(First in series of reports on how the Joint Review Panel report will affect the Kitimat region)

If there is a significant flaw in the Joint Review Panel report on Northern Gateway, it can be found in the panel’s analysis of Enbridge Northern Gateway’s plans to blast and dredge at the proposed Kitimat terminal site.

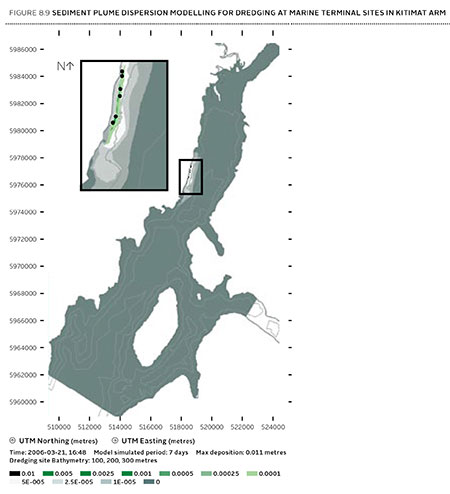

While the Joint Review Panel does consider what it calls “cumulative effects,” the panel plays down those effects and offers no specifics about interaction between the Northern Gateway project and the two liquified natural gas projects, the KM LNG project at Bish Cove and the BC LNG floating terminal at the old log dump.

It appears the JRP considered the legacy effects of the Rio Tinto Alcan smelter and other Kitimat industries while not taking into consideration future development.

The dredging and blasting planned by Northern Gateway, as Enbridge said in its evidence, appears to have only a minimal effect on Douglas Channel.

A glance at the map in the Joint Review ruling shows that that the dredging and blasting site is directly opposite Clio Bay, where Chevron, in partnership with the Haisla Nation, plan a remediation project using marine clay from the Bish Cove construction site to cap decades of sunken and rotting logs.

The Clio Bay project was not part of the evidence before the Joint Review Panel, the plans for the project were not formulated until well after the time for evidence before the JRP closed. But those deadlines show one area where the rules of evidence and procedure fail the people of northwestern BC.

The JRP is a snapshot in time and changes in the dynamics of the industrial development in the Kitimat Arm are not really considered beyond the terms of reference for the JRP.

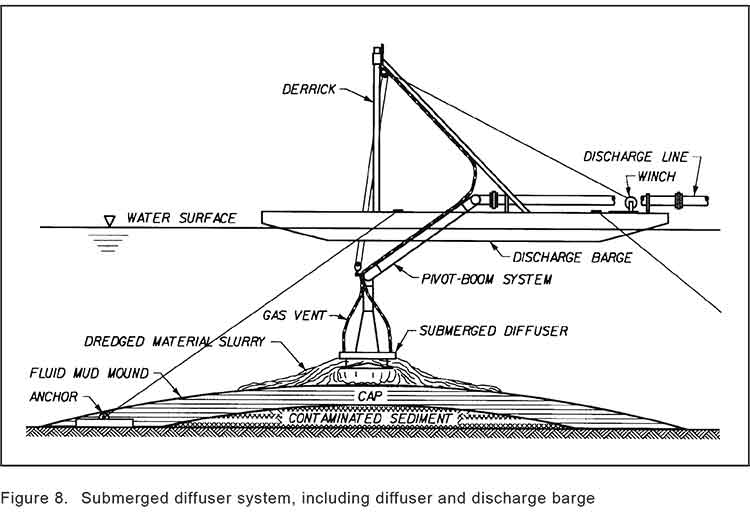

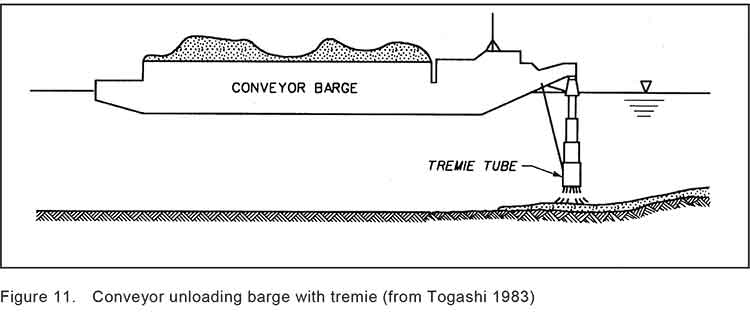

It appears from the report that Enbridge plans to simply allow sediment from the blasting and dredging to float down Douglas Channel, dispersed by the currents and the outflow from the Kitimat River.

Northern Gateway said that dredging and blasting for marine terminal construction would result in a sediment plume that would extend over an area of 70,000 square metres for the duration of blasting activities.

Approximately 400 square metres of the assessed area of the marine terminal is expected to receive more than 1 centimetre of sediment deposition due to dredging. Outside of this area, typical sediment deposition levels alongshore where sediment is widely dispersed (a band approximately 4 kilometres long and 400 metres wide) are very low; in the range of 0.001 to 0.1 centimetres. Dredging and blasting activities are expected to occur over a period of approximately 18 weeks.

Northern Gateway expected most of the sediment plume created by construction activities to be minor in relation to natural background levels.

Northern Gateway would use bubble curtains to reduce pressure and acoustic effects of blasting, and silt curtains to reduce the effect of sedimentation from dredging. It said that bubble curtains are used extensively for other activities, such as pile driving, to reduce the effect of high pressure pulses that can cause injury to fish.

It added that bubble curtains have been tested extensively with blasts, and literature shows they are effective.

Northern Gateway said that physical effects from suspended sediment on marine fish and invertebrates could include abrasion and clogging of filtration mechanisms, which can interfere with ingestion and respiration. In extreme cases, effects could include smothering, burial, and mortality to fish and invertebrates. Direct chemical-related effects of suspended sediment on organisms, including reduced growth and survival, can also occur as a result of the uptake of contaminants

re-suspended by project construction activities, such as dredging and blasting, and as a result ofstorm events, tides, and currents.

The Haisla Nation and Raincoast Conservation objected to Northern Gateway’s figures, noting

Northern Gateway’s sediment and circulation model and its evidence related to contaminated sediment re-suspension at the terminal site. Both parties said that the sediment model was applied for the spring, when the increase in total suspended solids would be negligible compared to background values. In the event of delays, blasting and dredging would likely occur at other times of the year when effects would likely be higher, and these scenarios were not modelled.

The panel’s assessment of the area to be blasted found few species:

Species diversity within Kitimat Arm’s rocky intertidal community is generally low. Barnacles, mussels, periwinkles, and limpets can be found on rocky substrate. Sea urchins, moon snails, sea anemones, sea stars, and sea cucumbers are in shallow subtidal areas. Sandy areas are inhabited by commercially-harvested bivalves such as butter clams and cockles.

Northern Gateway told the JRP that it would “offset” any damage to Douglas Channel caused by the blasting and dredging

Northern Gateway said that construction, operations, and decommissioning of the marine terminal would result in both permanent and temporary alteration of marine fish habitat. Dredging and blasting, and installing physical structures in the water column for the marine terminal would permanently alter marine fish habitat. Based on the current terminal design, in-water site preparation would result in the physical alteration of approximately 1.6 hectares of subtidal marine habitat and 0.38 hectares of intertidal marine habitat. Northern Gateway expected approximately 353 square metres of subtidal marine habitat and 29 square metres of intertidal habitat to be permanently lost.This habitat would be compensated for by marine habitat offsets.

The project’s in-water vertical structures that would support the mooring and berthing structures could create new habitat, offsetting potential adverse effects. The structures may act as artificial reefs, providing marine fish habitat, food, and protection from predation. Although organisms currently inhabiting the work area would be killed, the exposed bedrock would be available for colonization as soon as the physical works are completed.

In its finding on marine sediment, the panel, as it does throughout the ruling, believes that the disruption to the environment caused by previous and ongoing human activity, means that the Northern Gateway Kitimat terminal won’t make that much difference.

Sediment quality in the marine environment is important because sediment provides habitat for benthic aquatic organisms. Northern Gateway’s baseline data for the area immediately surrounding the marine terminal indicated some contamination of water, sediments, and benthic organisms from previous industrial activity. Industrial activities in the Kitimat area have released contaminants through air emissions and effluent discharges since the 1960s. Sources of contaminants to Kitimat Arm

include effluent from a municipal wastewater treatment plant, the Alcan smelter, Methanex Corporation’s methanol plant, and the Eurocan pulpmill, as well as storm water runoff from these operations and the municipality.Area is largely controlled by natural outflow from the Kitimat River with suspended sediment levels being highest during peak river runoff (May to July, and October) and lowest during winter. Storm events, tides, and currents can also suspend sediments. Levels of total suspended solids fluctuate seasonally and in response to climatic variations, but are generally highest during the summer.

Commercial and recreational vessels currently operating in the area may increase suspended solids by creating water turbulence that disturbs sediments. Given the current sediment contamination levels and the limited area over which sedimentation from construction activities would be expected to disperse, the Panel finds that the risk posed by disturbed contaminated sediment is low. Northern Gateway has committed to monitoring during construction to verify the predicted effects on sediment and water quality for both contaminants and total suspended solids..

The dredging and blasting section of the Joint Review Report is small when compared to the much more extensive sections on pipeline construction and tanker traffic, and the possible effects of a catastrophic oil spill.

Although minor, the marine sediment section exposes the question that was never asked, given the disruptions from years of log dumping at Clio Bay and Minette Bay and the decades of developments at the mouth of the Kitimat River, and future development from LNG, when do cumulative effects begin to overwhelm? How much is enough? How much is too much? If every project continues to be viewed in isolation, what will be left when every project is up and running?