Special report: Clio Bay cleanup: Controversial, complicated and costly

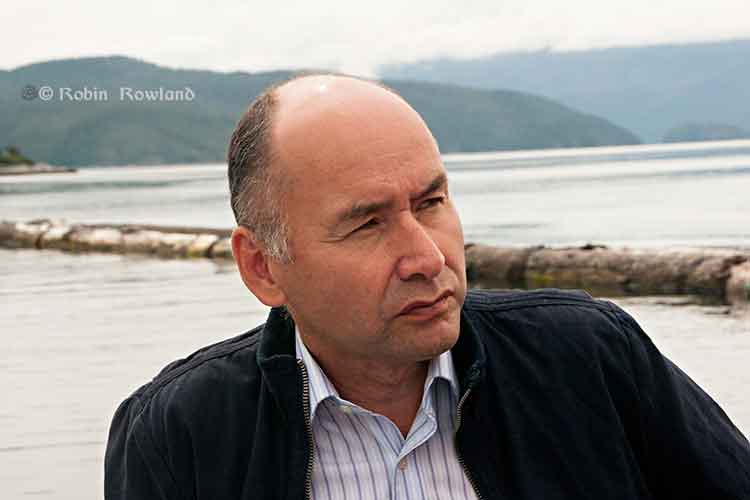

Haisla First Nation Chief Counsellor Ellis Ross says the Haisla made the proposal to the KM LNG project, a partnership of Chevron and Apache, to use the marine clay to cover the thousands of logs at the bottom of Clio Bay after years frustration with the Department of Fisheries and Oceans and the BC provincial government, which for decades ignored requests for help in restoring almost fifty sunken log sites in Haisla traditional territory.

The problem is that remediation of the hundreds of sites on Canada’s west coast most containing tens of thousands of sunken logs has been so low on DFO’s priority list that even before the omnibus bills that gutted environmental protection in Canada, remediation of sunken log sites by DFO could be called no priority.

Now that the KM LNG has to depose of a total of about 3.5 million cubic metres of marine clay and possibly other materials from the Bish Cove site, suddenly log remediation went to high priority at DFO.

The controversy is rooted in the fact that although the leaders of the Haisla and the executives at Chevron knew about the idea of capping Clio Bay, people in the region, both many residents of Kitimat and some members of the Haisla were surprised when the project was announced in the latest KM LNG newsletter distributed to homes in the valley.

Chevron statement

In a statement sent to Northwest Coast Energy News Chevron spokesperson Gillian Robinson Ridell said:

The Clio Bay Restoration Project proposed by Chevron, is planned to get underway sometime in early 2014. The proposal is fully supported by the Federal Department of Fisheries and Oceans and the Haisla First Nation Council. The project has been put forward as the best option for removal of the marine clay that is being excavated from the Kitimat LNG site at Bish Cove. Chevron hired Stantec, an independent engineering and environmental consulting firm with extensive experience in many major habitat restoration projects that involve public safety and environmental conservation. The Haisla, along with Stantec’s local marine biologists, identified Clio Bay as a site that has undergone significant environmental degradation over years of accumulation of underwater wood debris caused by historic log-booming operations. The proposal put forward by the marine biologists was that restoration of the marine ecosystem in the Bay could be achieved if marine clay from Chevron’s facility site, was used to cover the woody debris at the bottom of the Bay. The process outlined by the project proposal is designed to restore the Clio Bay seafloor to its original soft substrate that could sustain a recovery of biological diversity.

Kitimat worried

Non-aboriginal residents of Kitimat are increasingly worried about being cut off from both Douglas Channel and the terrestrial back country by industrial development. These fears have been heightened by reports that say that Clio Bay could be closed to the public for “safety reasons” for as much as 16 months during the restoration project.

The fact that Clio is known both as a safe anchorage during bad weather and an easy to get to location for day trips from Kitimat has made those worries even more critical.

There is also a strong feeling in Kitimat that the residents were kept out of the loop when it came to the Clio Bay proposal.

In a letter to the District of Kitimat, DFO said:

Clio Bay has been used as a log handling site for decades which has resulted in areas of degraded habitat from accumulations of woody debris materials on the sea floor. The project intends to cap impacted areas with inert materials and restore soft substrate seafloor. The remediation of the seafloor is predicted to enhance natural biodiversity and improve the productivity of the local fishery for Dungeness crab. The project area does support a variety of life that will be impact and therefore the project will require authorization from Fisheries and Oceans Canada for the Harmful Alteration, Disruption or Destruction (HADD) of fish and fish habitat.

The letter avoids the controversy over the use of marine clay but saying “inert material” will be used. That can only increase the worries from residents who say that not only clay but sand, gravel and other overburden from Bish Cove and the upgrade of the Forest Service Road may be used in Clio Bay. (The use of “inert material” also gives DFO an out if it turns out the department concludes the usual practice of using sand is better. That, of course, leaves the question of what to do with the clay).

Although Ellis Ross has said he wants to see large numbers of halibut and cod return to Clio Bay, the DFO letter only mentions the Dungeness Crab.

Try to search “remediation” on the DFO site and the viewer is redirected to a page that cites the omnibus bills passed by the Conservative government and says

On June 29, 2012, the Fisheries Act was amended. Policy and regulations are now being developed to support the new fisheries protection provisions of the Act (which are not yet in force). The existing guidance and policies continue to apply. For more information, see Changes to the Fisheries Act.

On April 2nd, 2013 the Habitat Management Program’s name was changed to the Fisheries Protection Program.

So, despite what communications officers for DFO and the Harper government may say, there was no policy then and there is no policy now on remediation of log sites. Given Harper’s attitude that LNG and possibly bitumen export must proceed quickly with no environmental barriers, it is likely that environmental remediation will continue to be no priority—unless remediation becomes a problem that the energy giants have to solve and pay for.

Alaska studies

On the other hand, the State of Alaska and the United States Environmental Protection Agency spent a decade at a site near Ketchikan studying the environmental problems related to sunken logs at transfer sites

Those studies led Alaska to issue guidelines in 2002 with recommended practices for rehabilitating ocean log dump sites and for the studies that should precede any remediation project.

The Alaska studies also show that in Pacific northwest coast areas, the ecological effects of decades of log dumping, either accidental or deliberate, vary greatly depending on the topography of the region, the topography of the seabed, flow of rivers and currents as well as industrial uses along the shoreline.

The Alaska policy is based on studies and a remediation project at Ward Cove, which in many ways resembles Clio Bay, not far from Kitimat, near Ketchikan.

The Alaska policy follows guidelines from both the US Environmental Protection Agency and the US Army Corps of Engineers that recommend using thin layers of “clean sand” as the best practice method for capping contaminated sites. (The Army Corps of Engineers guidelines say that “clay balls” can be used to cap contaminated sites under some conditions. Both a spokesperson for the Corps of Engineers and officials at the Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation told Northwest Coast Energy News that they have no records or research on using marine clay on a large scale to cap a site.)

The EPA actually chose Sechelt, BC, based Construction Aggregates to provide the fine sand for the Ward Cove remediation project. The sand was loaded onto 10,000 tonne deck barges, hauled up the coast to Ward Cove, offloaded and stockpiled then transferred to derrick barges and carefully deposited on the sea bottom using modified clam shell buckets.

The EPA says

Nearly 25,000 tons of sand were placed at the Ward Cove site to cap about 27 acres of contaminated sediments and 3 other acres. In addition, about 3 acres of contaminated sediments were dredged in front of the main dock facility and 1 acre was dredged near the northeast corner of the cove. An additional 50 acres of contaminated sediments have been left to recover naturally.

A report by Integral Consulting, one of the firms involved at the project estimated that 17,800 cubic metres of sand were used at Ward Cove.

In contrast, to 17,800 cubic metres of sand used at Ward Cove, the Bish Cove project must dispose of about 1.2 million cubic metres of marine clay at sea (with another 1.2 million cubic metres slated for deposit in old quarries near Bees Creek).

Studies at Ward Cove began as far back as 1975. In 1990 Alaska placed Ward Cove on a list of “water-quality limited sites.” The studies intensified in 1995 after the main polluter of Ward Cove, the Ketchikan Paper Company, agreed in a consent degree on a remediation plan with the Environmental Protection Agency in 1995. After almost five years of intensive studies of the cove, the sand-capping and other remediation operations were conducted from November 2000 to March 2001. A major post-remediation study was carried out at Ward Cove in 2004 and again in 2009. The next one is slated for 2015.

Deaf ears at DFO

“We need to put pressure on the province or Canada to cleanup these sites. We’ve been trying to do this for the last 30 years. We got nowhere,” Ellis Ross says. “Before when we talked [to DFO] about getting those logs and cables cleaned up, it fell on deaf ears. They had no policy and no authority to hold these companies accountable. So we’re stuck, we’re stuck between a rock and hard place. How do we fix it?”

Ross says there has been one small pilot project using marine clay for capping which the Haisla’s advisers and Chevron believe can be scaled up for Clio Bay.

Douglas Channel studies

The one area around Kitimat that has been studied on a regular basis is Minette Bay. The first study occurred in 1951, before Alcan built the smelter and was used as a benchmark in future studies. In 1995 and 1996, DFO studied Minette Bay and came to the conclusion that because the water there was so stagnant, log dumping there had not contributed to low levels of dissolved oxygen although it said that it could not rule out “other deleterious effects on water quality and habitat`from log dumping.”

That DFO report also says that there were complaints about log dumping at Minette Bay as far back as 1975, which would tend to confirm what Ross says, that the Haisla have been complaining about environmentally degrading practices for about 30 years.

Ross told Northwest Coast Energy News that if the Clio Bay remediation project is successful, the next place for remediation should be Minette Bay.

A year after the Minette Bay study, DFO did a preliminary study of log transfer sites in Douglas Channel, with an aerial survey in March 1997 and on water studies in 1998. The DFO survey identified 52 locations with sunken logs on Douglas Channel as “potential study sites.” That list does not include Clio Bay. On water studies were done at the Dala River dump site at the head of the inlet on Kildala Arm, Weewanie Hotsprings, at the southwest corner of the cove, the Ochwe Bay log dump where the Paril River estuary opens into the Gardner Canal and the Collins Bay log dump also on the Gardner Canal.

In the introduction to its report, published in 2000, the DFO authors noted “the cumulative effect of several hundred sites located on BC coast is currently unknown.”

DFO list of sunken log sites on Douglas Channel (pdf)

Since there appears to have been no significant follow-up, that cumulative effect is still “unknown.”

In 2000 and 2001, Chris Picard, then with the University of Victoria, now Science Director for the Gitga’at First Nation did a comparison survey of Clio Bay and Eagle Bay under special funding for a “Coasts Under Stress” project funded by the federal government. Picard’s study found that Eagle Bay, where there had been no log dumping was in much better shape than Clio Bay. For example, Picard’s study says that “Dungeness crabs were observed five times more often in the unimpacted Clio Bay.”

Although low oxygen levels have been cited as a reason for capping Clio Bay, Picard’s study says that “near surface” oxygen levels “did not reliably distinguish Clio and Eagle Bay sediments.” While Clio Bay did show consistent low oxygen levels, Eagle Bay showed “considerable interseasonal variation” which is consistent with the much more intensive and ongoing studies of oxygen levels at Wards Cove.

Chevron’s surprise

It appears that Chevron was taken by surprise by the controversy over the Clio Bay restoration. Multiple sources at the District of the Kitimat have told Northwest Coast Energy News that in meetings with Chevron, the company officials seemed to be scrambling to find out more about Clio Bay.

This is borne out by the fact, in its communications with Northwest Coast Energy News, Chevron says its consulting firm, Stantec has cited just two studies, Chris Picard’s survey of Clio Bay and a 1991 overview of log-booming practices on the US and Canadian Pacfic coasts. So far, Chevron has not cited the more up-to-date and detailed studies of Ward Cove that were conducted from 1995 to 2005.

Chevron says that Stantec marine biologists are now conducting extensive field work using divers and Remote Operated Vehicle surveys to “observe and record all flora and fauna in the bay and its levels of abundance. Stantec’s observations echoed the previous studies which determined that the massive amount of wood has harmed Clio Bay’s habitat and ecosystem.”

In its statement to Northwest Coast Energy News, Chevron cited its work on Barrow Island, in Western Australia, where the Chevron Gordon LNG project is on the same island as a highly sensitive ecological reserve. Chevron says the Australian site was chosen only after a thorough assessment of the viability of other potential locations, and after the implementation of extensive mitigation measures, including a vigorous quarantine program for all equipment and materials brought on to the Barrow island site to prevent the introduction of potentially harmful alien species.

Reports in the Australian media seem to bare out Chevron’s position on environmental responsibility. Things seem to be working at Barrow Island.

Robinson went on to say:

Those same high environmental standards are being applied to the Kitimat LNG project and the proposed Clio Bay Restoration project. The proposed work would be carried out with a stringent DFO approved operational plan in place and would be overseen by qualified environmental specialists on-site.

The question that everyone in the Kitimat region must now ask is just how qualified are the environmental specialists hired by Chevron and given staff and budget cuts and pressure from the Prime Minister’s Office to downgrade environmental monitoring just how stringent will DFO be monitoring the Clio Bay remediation?

| Alaska standardsIn the absence of comprehensive Canadian studies, the only benchmark available is that set by Alaska which calls for:Capping material, typically a clean sand, or silty to gravelly sand, is placed on top of problem sediments. The type of capping material that is appropriate is usually determined during the design phase of the project after a remediation technology has been selected. Capping material is usually brought to the site by barge and put in place using a variety of methods, depending on the selected remedial action alternative.

Thick Capping Thick capping usually requires the placement of 18 to 36 inches of sand over the area. The goal of thick capping is to isolate the bark and wood debris and recreate benthic habitat that diverse benthic infauna would inhabit. Thin Capping Thin capping requires the placement of approximately 6 – 12 inches of sand on the project area. It is intended to enhance the bottom environment by creating new mini-environments, not necessarily to isolate the bark and wood debris. With thin capping, surface coverage is expected to vary spatially, providing variable areas of capped surface and amended surface sediment (where mixing between capping material and problem sediment occurs) as well as limited areas where no cap is evident. Mounding Mounding places small piles of sand or gravel dispersed over the waste material to create habitat that can be colonized by organisms. Mounding can be used where the substrate will not support capping. |

[rps-include post=5057]