Analysis

Monday’s decision by LNG Canada to postpone the all-important Final Investment Decision for the Kitimat liguified natural gas project came as a momentary shock—but no real surprise. After the Brexit vote, you could see the hold button blinking from across the Atlantic.

Andy Calitz CEO of LNG Canada and a long time, experienced, executive with the lead partner, Royal Dutch Shell blamed the current market conditions for natural gas in both a news release and an investors’ conference call. However, the turmoil in the world economy brought about by Britain’s (largely unexpected) vote to leave the European Union made the postponement inevitable.

Immediately after the vote on June 23, when the now not so United Kingdom voted by 52 per cent to 48 per cent, to leave the European Union, financial analysts predicted that given the uncertainty, companies based in the United Kingdom would immediately begin to adjust their long term planning.

The stock market has stabilized and reached new highs, at least for now, but the British pound remains weak.

Most important, according to reports in the business press around the world, many long term projects by companies not only in the UK but everywhere are being re-examined, postponed or cancelled. All due to the long term uncertainty in world markets.

Even without Brexit, the situation with long term planning for the natural gas market is complicated, as LNG Canada’s External Affairs Director Susannah Pierce explained in this interview on CKNW ‘s Jon McComb show. ( It is an informative interview. Autoplays on opening the page)

“ Postpone investment decisions”

Royal Dutch Shell is one of the world’s largest corporations. It is based in the United Kingdom although its corporate headquarters are in the Netherlands (also a member of the European Union).

From June 24 to July 11 was just enough time for the bean counters and forecasters in London, Vancouver, Calgary, Tokyo and Beijing to crunch the numbers and decide that the prudent move would be to put the LNG Canada project on hold.

Rio Tinto is also a dual national company, listed on both the London and Australian stock exchanges and with its headquarters in London. (More about Rio Tinto later.)

Although both Shell and Rio Tinto are giant transnationals with operations worldwide, the turmoil in the United Kingdom, in the corridors and cubicles of the home offices, is having a psychological and personal, as well as professional, impact, meaning more of the work in those towers of London will be focused on Brexit.

The decision doesn’t mean that the LNG Canada Final Investment Decision will be on hold forever. Of all the world’s energy companies, Shell is one of the oldest and it has a solid reputation for better long term planning than some of its competitors.

In the news release, Calitz noted

I can’t say enough about how valuable this support has been and how important it will be as we look at a range of options to move the project forward towards a positive FID by the Joint Venture participants.

The news release goes on to say

However, in the context of global industry challenges, including capital constraints, the LNG Canada Joint Venture participants have determined they need more time prior to taking a final investment decision. decision.

How much time? Well, as Theresa May became the Prime Minister of Great Britain, the New York Times noted, like other media, that investment decisions are on hold:

Ms. May does not plan to depart the union quickly because it could put Britain’s negotiators under pressure, and at a disadvantage…

And the longer Britain drifts, the greater the uncertainty for businesses that could postpone investment decisions until things are clearer, potentially pushing the nation into a recession.

As Don Pittis, business columnist for CBC.ca wrote in the immediate aftermath:

The extrication of Britain from Europe will likely be more in the character of the Greek financial collapse, a seemingly endless process where each event and each piece of news has the power to set off a new round of financial fears.

And like the Greek crisis, each piece of bad news will compound fears in markets that were nervous for other reasons.

So once (and when) Theresa May invokes Article 50 that opens a two year window for Britain to leave the European Union, starting negotiations for Brexit. Then it gets complicated, if Scotland votes to leave the United Kingdom or if Northern Ireland also demands a dual referendum in both the Republic and the North on a united Ireland (as permitted under the Good Friday Peace Agreement).

Although May says she will continue to the UK`s next fixed date election, what if May calls a snap general election, with an uncertain outcome, perhaps another minority government, with seats split among several parties, including those who advocate remaining in the EU?

The price of oil is still low compared to a few years ago. That price is expected to remain low with all that the Saudis are pumping to retain market share, the Iranians want to recover from sanctions, and according to Pittis in another column, that means everyone else is pumping as well

The main thrust for Canadian producers is to build more pipelines so they can expand capacity and push ever more of their relatively expensive oil into the world supply chain. If that’s the strategy for high-cost producers, how could anyone think the world’s lower-cost producers wouldn’t be doing the same thing?

There is the glut of natural gas currently in Asian markets and no one knows what Brexit will mean. Unless there’s a drastic change in the marketplace, energy project investment will remain on hold for years to come. (So forget any dreams of a refinery anywhere on the coast. )

Rio Tinto

Brexit is also going to be a problem for London based Rio Tinto—and for the current negotiations with the Unifor local in Kitimat. Rio Tinto’s bottom line is weak because the price of iron ore, its main source of income, has been dropping. After completing the $4.8 billion Kitimat Modernization Project, Rio Tinto is spending huge amounts of money on its Oyu Tolgoi copper and gold and other minerals mine in Mongolia, a project that many analysts believe could provide up to 60 per cent of Rio Tinto profits as commodity markets recover.

Add to that US presidential election. Donald Trump has threatened to halt imports of both steel and aluminum into the United States if he actually gets to sit in the White House.

On June 29, outgoing President Barack Obama also looked at aluminum at the recent “Three Amigos” summit in Ottawa, noting in the news conference.

Given the flood of steel and aluminum on the global markets, however, it points to the fact that free trade also has to be fair trade.

That means if Hilary Clinton becomes president, she will also be looking at the state of aluminum imports to the United States market.

World conditions are a warning for the Unifor negotiating team in Kitimat. One reason for last year’s prolonged municipal strike was that Unifor spent a good deal of time planning for negotiations with the District but failed to adjust its contract demands when the price of oil unexpectedly collapsed, which meant the District had less money and a lot less flexibility.

In its negotiations with Rio Tinto, Unifor cannot make the same mistake again. There were a handful of unexpected layoffs down at Smeltersite on June 30; there could be more layoffs in the future. Mandatory overtime is a major sticking point—but that overtime demand is coming from the bean counters in Montreal and London, calculating that the overtime costs are, in the long term, less expensive than a lot of new hires.

Media reports show that Rio Tinto is in tough negotiations with its employees around the world. With LNG on hold, disgruntled employees can’t just turn off Haisla Boulevard to the old Methanex site before reaching Rio Tinto’s property line. That means Unifor should be tough but very realistic in its talks with Rio Tinto, knowing that the powers that be that hold the strings in London are more worried about what Brexit will do to the company bottom line than any temporary shutdown of the smelter by a strike.

What does this mean for Kitimat?

So the boom and bust cycle once again moves to bust.

Ellis Ross, chief councillor of the Haisla First Nation, speaking to CBC Radio said Ross said

the Haisla nation has been working to get its people jobs in the construction of the facility and related infrastructure, as well as full-time jobs once the plant opens…This was our first chance as Haisla to be a part of the economy, to be part of the wealth distribution in our area. To witness the wealth generation in our territory for the last six years but to not be a part of it, and now to continue to not be a part of it, is really distressing to us, because we had built up our entire future around this.

Mayor Phil Germuth in the same interview said

There’s no doubt that there’s going to be a little bit of hurt for a while, but we still fully believe that Kitimat is by far the absolute best location anywhere on the West Coast [for] a major LNG export facility… We are absolutely confident that it will come.

There’s time in this bust for everyone in town to recover from the hangover of the past few years of the fight over Northern Gateway and the heady hopes of the LNG rush. Demand for natural gas is not going to go away, especially as climate change raises the pressure to eliminate coal, so it is likely that LNG Canada will be revived.

It’s time to seriously consider how to diversify the Valley’s economy, making it less dependent on the commodity cycle. It’s time to stop chasing industrial pipe dreams that promise a few jobs that never appear.

Like it or not, the valley is tied to globalization and decisions made half way around the world impact the Kitimat Valley.

Who knows what will happen in 2020 or 2025 when the next equivalent of a Brexit shocks the world economy?

Suppose, as some here would wish, that all the opposition to tankers and pipelines suddenly disappeared overnight. Does that mean that the projects would then go ahead?

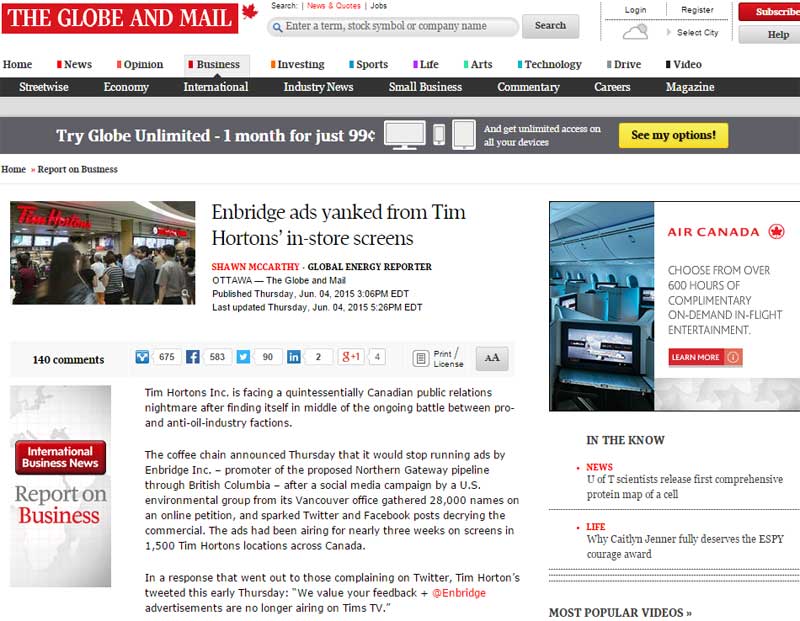

The corporate planners would decide based on their projections for the world economy and the viability of the project for their profit picture. Enbridge was never really able to secure customers for its bitumen. Chevron had no customers for Kitimat LNG. LNG Canada is a partnership, and the partner customers in Asia decided that at this time, the investment is too risky, even if LNG Canada’s longer term prospects are good.

Promoting tourism should now be the priority for Council, for Economic Development, for the Haisla Nation Council, for the local business.

Beyond tourism, it’s time for some innovative thinking to come up with other ideas that would free Kitimat from the commodity cycle. At the moment there are no ideas on the horizon, but unless everyone starts looking for new ideas, practical ideas, the commodity cycle will rule.