The United States says acidification of the oceans means there is an already growing risk to the northwest coast fishery, including crab and salmon, according to studies released by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

As more carbon dioxide is released into the atmosphere and absorbed by the oceans, the water is becoming more acidic and that affects many species, especially shellfish, dissolving the shells.

A NOAA study released today of environmental and economic risks to the Alaska fishery says:

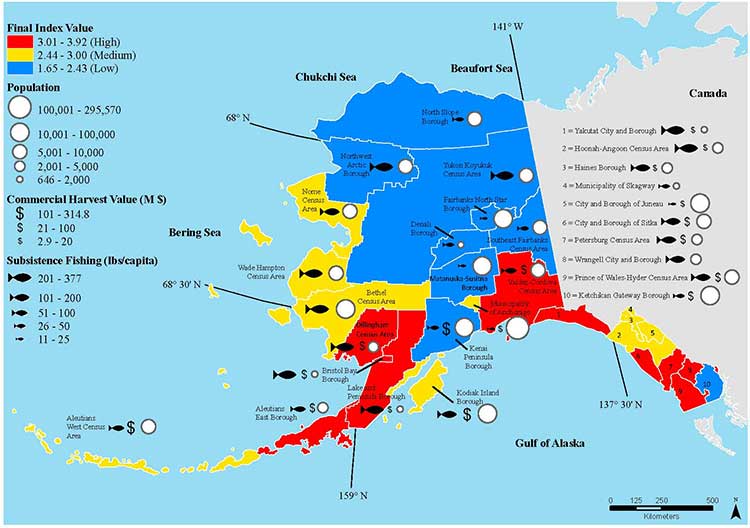

Many of Alaska’s nutritionally and economically valuable marine fisheries are located in waters that are already experiencing ocean acidification, and will see more in the near future…. Communities in southeast and southwest Alaska face the highest risk from ocean acidification because they rely heavily on fisheries that are expected to be most affected by ocean acidification…

An earlier NOAA study, released in April, identified a long term threat to the salmon fishery as small ocean snails called pteropods which are a prime food source for pink salmon are already being affected by the acidification of the ocean.

NOAA says:

The term “ocean acidification” describes the process of ocean water becoming more acidic as a result of absorbing nearly a third of the carbon dioxide released into the atmosphere from human sources. This change in ocean chemistry is affecting marine life, particularly the ability of shellfish, corals and small creatures in the early stages of the food chain to build skeletons or shells.

Today’s NOAA study is the first published research by the Synthesis of Arctic Research (SOAR) program, which is supported by an US inter-agency agreement between NOAA’s Office of Oceanic and Atmospheric Research and the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) Alaska Region.

Canada’s Department of Fisheries and Oceans says it has ongoing studies on oceanic acidification including the role of petropods in the lifecycle of the salmon.

Des Nobles, President of Local #37 Fish [UFAWU-UNIFOR] told Northwest Coast Energy News that the fisheries union and other fisheries groups in Prince Rupert have asked both the Canadian federal and the BC provincial governments for action on ocean acidification. Nobles says so far those requests have been ignored,

Threat to crabs

The studies show that red king crab and tanner crab grow more slowly and don’t survive as well in more acidic waters. Alaska’s coastal waters are particularly vulnerable to ocean acidification because of cold water that can absorb more carbon dioxide and unique ocean circulation patterns which bring naturally acidic deep ocean waters to the surface.

“We went beyond the traditional approach of looking at dollars lost or species impacted; we know these fisheries are lifelines for native communities and what we’ve learned will help them adapt to a changing ocean environment,” said Jeremy Mathis, Ph.D., co-lead author of the study, an oceanographer at NOAA’s Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory in Seattle, and the director of the University of Alaska Fairbanks School of Fisheries and Ocean Sciences Ocean Acidification Research Center.

As for Dungeness crab, Sarah Cooley, a co-author of the Alaska study, who was with the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution at the time, told Northwest Coast Energy News, “The studies have not been done for Dungeness crab that have been done for king and tanner crab, that’s something we’re keenly aware of. There’s a big knowledge gap at this point.” She says NOAA may soon be looking at pilot study on Dungeness crab.

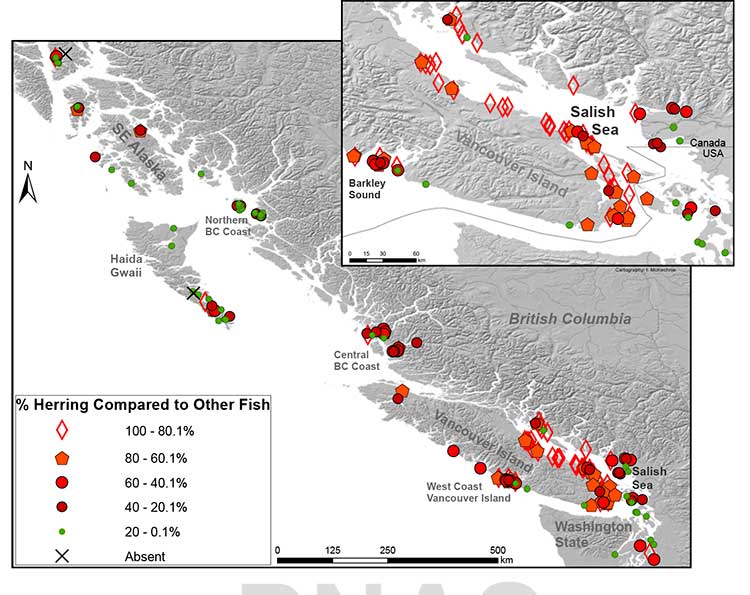

Risk to Salmon, Mackerel and Herring

In a 2011-2013 survey, a NOAA-led research team found the first evidence: “that acidity of continental shelf waters off the West Coast is dissolving the shells of tiny free-swimming marine snails, called pteropods, which provide food for pink salmon, mackerel and herring.”

The survey estimated that the percentage of pteropods along the west coast with dissolving shells due to ocean acidification had “doubled in the near shore habitat since the pre-industrial era and is on track to triple by 2050 when coastal waters become 70 percent more corrosive than in the pre-industrial era due to human-caused ocean acidification.”

That study documented the movement of corrosive waters onto the continental shelf from April to September during the upwelling season, when winds bring water rich in carbon dioxide up from depths of about 120 to 180 metres to the surface and onto the continental shelf.

“We haven’t done the extensive amount of studies yet on the young salmon fry,” Cooley said. “I would love to see those studies done. I think there is a real need for that information. Salmon are just so so important for the entire Pacific Northwest and up to Alaska.”

In Prince Rupert, Barb Faggetter, an independent oceanographer whose company Ocean Ecology has consulted for the fisherman’s union and NGOs, who was not part of the study, spoke generally about the threat of acidification to the region.

She is currently studying the impact of the proposed Liquified Natural Gas terminals that could be built at Prince Rupert near the Skeena River estuary. Faggetter said that acidification could affect the species eaten by juvenile salmon. “As young juveniles they eat a lot of zooplankton including crustaceans and shell fish larvae.”

She added, “Any of the shell fish in the fishery, including probably things like sea urchins are all organisms that are susceptible to ocean acidification because of the loss of their capacity to actually incorporate calcium carbonate into their shells.”

Faggetter said her studies have concentrated on potential habitat loss near Prince Rupert as a result of dredging and other activities for liquified natural gas development, She adds that ocean acidification “has been a consideration that climate change will further worsen any potential damage that we’re currently looking at.”

Her studies of the Skeena estuary are concentrating on “rating” areas based on the food supply available to juvenile salmon, as well as predation and what habitat is available and the quality of that habitat to identify areas that “are most important for the juvenile salmon coming out of the Skeena River estuary and which are less important.”

She said that climate change and ocean acidification could impact the Skeena estuary and “probably reduce some of the environments that are currently good because they have a good food supply. If ocean acidification reduces that food supply that will no longer be good habitat for them” [juvenile salmon].

The August 2011 NOAA survey of the pteropods was done at sea using “bongo nets” to retrieve the small snails at depths up to 200 metres. The research drew upon a West Coast survey by the NOAA Ocean Acidification Program in that was conducted on board the R/V Wecoma, owned by the National Science Foundation and operated by Oregon State University.

The DFO study, according to the agency website is “being examined in the context of model predictions.”

Nina Bednarsek, Ph.D., of NOAA’s Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory in Seattle, the lead author of the April pteropod paper said, “Our findings are the first evidence that a large fraction of the West Coast pteropod population is being affected by ocean acidification.

“Dissolving coastal pteropod shells point to the need to study how acidification may be affecting the larger marine ecosystem. These near shore waters provide essential habitat to a great diversity of marine species, including many economically important fish that support coastal economies and provide us with food.”

Ecology and economy

Today’s study on the effects of acidification on the Alaska fishery study examined the potential effects on a state where the fishing industry supports over 100,000 jobs and generates more than $5 billion in annual revenue. Fishery-related tourism also brings in $300 million annually to the state.

The study also shows that approximately 120,000 people or roughly 17 percent of Alaskans rely on subsistence fisheries for most, if not all of their dietary protein. The Alaska subsistence fishery is open to all residents of the state who need it, although a majority of those who participate in the subsistence fishery are Alaska’s First Nations. In that way it is somewhat parallel to Canada’s Food, Ceremonial and Social program for First Nations.

“Ocean acidification is not just an ecological problem—it’s an economic problem,” said Steve Colt, Ph.D., co-author of the study and an economist at the University of Alaska Anchorage. “The people of coastal Alaska, who have always looked to the sea for sustenance and prosperity, will be most affected. But all Alaskans need to understand how and where ocean acidification threatens our marine resources so that we can work together to address the challenges and maintain healthy and productive coastal communities.”

The Alaska study recommends that residents and stakeholders in vulnerable regions prepare for environmental challenge and develop response strategies that incorporate community values and needs.

“This research allows planners to think creatively about ways to help coastal communities withstand environmental change,” said Cooley, who is now science outreach manager at Ocean Conservancy, in Washington, D.C. “Adaptations can be tailored to address specific social and environmental weak points that exist in a community.

“This is really the first time that we’ve been able to go under the hood and really look at the factors that make a particular community in a borough or census are less or more vulnerable from changing conditions resulting from acidification. It gives us a lot of power so that we don’t just look at environmental issues but also look at the social story behind that risk.”

As for the southern part of the Alaska panhandle nearest British Columbia, Cooley said, “What we found is that there is a high relative risk compared to some of the other areas of Alaska and that is because the communities there undertake a lot of subsistence fishing, There tend not be a whole lot of commercial harvests in the fisheries there but they are very very important from a subsistence stand point… And they’re tied to species that we expect to be on the front line of acidification, many of the clam species that are harvested in that area and some of the crab species.”

Long term effects

Libby Jewett, Director of the NOAA Ocean Acidification Program and author of the pteropod study said, “Acidification of our oceans may impact marine ecosystems in a way that threatens the sustainability of the marine resources we depend on.

“Research on the progression and impacts of ocean acidification is vital to understanding the consequences of our burning of fossil fuels.”

“Acidification is happening now,” Cooley said. “We have not yet observed major declines in Alaskan harvested species. In Washington and Oregon they have seen widespread oyster mortality from acidification.

“We don’t have the documentation for what’s happening in Alaska right now but there are a lot of studies staring up right now that will just keep an eye out for that sort of thing, Acidification is going to be continuing progressively over the next decades into the future indefinitely until we really curb carbon dioxide emissions. There’s enough momentum in the system that is going to keep acidification advancing for quite some time.

“What we need to be doing as we cut the carbon dioxide, we need to find ways to strength communities that depend on resources and this study allows us to think differently about that and too really look at how we can strengthen those communities.

Faggetter said. “It’s one more blow to an already complex situation here, My study has been working particularly on eel grass on Flora Bank (pdf) which is a very critical habitat, which is going to be impacted by these potential industrial developments and that impact will affect our juvenile salmon and our salmon fishery very dramatically, that could be further worsened by ocean acidification.”

She said that acidification could also be a long term threat to plans in Prince Rupert to establish a geoduck fishery (pronounced gooey-duck).

The popular large 15 to 20 centimetre clam is harvested in Washington State and southern BC, but so far hasn’t been subject to commercial fishing in the north.

NOAA said today’s study shows that by examining all the factors that contribute to risk, more opportunities can be found to prevent harm to human communities at a local level. Decision-makers can address socioeconomic factors that lower the ability of people and communities to adapt to environmental change, such as low incomes, poor nutrition, lack of educational attainment and lack of diverse employment opportunities.

NOAA’s Ocean Acidification Program and the state of Alaska are also developing tools to help industry adapt to increasing acidity.

The new NOAA study is the first published research by the Synthesis of Arctic Research (SOAR) program. which is supported by an inter-agency agreement between NOAA’s Office of Oceanic and Atmospheric Research and the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) Alaska Region.

The pteropod study was published in April in Proceedings of the Royal Society B. The ecological and economic study is published in Progress in Oceanography.