Excerpts from the Northern Gateway Joint Review Panel report relating to the Exxon Valdez disaster.

Northern Gateway told the Joint Reivew Panel that

on a worldwide basis, all data sets show a steady reduction in the number

and size of oil spills since the 1970s. This decline has been even more apparent since regulatory changes in 1990 following the Exxon Valdez oil spill, which required a phase-in of double-hulled tankers in the international fleet. No double-hulled tanker has sunk since 1990. There have been five incidents of double-hulled tankers that have had a collision or grounding that penetrated the cargo tanks. Resulting spills ranged from 700 to 2500 tonnes

The Haisla countered by saying:

The Haisla Nation said that, although there have been no major spills since the Exxon Valdez spill in Prince William Sound, there were 111 reported incidents involving tanker traffic in Prince William Sound between 1997 and 2007. The three most common types of incidents were equipment malfunctions, problems with propulsion, steering, or engine function, and very small spills from tankers at berth at the marine terminal. The Haisla Nation said that, in the absence of state-of-the-art

prevention systems in Prince William Sound, any one of those incidents could have resulted in major vessel casualties or oil spills.

There were disputes about how the Exxon Valdez affected species in the Prince William Sound area:

Northern Gateway said that, although crabs are known to be sensitive to toxic effects, they have been shown to recover within 1 to 2 years following

a spill such as the Exxon Valdez incident. Northern Gateway said that Dungeness crab was a key indicator species in its assessment of spill effects.

Northern Gateway said that potential effects to razor clams are not as well studied. It said that sediment toxicity studies after the Exxon Valdez spill did not suggest significant effects on benthic invertebrates. Following the Exxon Valdez and

Selendang Ayu oil spills in Alaska, food safety closures for species such as mussels, urchins, and crabs were lifted within 1 to 2 years following the

spill.

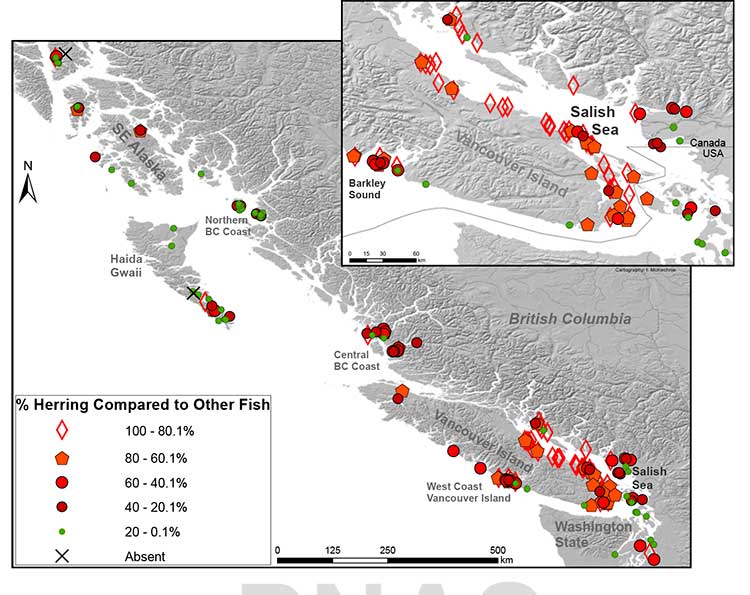

In response to questioning from the Council of the Haida Nation regarding potential spill effects on herring, Northern Gateway said that herring were a key indicator species in its spill assessment.

Northern Gateway said that the Exxon Valdez spill did not appear to cause population-level effects on Prince William Sound herring.

As did throughout its report, the Joint Review Panel gave great weight to Northern Gateway’s evidence:

Northern Gateway said that potential effects of oil stranded on the shorelines and in the intertidal environment were assessed qualitatively with particular reference to the Exxon Valdez oil spill. It said that the entire intertidal zone along affected

shorelines would likely be oiled, coating rocks, rockweed, and sessile invertebrates. Some of the diluted bitumen could penetrate coarse-grained intertidal substrates, and could subsequently be remobilized by tides and waves. There were

relatively few shoreline areas with potential for long oil residency. Northern Gateway said that the stranded bitumen would not be uniformly distributed, and that heavy oiling would likely be limited to a small proportion of affected shoreline. Northern

Gateway said that, compared to the Exxon Valdez oil spill, the simulation suggested that more dilbit would be distributed along a shorter length of shoreline.

Northern Gateway said that, due to the relatively sheltered conditions in Wright Sound, and in the absence of cleanup, most of the stranded oil would be weathered or dispersed into the marine environment within 3 to 5 years. It said that,

while weathering and dispersal could represent an important secondary source of hydrocarbon contamination of offshore or subtidal sediments, the weathered hydrocarbons themselves would have lower toxicity than fresh dilbit.

Northern Gateway assessed potential effects on key marine receptors including marine water quality, subtidal sediment quality, intertidal sediment

quality, plankton, fish, and a number of bird and mammal species. The company said that acute effects from monocyclic aromatic hydrocarbons such as benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, and xylene may briefly occur in some areas. Acute effects from polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons were not likely due to their low water solubility.

Northern Gateway said that chronic adverse effects on the subtidal benthic community were not predicted. After a large spill, consumption advisories for pelagic, bottom-dwelling and anadromous fish, and invertebrates from open

water areas and subtidal sediments would probably be less than 1 year in duration. Northern Gateway said that consumption advisories for intertidal communities and associated invertebrates, such as mussels, could persist for 3 to 5 years or longer in

some sheltered areas.

But dilbit is different from heavy crude

In response to questions from the Haisla Nation and the United Fishermen and Allied

Workers Union, Fisheries and Oceans Canada said that, although it had a great deal of information on conventional oils, the results of research conducted on the biological effects of conventional oil products may not be true for dilbit or unconventional products. Fisheries and Oceans Canada said that it was not in a

position to quantify the magnitude and duration of impacts to marine resources

The United Fishermen and Allied Workers Union said that, because there are so many variables, each spill is a unique event, and some results will be unknowable. It said that a spill the size of the Exxon Valdez incident would affect the entire ecosystem

in the project area, and that recovery to pre-spill conditions would be unlikely to ever occur. It said that a spill the size of the Exxon Valdez oil spill would likely have similar effects in the project area because marine resources in the project area are

similar to those in Prince William Sound. It argued that the cold, sheltered, waters of the Confined Channel Assessment Area would likely experience reduced natural dispersion and biodegradation of oil, leading to heavier oiling and longer recovery

times than seen in Prince William Sound and elsewhere.

The United Fishermen and Allied Workers Union said that patches of buried oil from the Exxon Valdez oil have been found on sand and gravel beaches overlain by boulders and cobbles. It said that effects from a tanker spill associated with the

Enbridge Northern Gateway Project would likely be more severe than the Exxon Valdez oil spill due to the more persistent nature of dilbit and the lack of

natural cleaning action in the sheltered waters of the Confined Channel Assessment Area.

The Gitxaala Nation’s experts said that large historical spill events are not necessarily good indicators of what will happen in the future. They

argued that each spill has unique circumstances and there is still significant uncertainty about the effects of major spills.

The Gitxaala Nation concluded Northern Gateway had failed to adequately consider the potential consequences on ecological values of interest to the Gitxaala.

Gitga’at First Nation said that a spill of dilbit greater than 5,000 cubic metres would result in significant, adverse, long-term, lethal, and sublethal effects

to marine organisms, and that effects would be particularly long-lasting on intertidal species and habitats. It also said that effects from a tanker spill associated with the project would probably be more severe than the Exxon Valdez oil spill, due to

the more persistent nature of dilbit and the lack of natural cleaning action in the sheltered waters

The JRP told how Nothern Gateway looked at the scientific evidence:

The company used a case study approach and reviewed the scientific literature for environments similar to the project area. The review examined 48 spills, including the Exxon Valdez oil spill in 1989, and 155 valued ecosystem components from cold temperate and sub-arctic regions. Northern Gateway said that the scientific evidence is clear that, although oil spills have adverse effects on biophysical and human environments, ecosystems and their components recover with time.

Pacific herring, killer whales, and pink salmon were species that were extensively studied following the Exxon Valdez spill and were discussed by numerous participants in the Panel’s process.

As referred to by the Haisla Nation, Pacific herring are listed as “not recovering” by the Exxon Valdez Oil Spill Trustee Council. The Trustee Council said that, despite numerous studies to understand the effects of oil on herring, the causes constraining population recovery are not well understood.

Northern Gateway said that scientific evidence indicates that a combination of factors, including disease, nutrition, predation, and poor recruitment

appear to have contributed to the continued suppression of herring populations in Prince William Sound.

Northern Gateway said that 20 years of research on herring suggests that the Exxon Valdez oil spill is likely to have initially had localized effects on herring eggs and larvae, without causing effects at the population level. Northern Gateway said

that, even after 20 years, the effects of the spill on herring remain uncertain. It said that there has also been convergence amongst researchers that herring declines in the spill area cannot be connected to the spill.

Northern Gateway said that herring stocks along the entire coast of British

Columbia have been in overall decline for years and that herring were shown to recover within 1 to 2 years following the Nestucca barge spill.

A Gitxaala Nation expert noted the uncertainty in interpreting the decline of herring following the Exxon Valdez oil spill and said that the debate is not likely to ever be settled.

The Living Oceans Society said that the Exxon Valdez Oil Spill Trustee Council reported that some killer whale groups suffered long-term damage from initial exposure to the spill. Northern Gateway’s expert said the research leads him to

conclude that the actual effects on killer whales of the Exxon Valdez spill are unknowable due to numerous confounding factors. He said that the

Exxon Valdez Oil Spill Trustee Council has not definitively said that killer whale mortalities can be attributed to the spill. A Government of Canada

expert said that the weight of evidence suggests that the mortality of killer whales was most likely related to the spill.

Northern Gateway said that mass mortality of marine fish following a spill is rare. In response to questions from the Haisla Nation, Northern Gateway said that fish have the ability to metabolize potentially toxic substances such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. It said that international experience with oil spills has demonstrated that fin fishery closures tend to be very short in duration.

Northern Gateway said that food safety programs for fin fish conducted following the Exxon Valdez spill and the Selendang Ayu spill in Alaska indicated

that the finfish were not affected by the spill and that the fish were found, through food safety testing programs, to be safe to eat.

The Haisla Nation referred to the Exxon Valdez Oil Spill Trustee Council report that discussed the complexities and uncertainties in the recovery status of pink salmon. It said that, by 1999, pink salmon were listed as recovered and that the

report noted that continuing exposure of embryos to lingering oil is negligible and unlikely to limit populations.

Northern Gateway said that the longterm effect of the spill on pink salmon survival is

best demonstrated by the success of adult returns following the spill. Northern Gateway said that, in the month following the spill, when there was still

free oil throughout Prince William Sound, hundreds of millions of natural and hatchery pink salmon fry migrated through the area. It argued that these fish would arguably be at greatest risk from spill-related effects but that the adult returns 2 years later were one of the highest populations ever. Northern Gateway said that sockeye and pink salmon appear to have been unaffected by the Exxon Valdez spill

over the long term.

In response to questions from the Council of the Haida Nation and the United Fishermen and Allied Workers Union, Northern Gateway said that effects

on species such as seaweed, crabs, and clams have been shown to be relatively short-term, with these species typically recovering within 2 years or less

following a spill, depending on circumstances.

Northern Gateway said that, based on the Exxon Valdez spill, the level of hydrocarbons dissolved or suspended in the water column would be expected

to be substantially lower than those for which potential toxic effects on crabs or fish may occur.

In response to questions from BC Nature and Nature Canada, Northern Gateway said that the Exxon Valdez oil spill indicates which species of birds are most susceptible to oiling. Seabirds are generally vulnerable to oil spills because many species spend large amounts of time at sea. Diving seabirds such as murres are particularly vulnerable to oiling because they spend most of their time on the surface, where oil is found, and tend to raft together. Thus, these species often account for most of the bird mortality associated with oil spills.

More than 30,000 seabird carcasses, of which 74 per cent were murres, were recovered following the Exxon Valdez spill and it was initially estimated

that between 100,000 and 300,000 seabirds were killed. However, detailed surveys of breeding murres in 1991 indicated no overall difference from pre-spill levels confirming rapid recovery of this species.

Northern Gateway said that, although potential toxicological effects from oil spills on

birds have been well documented in laboratory studies, the ultimate measure of recovery potential is how quickly birds return to their natural abundance and reproductive performance. It said that recovery is often difficult to measure due to

significant natural variation in populations and the fact that the baseline is often disputed. It said that this can lead to misinterpretation of results depicting recovery.

At the request of Environment Canada, Northern Gateway filed two reports on the susceptibility of marine birds to oil and the acute and chronic effects of the Exxon Valdez oil spill on marine birds. Northern Gateway said that marine birds are

vulnerable to oil in several ways such as contact, direct or indirect ingestion, and loss of habitat.

It said that many marine bird populations appear to have recovered from the effects of the Exxon Valdez spill, but some species such as harlequin ducks and pigeon guillemots have not recovered, according to the Exxon Valdez Oil Spill Trustee

Council. It said these reports demonstrate that marine birds are susceptible to marine oil spills to varying degrees depending on the species, its life

history and habitat, and circumstances associated with the spill.

Northern Gateway concluded that:

• Marine, freshwater, and terrestrial environments recover from oil spills, with recovery time influenced by the environment, the valued ecosystem components of interest, and other factors such as spill volume and characteristics

of the oil. Depending on the species and circumstances, recovery can be quite rapid or it can range from 2 to 20 years. Other scientific reviews have indicated that recovery of marine environments from oil spills takes 2 to 10 years.

• Different marine ecosystem components recover at different rates. Recovery time can range from days or weeks in the case of water quality, to years or decades for sheltered, soft sediment marshes. Headlands and exposed rocky shores can take 1 to 4 years to recover.

• Little to no oil remained on the shoreline after 3 years for the vast majority of shoreline oiled following the Exxon Valdez spill,

• The Exxon Valdez Oil Spill Trustee Council concluded that, after 20 years, any remaining Exxon Valdez oil in subtidal sediment is no longer a concern, and that subtidal communities are very likely to have recovered.

• Because sheltered habitats have long recovery times, modern spill response gives high priority to preventing oil from entering marshes and other protected shoreline areas.

• Valued ecosystem components with short life spans can recover relatively rapidly, within days to a few years. Recovery is faster when there is an abundant supply of propagules close to the affected area. For example, drifting larvae from

un-oiled marine and freshwater habitats will rapidly repopulate nearby areas affected by a spill.

• Plankton recovery is typically very rapid.

• Seabed organisms such as filter feeders may be subject to acute effects for several years, depending on location, environmental conditions, and degree of oiling.

• Marine fisheries and other human harvesting activities appear to recover within about 2 to 5 years if the resource has recovered and has not been affected by factors other than the oil spill.

• Protracted litigation may delay resumption of fisheries and other harvesting.

• Local community involvement in spill response priorities and mitigation plans can reduce community impacts and speed recovery of

fisheries and harvesting activities.

• A long life span typically means a long recovery time, in the case of bird and mammal populations that can only recover by local reproduction rather

than by immigration from other areas.

• Fast moving rivers and streams tend to recover more quickly than slow flowing watercourses, due to dispersal of oil into the water column by turbulence, which can enhance dissolution, evaporation, and microbial degradation.

• Drinking water and other water uses can be affected by an oil spill for weeks to months. Drinking water advisories are usually issued. Groundwater use may be restricted for periods ranging from a few weeks to 2 years, depending on

the type of use.

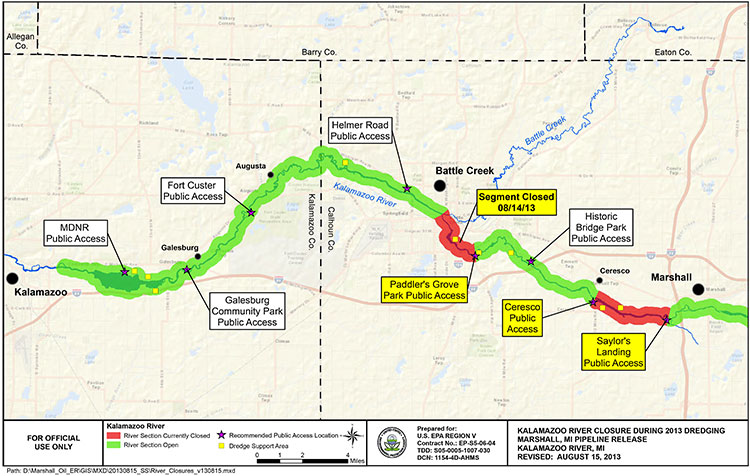

• Groundwater can take years to decades to recover if oil reaches it. Groundwater does not appear to have been affected in the case of Enbridge’s Kalamazoo River spill, near Marshall, Michigan.

• Freshwater invertebrates appear to have recovered within 2 years in several cases.

• Freshwater fisheries may recover fully in as little as four years, with signs of partial recovery evident after only a few months. The ban on consumption of fish in the Kalamazoo River was to be lifted approximately two years following

the spill.

• Human activities are affected by factors such as cleanup activities, safety closures and harvesting bans. These typically persist for months to a few years.

• Appropriate cleanup can promote recovery, while inappropriate cleanup techniques can actually increase biophysical recovery time.

Modern spill response procedures carefully consider the most appropriate treatment for the oil type, level of contamination, and habitat type.

The Living Oceans Society noted the following in relation to potential recovery of the marine environment following a spill:

• Physical contamination and smothering are primary mechanisms that adversely affect marine life, particularly intertidal organisms.

• Birds and mammals suffer the greatest acute impact when exposed to oil at or near the water surface.

• Marine communities have variable resiliency to oil spills, from highly tolerant (plankton, kelp beds), to very intolerant (estuaries and sea otters). Impacts to communities and populations are very difficult to measure due

to lack of scientific methods to measure long term,sublethal, and chronic ecological impacts.

• As the return of the marine environment to the precise conditions that preceded the oil spill is unlikely, a measurement of spill recovery can be

based on a comparison of un-oiled sites with oiled sites of similar ecological characteristics.

• The Exxon Valdez oil spill killed many birds and sea otters. Population-level impacts to salmon, sea otters, harbour seals, and sea birds appear to have been low. Wildlife populations had recovered within their natural range of variability after 12 years.

• Intertidal habitats of Prince William Sound have shown surprisingly good recovery. Many shorelines that were heavily oiled and then cleaned appear much as they did before the spill. There is still residual buried oil on some beaches. Some mussel and clam beds have not fully recovered.

• The marine environment recovered with little intervention beyond initial cleaning. Natural flushing by waves and storms can be more effective than human intervention.

• Wildlife rescue and rehabilitation efforts had a marginal beneficial effect on the recovery of bird and mammal populations

• The impacted area of Prince William Sound had shown surprising resiliency and an ability to return to its natural state within the range of natural variability.

• The Exxon Valdez oil spill had significant and long-lasting effects on people and communities.

Questioning experts

The Panel posed a series of questions to experts representing Northern Gateway, federal government participants, and the Gitxaala First Nation regarding the potential recovery of marine ecosystems following a large oil spill.

Northern Gateway said that past marine spills have demonstrated that, over time, the environment will recover to a pre-spill state, and that most species fully recover. It said that species associated with the surface of the water tend to be most susceptible to oil spills, and that cleanup efforts can help direct and

accelerate natural restoration processes.

Federal government experts generally agreed with Northern Gateway’s responses, although they stressed that effects could be felt in areas other than the water surface, such as intertidal and subtidal zones. They said that it is difficult to define

and assess effects and recovery, depending on the species and availability of baseline information.

They said that most species may fully recover over time, and that the time frame for this recovery can be extremely variable depending on species and circumstances.

The Gitxaala Nation’s experts noted the potential for effects on species at the water surface and in intertidal areas, and noted exceptions to the notion that

the marine environment will naturally restore itself.

They said that full recovery can occur, depending on the circumstances, but is not guaranteed. They said that it is difficult to assess spill effects in the absence

of adequate baseline information.

Despite the quarter century of studies on the Exxon Valdez inicident, the paucity of studies prior to the spill mean that arguments will continue over “baseline information.”

Participants told the Panel that a lack of baseline information has often made it difficult to separate spill-related effects from those that were caused by natural variation or other causes not related to a spill.

Northern Gateway acknowledged the need for adequate baseline information. Parties such as Coastal First Nations, Raincoast Conservation Foundation, and the Gitxaala Nation said that Northern Gateway had provided insufficient baseline information to assess future spill-related effects. The Kitsumkalum First Nation asked how

spill-related effects on traditionally harvested foods could be assessed in the absence of baseline information.

The Haisla Nation noted the importance of collecting baseline data in the Kitimat River valley to compare with construction and spill-related impacts. The Haisla Nation submitted a report outlining important considerations for a baseline

monitoring program. One recommendation was that the program should engage stakeholders and be proponent-funded. In response to questions

from Northern Gateway, the Haisla Nation noted that a design along the lines of a before/after control/impact model would be appropriate.

In response to these comments, Northern Gateway noted its commitment to implement a Pipeline Environmental Effects Monitoring Program. Northern Gateway’s

proposed framework for the monitoring program indicates that a number of water column, sediment, and biological indicators would be monitored.

The Raincoast Conservation Foundation said that one of the principal lessons learned from the Exxon Valdez oil spill was the importance of collecting abundance and distribution data for non-commercial species. Because baseline information was

lacking, spill effects on coastal wildlife were difficult to determine. Environment Canada also noted the importance of adequate baseline information to

assess, for example, spill-related effects on marine birds.

Northern Gateway outlined the baseline measurements that it had already conducted as part of its environmental assessment. It also said that is

would implement a Marine Environmental Effects Monitoring Program. Northern Gateway said that the initial baseline data, plus ongoing monitoring,

would create a good baseline for environmental quality and the abundance, distribution, and diversity of marine biota. In the event of an oil spill

it would also help inform decisions about restoration endpoints.

Northern Gateway said that it would provide Aboriginal groups with the opportunity to undertake baseline harvesting studies. In response to questions from the United Fishermen and Allied Workers Union, Northern Gateway said that baseline information gathered through the environmental effects monitoring program would also be relevant to commercial harvest management and for assessing compensation claims in the event of a spill.

The Kitimat Valley Naturalists noted the ecological importance of the Kitimat River estuary.

The Joint Review Panel, in its conclusions and ruling, generally agreed with the energy industry that affects of a major oil spill would be temporary.

The Panel heard evidence and opinion regarding the value that the public and Aboriginal groups place on a healthy natural environment.

The Panel finds that it is not able to quantify how a spill could affect people’s values and perceptions.

The Panel finds that any large spill would have short-term negative effects on people’s values, perceptions and sense of wellbeing.

The Panel is of the view that implementation of appropriate mitigation and compensation following a spill would lessen these effects over time. The

Panel heard that protracted litigation can delay recovery of the human environment.

The Panel heard that appropriate engagement of communities in determining spill response priorities and developing community mitigation plans can also lessen effects on communities. Northern Gateway has committed to the development

of Community Response Plans

The Panel’s finding regarding ecosystem recovery following a large spill is based on extensive scientific evidence filed by many parties, including information on recovery of the environment from large past spill events such as the Exxon Valdez

oil spill. The Panel notes that different parties sometimes referred to the same studies on environmental recovery after oil spills, and drew different conclusions. In its consideration of natural recovery of the environment, the Panel focused

on effects that are more readily measurable such as population level impacts, harvest levels, or established environmental quality criteria such as

water and sediment quality criteria.

The Panel finds that the evidence indicates that ecosystems will recover over time after a spill and that the post-spill ecosystem will share functional attributes of the pre-spill one. Postspill ecosystems may not be identical to pre-spill ecosystems. Certain ecosystem components may continue to show effects, and residual oil

may remain in some locations. In certain unlikely circumstances, the Panel finds that a localized population or species could potentially be permanently affected by an oil spill. Scientific studies after the Exxon Valdez spill indicated that the vast majority of species recovered following the spill and that functioning ecosystems, similar

to those existing pre-spill, were established.

Species for which recovery is not fully apparent, such as Pacific herring, killer whales, and pigeon guillemots, appear to have been affected by other

environmental factors or human influences not associated with the oil spill. Insufficient pre-spill baseline data on these species contributed to

difficulties in determining the extent of spill effects.

Based on the evidence, the Panel finds that natural recovery of the aquatic environment after an oil spill is likely to be the primary recovery

mechanism, particularly for marine spills. Both freshwater and marine ecosystem recovery is further mitigated where cleanup is possible, effective, and beneficial to the environment.

Natural processes that degrade oil would begin immediately following a spill. Although residual oil could remain buried in sediments for years, the Panel finds that toxicity associated with that oil would decline over time and would not cause

widespread, long-term impacts.

The Panel finds that Northern Gateway’s commitment to use human interventions,

including available spill response technologies, would mitigate spill impacts to ecosystems and assist in species recovery. Many parties expressed concerns about potential short-term and long-term spill effects on resources that they use or depend on, such as drinking water, clams, herring, seaweed, and fish. The weight of

evidence indicates that these resources recover relatively rapidly following a large oil spill.

For example, following the Selendang Ayu and Exxon Valdez spills in Alaska, fin fish were found, through food safety testing programs, to be safe to eat. Food safety closures for species such as mussels, urchins, and crabs were lifted within 1 to

2 years following the spills.

The actual time frame for recovery would depend on the circumstances of the spill. Until harvestable resources recover, various measures are typically put in place, such as compensation,harvest restrictions or closures, and provision of

alternative supply.

It is difficult to define recovery of the human environment because people’s perceptions and values are involved. This was made clear to the

Panel through oral statements and oral evidence.

The Panel finds that oil spills would cause disruptions in people’s lives, especially those people who depend on the marine environment for sustenance, commercial activities and other uses. The extent and magnitude of this disruption

would depend on the specific circumstances associated with the spill. The Panel views recovery of the socio-economic environment as the time when immediate impacts and interruption to people’s lives are no longer evident, and the

natural resources upon which people depend are available for use and consumption.

The Panel heard that assessing the potential recovery time of the environment is often complicated by challenges in separating background or unrelated events from spill-related effects. There can be natural variation in species populations,

and other natural and human-induced effects can also make it difficult to determine which impacts are spill-related and which are not.

The Panel notes that Northern Gateway has committed to collect baseline data and gather baseline information on harvest levels and values through initiatives such as its Environmental Effects Monitoring Program, Fisheries Liaison

Committee, and traditional harvest studies. The Panel finds that these commitments go beyond regulatory requirements and are necessary. This information would contribute to assessments of spill effects on resource harvesting values,

post-spill environmental recovery, and loss and liability determinations.

The Panel is of the view that it is not possible to predict a specific time in which overall recovery of the environment may occur. The time for recovery would depend on the type and volume of product spilled, environmental conditions,

the success of oil spill response and cleanup measures, and the extent of exposure of living and non-living components of the environment to the product spilled. Recovery of living and non-living components of the environment would

occur over different time frames ranging from weeks, to years, and in the extreme, decades.

Even within the same environmental component, recovery may occur over different time frames depending on local factors such as geographic location, the amount of oiling, success of cleanup, and amount of natural degradation.

Based on the physical and chemical characteristics described for the diluted bitumen to be shipped and the fate and transport modelling conducted, the Panel finds that stranded oil on shorelines would not be uniformly distributed on

shorelines and that heavy oiling would be limited to specific shoreline areas. The Panel accepts Northern Gateway’s prediction that spilled dilbit could persist longer in sheltered areas, resulting in longer consumption advisories for intertidal

communities and associated invertebrates than in more open areas.

Based on the scientific evidence, the Panel accepts the results of the

chronic risk assessment that predicted no significant risks to marine life due to oil deposition in the subtidal sediments.

For potential terrestrial and marine spills, the Panel does not view reversibility as a reasonable measure against which to predict ecosystem recovery. No ecosystem is static and it is unlikely that an ecosystem will return to exactly the same

state following any natural or human induced disruption. Based on the evidence and the Panel’s technical expertise, it has evaluated whether or not functioning ecosystems are likely to return after a spill. Requiring Northern Gateway to

collect baseline data would provide important information to compare ecosystem functions before and after any potential spill.

The Panel finds that Northern Gateway’s ecological and human health risk assessment models and techniques were conducted using conservative assumptions and state of the art models. Combined with information from past spill events, these assessments provided sufficient information to inform the Panel’s deliberation on

the extent and severity of potential environmental effects. The Panel finds that this knowledge was incorporated in Northern Gateway’s spill prevention strategies and spill preparedness and response planning. Although the ecological risk assessment

models used by Northern Gateway may not replicate all possible environmental conditions or effects, the spill simulations conducted by Northern Gateway provided a useful indication of the potential range of consequences of large oil spills in

complex natural environments.