.

(Environmental groups in British Columbia have voiced concerns about the cumulative affect of small seeps from the Enbridge Northern Gateway that would be undetectable under heavy snow pack either by an internal system or by external observation)

Overall, the report finds serious flaws to the way pipeline companies are conducting leak detection systems at the moment, including:

- Precisely the same technology, applied to two different pipelines, can have very different results.

- Leak Detection Systems do not have performance measures that can be used universally across all pipelines. Compounding the problem are different computer systems where software, program configuration and parameter selection all contribute, in unpredictable ways, to overall performance.

- Many performance measures present conflicting objectives. For example, leak detection systems that are highly sensitive to small amounts of lost hydrocarbons are also prone to generating more false alarms.

- The performance of a leak detection system depends critically on the quality of the engineering design, care with installation, continuing maintenance and periodic testing.

- Even though an internal technology may rely upon simple, basic principles, it is in fact, complex system that requires robust metering, robust SCADA and telecommunications, and a robust computer to perform the calculations. Each of these subsystems is individually complex.

- Near the inlet and the outlet of the pipeline a leak leads to little or no change in pressure. Flow rates and pressures near any form of pumping or compression will generally be insensitive to a downstream leak

- Differences in any one of these factors can have a dramatic impact on the ultimate value of a leak detection system.

The report goes on to say:

There is no technical reason why several different leak detection methods can not be implemented at the same time. In fact, a basic engineering robustness principle calls for at least two methods that rely on entirely separate physical principles.

The report strongly recommends that pipeline companies take a closer look at external leak detection systems. Even though the US Environmental Protection Agency began recommending the use of external detection as far back as 1988, the companies have resisted due to the cost of retrofitting the legacy pipeline network. (Of course if the pipeline companies had started retrofitting with external detectors in 1988 they would be now 24 years into the process).

KAI says:

- External leak detection is both very simple – relying upon routinely installed external sensors that rely upon at most seven physical principles – and also confusing, since there is a wide range of packaging, installation options, and operational choices to be considered.

- External leak detection sensors depend critically on the engineering design of their deployment and their installation.

- External sensors have the potential to deliver sensitivity and time to detection far ahead of any internal system.

- Most technologies can be retrofitted to existing pipelines. In general, the resistance to adopting external technologies is, nevertheless, that fieldwork on a legacy pipeline is relatively expensive.

- The report goes on to identify major bureaucratic roadblocks within pipeline companies. Like many other big corporations, walls exist that prevent the system from working well

- A particular organizational difficulty with leak detection is identifying who “owns” the leak detection system on a pipeline. A technical manager or engineer in charge is typically appointed, but is rarely empowered with global budgetary, manpower or strategic responsibilities. Actual ownership of this business area falls variously to metering, instrumentation and control, or IT.

The report calls for better internal standards at pipeline companies since with leak detection “one size does not necessarily fit all”.

It also notes that “flow metering is usually a central part of most internal leak detection systems,” but adds “flow meter calibration is by far the most laborious part of an internal system’s maintenance.

Also, the central computer and software technology usually has maintenance requirements far greater than most industrial automation and need special attention.”

While a company may do a cost benefit analysis of its leak detection system and risk reduction system it will generally emphasize the costs of the performance and engineering design of the leak detection system, the companies usually place less emphasis on the benefits of a robust system, especially the long term benefits.

At present the pipeline companies look at the benefit of leak detection as a reduction in risk exposure, or asset liability, “a hard, economic definition… understood by investors.” But the report adds that leak detection systems have a very long lifetime and over that life cycle, the cost-benefit approaches the reduction in asset liability caused by the system, when divided by annual operational costs. However, since pipeline companies budget on a one to five year system the long term benefit of robust, and possibly expensive spill detection is not immediately apparent.

Enbridge

The consultants studied 11 US oil spills, the top two with the greatest volume were from Enbridge pipelines. The others were from TE Products Pipeline, Dixie Pipeline, Sunoco, ExxonMobil, Shell, Amoco, Enterprise Products, Chevron and Magellan Pipeline. Not all US spills were used in the KAI report, the 11 were chosen for availability of data and documentation.

The largest spill in the KAI study was the pipeline rupture in Michigan at 843,444 gallon (3,158,714 litres) which has been the subject of continuing media, investigative and regulatory scrutiny. The second spill in North Dakota, has up to now received very little attention from the media. That will likely change once the US Congress gets the final report. Even though the Neche, North Dakota spill, has been described as “text book case” of a pipeline shutdown, there was still a large volume of oil released.

Marshall, Michigan spill

On the Marshall, Michigan spill that sent bitumen into the Kalamazoo River the report first goes over the facts of the 843,444 gallon spill and the subsequent release of a highly critical report from the US National Transportation Safety Board. It then looks at the failures of Enbridge’s detection system from the point of view mandated for the report to Congress:

The pipeline was shutting down when the ruptured occurred. Documentation indicates that a SCADA alarm did sound coincident with the most likely time of the rupture. It was dismissed. The line was shut down for around 10 hrs and crude oil would have drained from the line during this time.

On pipeline start up, alarms in the control room for the ruptured pipeline sounded. They were dismissed. This was repeated two more times. The pipeline was shut down when the control room was notified of the discharge of the crude oil by a member of the public. The time to shut down the pipeline is not relevant here because of the 17 hours that elapsed after the rupture occurred.

The review identified issues at Enbridge relevant to this Leak Detection Study:

1. Instrumentation on a pipeline that informs a controller what is happening to the pipeline must be definitive in all situations.

2. However, the instrumentation did provide warnings which went unheeded by controllers.

3. Instrumentation could be used to prevent a pump start up.

4. Operators should not rely on the public to tell them when a pipeline has ruptured.

5. Pipeline controllers need to be fully conversant with instrumentation response to different operations performed on the pipeline.

6. If alarms can be cancelled there is something wrong with the instrumentation feedback loop to the controller. This is akin to the low fuel warning on a car being turned off and ignored. The pipeline controller is part of an LDS and failure by a controller means the LDS has failed even if the instrumentation is providing correct alarms.

7. If the first SCADA alarm had been investigated, up to 10 hours of pipeline drainage to the environment might have been avoided. If the second alarm had been investigated, up to 7 hours of pumping oil at almost full capacity into the environment might have been avoided.

8. CPM systems are often either ignored or run at much higher tolerances during pipeline start ups and shutdowns, so it is probable that the CPM was inoperative or unreliable. SCADA alarms, on the other hand, should apply under most operating conditions.

Neche, North Dakota spill

At approximately 11:37 pm. local time, on January 8, 2010, a rupture occurred on Enbridge’s Line 2, resulting in the release of approximately 3000 barrels or 158,928 gallons of crude oil approximately 1.5 miles northeast of the town of Neche, North Dakota, creating the sixth largest spill in the US during the study period.

As the report notes, in this case, Enbridge’s detection system worked:

At 11:38 pm., a low-suction alarm initiated an emergency station cascade shutdown. At 11:40 pm., the Gretna station valve began closing. At 11:44 pm., the Gretna station was isolated. At 11:49 pm., Line 2 was fully isolated from the Gretna to Donaldson pump stations.

Documentation indicates a rapid shut down on a low suction alarm by the pipeline controller. From rupture to shut down is recorded as taking 4 minutes. The length of pipeline isolated by upstream and downstream remotely controlled valves was 220,862 feet. The inventory for this length of line of 26-inch diameter is 799,497 gallons. The release amount was around 20 per cent of the isolated inventory when the pipeline was shut down.

The orientation of the 50-inch long rupture in the pipe seam is not known. The terrain and elevation of the pipeline is not known. The operator took around 2 hours and 40 minutes to arrive on site. It is surmised that the rupture orientation and local terrain along with the very quick reactions by the pipeline controller may have contributed to the loss of around 20 per cent of the isolated inventory.

The controller was alerted by the SCADA. Although a CPM system was functional the time of the incident it did not play a part in detecting the release event. It did provide confirmation.

But the KAI review identified a number of issues, including the fact in item (7) Enbridge did not plan for for containment and that containment systems were “under-designed.”

1. This release is documented as a text book shut down of a pipeline based on a SCADA alarm.

2. The LDS did not play a part in alerting the pipeline controller according to

documentation. However, leak detection using Flow/Pressure Monitoring via SCADA

worked well.

3. Although a textbook shut down in 4 minutes is recorded, a large release volume still occurred.

4. The release volume of 158,928 gallons of crude oil is the sixth largest hazardous liquid release reported between January 1, 2010 and July 7, 2012.

5. The length of pipeline between upstream and downstream isolation valves is long at 41.8 miles.

6. If not already performed, the operator should review potential release volumes based on ruptures taking place at different locations on the isolated section.

7. The success of a leak detection system includes planning for the entire process: detection through shutdown through containment. In this case, the operator did not plan adequately for containment so that although the SCADA leak detection technology, the controller and the procedures worked well, the containment systems (isolation valves) were under-designed and placed to allow a very large spill.”

KAI Draft report on Leak Detection Systems at the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration website

Apache has a new partner in the Kitimat LNG project, Chevron Canada Ltd and, in effect, Chevron is taking over the project from Apache who has been unable to find customers for the liquified natural gas project in Asia.

Apache has a new partner in the Kitimat LNG project, Chevron Canada Ltd and, in effect, Chevron is taking over the project from Apache who has been unable to find customers for the liquified natural gas project in Asia.