There’s one question about the Enbridge Northern Gateway project that many people ask and few can answer: Who is responsible for the port of Kitimat? Who would be liable should there be a disaster in the port? Nobody really knows.

Unlike many harbours in Canada, the port of Kitimat is “private,” although as the District of Kitimat says, “Transport Canada and other federal agencies continue to regulate navigation, security and environmental safety.” Kitimat has promoted that private status as an economic advantage.

If there’s a dispute, the question of responsibility and liability would probably end up in the Supreme Court of Canada, with the justices sorting out a historic puzzle. Or perhaps that historical puzzle could mean that the future of the port of Kitimat might be decided by the next B.C. provincial election.

Most of the other harbours in Canada are the responsibility of Ports Canada, a branch of Transport Canada or run by (usually not-for-profit) semi-public port corporations or local harbour commissions.

To find out why Kitimat is one of the few private ports in Canada, the first thing to do is watch Eliza Kazan and Bud Schulberg’s classic 1954 multiple Oscar winning movie, On the Waterfront, starring Marlon Brando, about how the mob ran the New York docks.

What has On the Waterfront got to do with Kitimat? It goes back to when the then Aluminum Company of Canada/Alcan (now Rio Tinto Alcan) was planning the Kitimat project; much of that work was done in New York both by employees and consultants. It was in 1949, that Malcolm Johnson, a New York Sun reporter, wrote a Pulitzer Prize winning series of investigative reports called “Crime on the Waterfront,” exposing corruption and Mafia involvement with the docks and the longshoremans’ union. The movie was based, in part, on that investigative series.

So in its planning, Alcan was determined that the longshore unions would not be involved in running the docks in Kitimat. The publicly stated reason has always been that Alcan wanted a seamless 24/7 operation that would be integrated with the aluminum smelter. Alcan would sign a collective agreement with the United Steelworkers that covered both the smelter and the docks. (CAW 2301 now represents most of the workers at the Kitimat smelter.)

When the Kitimat project was being finalized in 1949 and 1950 at the height of the Cold War, aluminum was a strategic commodity, security was high on the agenda, and it was not just the Soviet bloc but the mob as well that worried the authorities.

Add two factors. First, in 1949 the province of British Columbia was anxious to promote what would today be called a “mega-project.” Second, in the post-war era when corporations were relatively enlightened compared to today, Alcan was determined not to create the traditional “company town.”

To promote private-sector development of both hydro-electricity and aluminum, B.C. signed a rather loosely worded agreement with Alcan, noting that the project was going on “without investment by or risk to the government.” That agreement was implemented by the Legislative Assembly of B.C. by an equally wide open Industrial Development Act. One aim of both was try to ensure that future “socialists” would not expropriate the project.

Industrial township

With the province handing over the Crown land at the head of Douglas Channel at a very nominal price to Alcan, next came the creation of the District of Kitimat. With the town under construction, with few buildings and a small population, under normal B.C. practice, the area would be “unincorporated” and would not have a municipal government. But Alcan and the province came up with a new concept, which they called “an industrial township,” which would allow a municipal government to be established in anticipation of future growth.

The act that established the District of Kitimat put the boundaries outside the land owned by Alcan (excluding land reserved for the Haisla Nation).

Alcan began selling off the land in the planned areas of the town and other land it didn’t need. Individuals bought houses and businesses bought the land for their own use. Alcan retained ownership of the harbour and estuary lands and the small “Hospital Beach.”

The District of Kitimat has some legal responsibility for “wharfs” at the port of Kitimat. At council meetings, the environmental group, Douglas Channel Watch, has raised the question of the district’s responsibility and liability in case of an Enbridge incident but there’s been no definitive response from district staff. There is no municipal harbour commission as there is in other jurisdictions.

Up until recently, it was a convenient arrangement for everyone involved. Alcan, Eurocan and Methanex ran their dock operations without any interference, beyond standard Transport Canada oversight.

Things began to change in 2007, when the Rio Tinto Group bought Alcan, creating Rio Tinto Alcan. A couple of years ago, a senior staff source in the Canadian Auto Workers explained it to me it this way. “Alcan was a big corporation, but Alcan was a corporation with a big stake in Canada. As a union, we could do business with them. Rio Tinto is a transnational corporation with businesses in lots of countries but no stake in any of them. So it’s a lot harder now.”

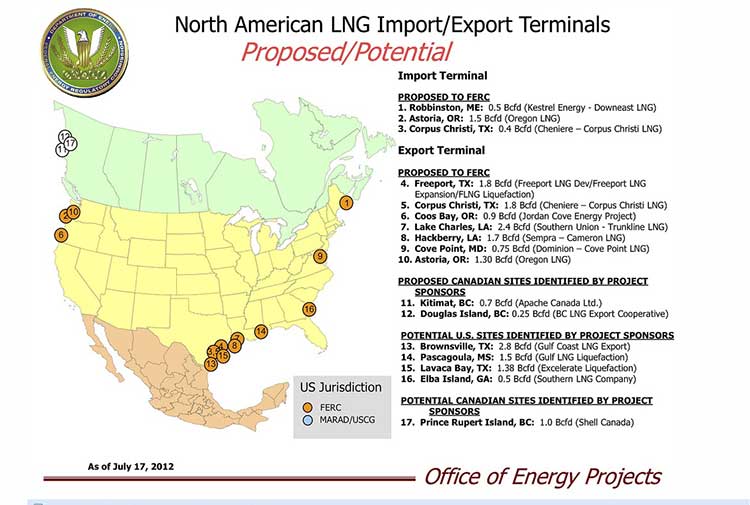

With the Rio Tinto acquisition of Alcan, things tightened up in Kitimat. Negotiations between the District and RTA for the District to obtain more land stalled. Access to the estuary and other RTA lands that had been somewhat open under Alcan became more restrictive. In 2010, the Eurocan paper mill shut down along with its dock. In 2011, Rio Tinto bought the dock from West Fraser, owner of Eurocan. The Kitimat community noted that when the dock was repainted, it said just “Rio Tinto.” not “Rio Tinto Alcan” and that led to lots of gossip and wondering about what the Rio Tinto Group really plans for Kitimat. Last fall, Shell Canada purchased the former Methanex dock for part of its liquified natural gas operations.

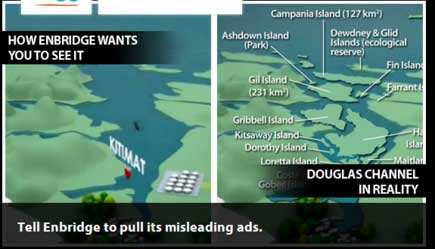

With the Enbridge Northern Gateway project, the BC LNG project at North Cove and the KM LNG project at Bish Cove all along the shore of Douglas Channel and within the boundaries of the District of Kitimat which extends as far south as Jesse Lake, the question that has to be asked is, what happens now? If the Enbridge project is built, it will start just beyond the boundaries of the land owned by Rio Tinto Alcan.

That old arrangement between Alcan and the District of Kitimat is facing many new challenges.

The district once had a harbour master, but the position was eliminated because he had nothing to do. Alcan owned its docks, Alcan managed the docks and Alcan union employees worked on the docks. Later came the Eurocan (now owned by Rio Tinto) and Methanex (now owned by Shell) docks, again owned and operated by private corporations.

The District of Kitimat, nominally in charge, was content to sit back and collect taxes.

With the Enbridge Northern Gateway project, the B.C. LNG project at North Cove and the KM LNG project at Bish Cove all along the shore of Douglas Channel and within the boundaries of the District of Kitimat, the question that has to be asked is, what happens now? If the Enbridge project is built, it will start just beyond the boundaries of the land owned by Rio Tinto Alcan.

In Canada, ports and harbours are normally under federal jurisdiction and Transport Canada has oversight. But Alcan’s “private port” and the District of Kitimat were created by acts passed by the B.C. government.

The original agreement between the province and Alcan mentions an “aluminum plant” and “low-cost electrical power,” it doesn’t mention bitumen or liquified natural gas. Those provincial acts do not cover bitumen, supertankers and liquified natural gas.

B.C. Opposition Leader Adrian Dix has made it clear that his New Democratic Party opposes the Northern Gateway project. The federal government has said the province can’t really do anything to stop Enbridge Northern Gateway once Stephen Harper has decided that the pipeline project is in the national interest.

At this moment, Dix is a “contender” for the premiership, with Christy Clark and the B.C. Liberals dropping in the polls and with key members of her government deciding not to run in the election next spring.

So, if, as expected, Adrian Dix becomes the next B.C. premier, he has one very strong hand to play. Any act can, with proper legal advice, be amended by the B.C. legislature. That means the “socialists” so feared by Alcan and the premier of the day, Byron “Boss” Johnson, could alter the 1949 law. That in turn may upset the decades-old arrangement that created the private port which Enbridge is banking on.