The herring, now dwindling on on the Pacific Coast, was once “superabundant” from Washington State through British Columbia to Alaska and that is a warning for the future, a new study says.

A team of scientists lead by Simon Fraser University argue that the archaeological record on the Pacific Coast offers a “deep time perspective” going back ten thousand years that can be a guide for future management of the herring and other fish species.

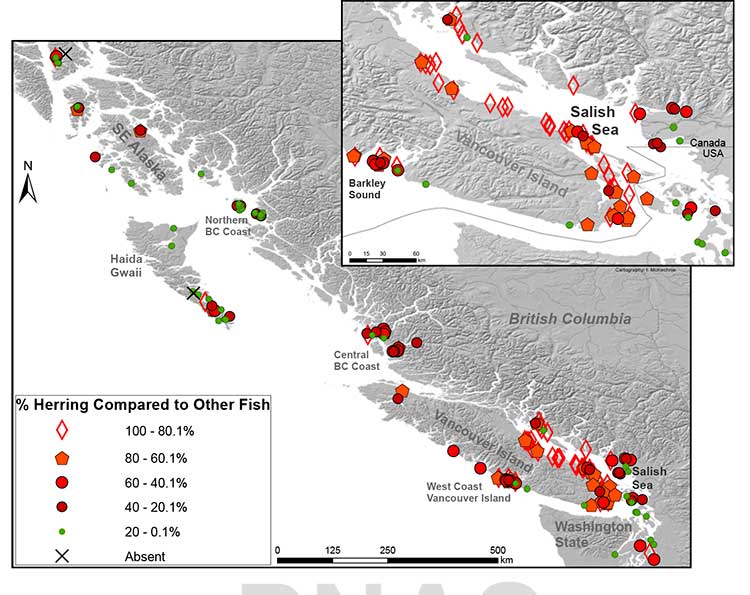

An archaeological study looked at 171 First Nations’ sites from Washington to Alaska and recovered and analyzed 435,777 fish bones from various species.

Herring bones were the most abundant and dating shows that herring abundance can be traced from about 10,700 years ago to about the mid-nineteenth century with the arrival of Europeans and the adoption of industrial harvesting methods by both settlers and some First Nations.

That means herring were perhaps the greatest food source for First Nations for ten thousand years surpassing the “iconic salmon.” Herring bones were the most frequent at 56 per cent of the sites surveyed and made up for 49 per cent of the bones at sites overall.

The study was published online Monday, February 17, 2014, in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). Simon Fraser University researchers Iain McKechnie, Dana Lepofsky and Ken Lertzman, and scientists in Ontario, Alberta and the United States are its co-authors.

The study is one of many initiatives of the SFU-based Herring School, a group of researchers that investigates the cultural and ecological importance of herring.

“By compiling the largest data set of archaeological fish bones in the Pacific Northwest Coast, we demonstrate the value of using such data to establish an ecological baseline for modern fisheries,” says Iain McKechnie. The SFU archaeology postdoctoral fellow is the study’s lead author and a recent University of British Columbia graduate.

Co-author and SFU archaeology professor Dana Lepofsky states: “Our archaeological findings fit well with what First Nations have been telling us. Herring have always played a central role in the social and economic lives of coastal communities. Archaeology, combined with oral traditions, is a powerful tool for understanding coastal ecology prior to industrial development.”

The researchers drew from their ancient data-catch concrete evidence that long-ago herring populations were consistently abundant and widespread for thousands of years. This contrasts dramatically with today’s dwindling and erratic herring numbers.

“This kind of ecological baseline extends into the past well beyond the era of industrial fisheries. It is critical for understanding the ecological and cultural basis of coastal fisheries and designing sustainable management systems today,” says Ken Lertzman, another SFU co-author. The SFU School of Resource and Environmental Management professor directs the Hakai Network for Coastal People, Ecosystems and Management.

Heiltsuk tradition

The paper says that the abundance of herring is additionally mirrored in First Nations’ place

names and origin narratives. They give the example of the 2,400-y-old site at Nulu where herring

made up about 85 per cent of the fish found in local middens. In Heiltsuk oral tradition, it is Nulu where Raven first found herring. Another site, 25 kilometres away at the Koeye River, has only has about 10 per cent herring remains and is not associated with herring in Heiltsuk tradition.

(In an e-mail to Northwest Coast Energy News, McKechnie said “there is a paucity of archaeological data from Kitimat and Douglas Channel. There is considerable data from around Prince Rupert, the Dundas Islands and on the central coast Namu/Bella Bella/ Rivers Inlet area and in southern Haida Gwaii.”)

The study says that the archaeological record indicates that places with abundant herring were consistently harvested over time, and suggests that the areas where herring massed or spawned were more extensive and less variable in the past than today. It says that even if there were natural variations in the herring population, the First Nations harvest did not affect the species overall.

It notes:

Many coastal groups maintained family-owned locations for harvesting herring and herring roe from anchored kelp fronds, eel grass, or boughs of hemlock or cedar trees. Herring was harvested at other times of the year than the spawning period when massing in local waters but most ethnohistorical observations identify late winter and springtime spawning as a key period of harvest for both roe and fish.

The herring and herring roe were either consumed or traded among the First Nations.

Sustainable harvests encouraged by building kelp gardens,wherein some roe covered fronds were not collected, by minimizing noise and movement during spawning events, and by elaborate systems of kin-based rights and responsibilities that regulated herring use and distribution.

Industrial harvesting

Industrial harvesting and widespread consumption changed all that. Large numbers of herring were harvested to for rendering to oil or meal. By 1910, the problem was already becoming clear. In that year British Columbia prohibited the reduction of herring for oil and fertilizer. There were reports at that time that larger bays on the Lower Mainland were “being gradually deserted by the larger schools where they were formerly easily obtained.”

But harvesting continued, in 1927 the fishery on eastern Vancouver Island, Columbia, processed

31,103 tons of herring. The SFU study notes that that is roughly twice the harvest rate for 2012 and would also be about 38 per cent of the current herring biomass in the Strait of Georgia.

In Alaska, reduction of herring began in 1882 and reached a peak of 75,000 tons in 1929.

As the coastal populations dwindled, as with other fisheries, the emphasis moved to deeper water. By the 1960s, the herring populations of British Columbia and Washington had collapsed. Canada banned herring reduction entirely in 1968, Washington followed in the early 1980s.

In the 1970s, the herring population off Japan collapsed, which opened up the demand for North American roe, which targeted female herring as they were ready to spawn. That further reduced the herring population so that the roe fishery is now limited to just a few areas including parts of the Salish Sea and off Sitka and Togiak, Alaska.

The First Nations food, social and ceremonial herring fishery continues.

Government fishery managers, scientists, and local and indigenous peoples lack consensus on the cumulative consequences of ongoing commercial fisheries on herring populations. Many First Nations, Native Americans, Alaska Natives, and other local fishers, based on personal observations and traditional knowledge, hypothesize that local herring stocks, on which they consistently relied for generations, have been dramatically reduced and made more difficult to access following 20th century industrial fishing

Deep time perspective

The SFU study says that some fisheries managers are suggesting that the herring population has just shifted to other locations and other causes may be climate change and the redounding of predator populations.

But the study concludes, that:

Our data support the idea that if past populations of Pacific herring exhibited substantial variability, then this variability was expressed around a high enough mean abundance such that there was adequate herring available for indigenous fishers to sustain their harvests but avoid the extirpation of local populations.

These records thus demonstrate a fishery that was sustainable at local and regional scales over millennia, and a resilient relationship between harvesters, herring, and environmental change that has been absent in the modern era.

Archaeological data have the potential to provide a deep time perspective on the interaction between humans and the resources on which they depend.

Furthermore, the data can contribute significantly toward developing temporally meaningful ecological baselines that avoid the biases of shorter-term records.

Other universities participating in the study were the University of British Columbia, University of Oregon, Portland State University, Lakehead University, University of Toronto, Rutgers University and the University of Alberta.

RELATED:

BC First Nations Opposition to Commercial Herring Fisheries supported by DFO

Fisheries minister ignored advice from own scientists

Oil spill caused “unexpected lethal impact” on herring, study shows