In its extensive document filed with the Northern Gateway Joint Review panel, the Haisla Nation emphasize their opposition to the project.

In its extensive document filed with the Northern Gateway Joint Review panel, the Haisla Nation emphasize their opposition to the project.

However, the Haisla are anticipating that the project will be approved and therefore submitted a lengthy series of conditions for that project, should it be imposed on the northwest by the federal government.

Nevertheless, if the project were to be approved AFTER the Crown meaningfully consulted and accommodated the Haisla Nation with respect to the impacts of the proposed project on its aboriginal title and rights, and if that consultation were meaningful yet did not result in changes to the proposed project, the following conditions would, at a minimum, have to be attached to the project.

1. Conditions Precedent: The following conditions precedent should be met prior to any field investigations, pre-construction activities or construction activities as well as during and subsequent to such investigations or activities. These conditions are necessary to ensure that potential effects of the project can be avoided or mitigated to reduce the likelihood of habitat damage or destruction:

Comprehensive seasonal water quality monitoring throughout the Kitimat River watershed, Kitimat Arm and Douglas Channel that account for seasonal variations in flow, tidal cycles, snowmelt, rainfall, etc.

Parameters for measurement would be have to be agreed upon by the

Haisla Nation prior to certification of the project;

Comprehensive seasonal fisheries surveys of fish habitat utilization throughout the Kitimat River watershed, Kitimat Arm and Douglas Channel that account for where species and life stages are at different times of the year and accurately define sensitive habitats;

Comprehensive seasonal wildlife and bird surveys of habitat utilization throughout the Kitimat River watershed, Kitimat Arm and Douglas Channel that account for where species and life stages are at different times of the year and accurately define sensitive habitats;

Comprehensive seasonal vegetation surveys of habitat utilization throughout the Kitimat River watershed, Kitimat Arm and Douglas Channel that accounts for the distribution of species and life stages at different times of the year and accurately define sensitive habitats;

Development of comprehensive spill response capability based on a realistic assessment of spill containment, spill response and spill capacity requirements throughout the Kitimat River Valley, Kitmat Arm and Douglas Channel. The Haisla Nation’s past experience has shown that relying onpromises is not good enough. This spill response capability must be demonstrated prior to project approval;

Verification that the proposed project would result in real benefits, economic or otherwise, that would flow to the Haisla Nation, to other First Nations, and to British Columbia.

Whenever any field investigations or activities are proposed, the proposal or permit application would have to include the following environmental protections:

Soil and erosion control plans;

Surface water management and treatment plans;

Groundwater monitoring plans;

Control and storage plans for fuels, lubricants and other potential contaminants;

Equipment deployment, access and use plans;

Habitat reclamation of disturbed or cleared areas.

Prior to any pre-construction or construction activities the following detailed studies would have to be undertaken and provided to the Haisla Nation for review and approval, to ensure that the best design and construction approaches are being used, so that potential effects of the project can be avoided or mitigated to reduce the likelihood of habitat damage or destruction:

Detailed analysis of terrain stability and slide potential throughout the pipeline corridor and at the storage tank and terminal site;

Detailed engineering design to mitigate seismic risk and local weather extremes;

.Development of pipeline integrity specifications and procedures including

best practices for leak detection;

Development of storage tank integrity specifications and maintenance and monitoring procedures;

Assessment of spill containment, spill response and spill capacity requirements throughout the Kitimat River watershed, Kitimat Arm and Douglas Channel;

.Development of detailed tanker acceptance program specifications and

procedures;

Development of detailed tanker and tug traffic management specifications and procedures;

Development of detailed port management specifications and procedures including operating limits for tanker operation, movement and docking.

2. Ongoing Consultation: A commitment to ongoing consultation with and accommodation of the Haisla Nation on all of the activities set out above.

3. Ongoing process for variance, waiver or discharge of conditions: A commitment to ongoing meaningful involvement of the Haisla Nation by the National Energy Board prior to any decision on any changes to or sign off on conditions and commitments to any certificate that is issued.

4. Third Party Oversight of Construction: A requirement that NorthernGateway fund a third party oversight committee, which should include a Haisla Nation representative, to monitor certificate compliance during construction of the marine terminal and the pipeline. This committee would have the ability to monitor and inspect construction and should be provided with copies of allcompliance documents submitted by Northern Gateway to the National Energy Board.

5. Operational Conditions: A number of operational conditions should beincorporated into the certificate, including but not limited to:

The requirement to monitor terrain along the pipeline so that breaches based on earth movements can be anticipated and prevented;

The requirement to implement automatic pipeline shutdown whenever a leak detection alarm occurs;

Conditions on the disposal of any contamination that must be removed as a result of an accident or malfunction resulting in a spill that will minimize additional habitat destruction and maximize the potential for regeneration of habitat and resources damaged by the spill;

Parameters for terminal and tanker operations (including standards for tankers allowed to transport cargo; tanker inspection requirements and schedules; escort tug specifications, standards, maintenance and inspection; pilotage protocols and procedures; environmental conditions and operating limits; etc.) as well as other parameters set out in and reliedon for the TERMPOL review to become conditions of any certificate issued by the National Energy Board, with a provision that the Haisla Nation’s approval of any changes to these conditions is required.

Answering the questions from Enbridge Northern Gateway, the Haisla also outline a long series of concerns.

1. Physical and Jurisdictional Impacts

1.1 Construction

The Haisla Nation is concerned about the direct physical and jurisdictional impacts that the construction of the proposed project will have. These concerns are set out for each of the marine terminal, the pipeline, and tanker traffic, below:

Marine Terminal:

a. The proposed marine terminal will require the alienation of 220-275

hectares (554-680 acres) of land from Haisla Nation Territory, land

to which the Haisla Nation claims aboriginal title.

b. The terminal will require the additional alienation of land for

ancillary infrastructure and development, including:

i. road upgrades,

ii. perimeter access roads and roads within the terminal area,

iii. a potential public bypass road,

iv. an impoundment reservoir,

v. a disposal site for excess cut material outside the terminal

area,

vi. a new 10km long transmission powerline, and

vii. a 100-m waterlot with a 150-m “safety zone”.

c. The terminal proposes to use Haisla Nation aboriginal title land,

including foreshore and waters, in a way that is inconsistent with

Haisla Nation stewardship of its lands, waters and resources and

with the Haisla Nation’s own aspirations for the use of this land.

Since aboriginal title is a constitutionally protected right to use the

aboriginal title land for the purposes the Haisla Nation sees fit, this

adverse use would fundamentally infringe the aboriginal title of the

Haisla Nation.

d. The terminal will require the destruction and removal of

documented culturally modified trees, some with modifications

dating back to 1754. These culturally modified trees are living

monuments to the history of the Haisla people.

e. The terminal will expose two Haisla Nation cultural heritage sites to

increased risk of vandalism and chemical weathering.

f. The terminal will result in the direct loss of 4.85 hectares (11.98

acres) of freshwater fish habitat (harmful alteration, disruption or

destruction (HADD) under the Fisheries Act).

g. The terminal will require dredging, underwater blasting, and

placement of piles and berthing foundations, resulting in an as yet

un-quantified loss of intertidal and subtidal marine habitat.

Pipeline:

a. The proposed pipeline construction right-of-way will require the

alienation of 9,200 hectares (22,734 acres) of Haisla Nation

Territory – land to which the Haisla Nation claims aboriginal title –

and will put this land to a use that is inconsistent with Haisla Nation

stewardship of its lands, waters and resources and with the Haisla

Nation’s own aspirations for the use of this land.

b. The pipeline will require 127 watercourse crossings in Haisla Nation

Territory. Seven of these are categorized as high risk, 5 as

medium high risk, and 7 are medium or medium low risk for harmful

alternation, disruption or destruction (HADD) of fish habitat. This

risk is just from pipeline construction and does not address the

issue of spills.

c. The pipeline is estimated to result in temporary or permanent

destruction of freshwater fish habitat of 3.1 hectares (7.68 acres) in

Haisla Nation Territory.

d. The pipeline will require the clearing of land and vegetation and the

destruction of wetlands. The extent of this is yet to be quantified.

Tanker Traffic:

a. Although Northern Gateway has not made any submission on this

point, it is clear that having adequate spill response capability at

Kitimat will require additional infrastructure upgrades in and around

Kitimat, as well as potential spill response equipment cache sites.

None of this has been considered or addressed in Northern

Gateway’s application material – as such the material is

incomplete.

b. The construction for this additional infrastructure could result

impacts to ecosystems, plants, wildlife and fish, and in additional

HADD or fish mortality from accidents.

All of the land alienations required for the proposed project would profoundly

infringe Haisla Nation aboriginal title which is, in effect, a constitutionally

protected ownership right. The proposed project would use Haisla Nation

aboriginal title land in a way that is inconsistent with Haisla Nation stewardship of

its lands, waters and resources and with the Haisla Nation’s own aspirations for

the use of this land. Since aboriginal title is a constitutionally protected right to

use the aboriginal title land for the purposes the Haisla Nation sees fit, this

adverse use would fundamentally infringe the aboriginal title of the Haisla Nation.

The Haisla Nation is also concerned about the socio-economic and health

impacts of the proposed project. Northern Gateway has yet to file its Human

Health and Ecological Risk Assessment. Further, the socio-economic impact

analysis submitted as part of the application provides only a limited assessment

of the potential impacts of the project on the Haisla Nation at a socio-economic

level.

Haisla Nation society and economy must be understood within the cultural

context of a people who have lived off the lands, waters and resources of their

Territory since long before European arrival. To limit a socio-economic impact

assessment to direct impacts and to ignore consequential impacts flowing from

those impacts fails to capture the potential impacts of the proposed project on the

Haisla Nation at a socio-economic level.

1.2 Operation

The proposed marine terminal, pipeline corridor and shipping lanes will be

located in highly sensitive habitats for fish, wildlife and plants. Any accident of

malfunction at the wrong time in the wrong place can be devastating ecologically.

The Haisla Nation has identified the following concerns relating to physical

impacts from the operation of the proposed project:

Marine Terminal:

a. Intertidal and subtidal marine habitat impacts as a result of marine

vessels.

b. The likelihood of spills from the marine terminal as a result of operational

mistakes or geohazards.

c. The effects and consequences of a spill from the marine terminal. This

includes impacts on the terrestrial and intertidal and subtidal marine

environment and fish, marine mammals, birds, and other wildlife, as well

as impacts on Haisla Nation culture and cultural heritage that could result

from such impacts.

d. Response to a spill from the marine terminal, including concerns about

spill response knowledge, planning and capability, as well as impacts

flowing from response measures themselves.

Pipeline:

a. The likelihood of spills from the pipeline as a result of pipeline failure,

resulting from inherent pipeline integrity issues or external risks to pipeline

integrity, such as geohazards.

b. The effects and consequences of a spill from the pipelines. This includes

impacts on the terrestrial environment and freshwater environment, and

on plants, fish, birds, and other wildlife, as well as impacts on Haisla

Nation culture and cultural heritage that could result from such impacts.

c. Response to a spill from the pipelines, including concerns about spill

response knowledge, planning and capability, as well as impacts flowing

from response measures themselves.

Tanker Traffic:

a. Increased vessel traffic in waters used by Haisla Nation members for

commercial fishing and for traditional fishing, hunting and food gathering.

b. The likelihood of spills, including condensate, diluted bitumen, synthetic

crude, and bunker C fuel and other service fuels, from the tankers at sea

and at the marine terminal.

c. The effects and consequences of a spill. This includes impacts on the

marine environment and fish, marine mammals, birds, and other wildlife,

as well as impacts on Haisla Nation culture and cultural heritage that could

result from such impacts.

d. Response to a spill, including concerns about spill response knowledge,

planning and capability, as well as impacts flowing from response

measures themselves.

e. Potential releases of bilge water, with concerns about oily product and

foreign organisms.

These issues are important. They go to the very heart of Haisla Nation culture.

They go to the Haisla Nation relationship with the lands, waters, and resources of

its Territory. A major spill from the pipeline at the marine terminal or from a

tanker threatens to sever us from or damage our lifestyle built on harvesting and

gathering seafood and resources throughout our Territory.

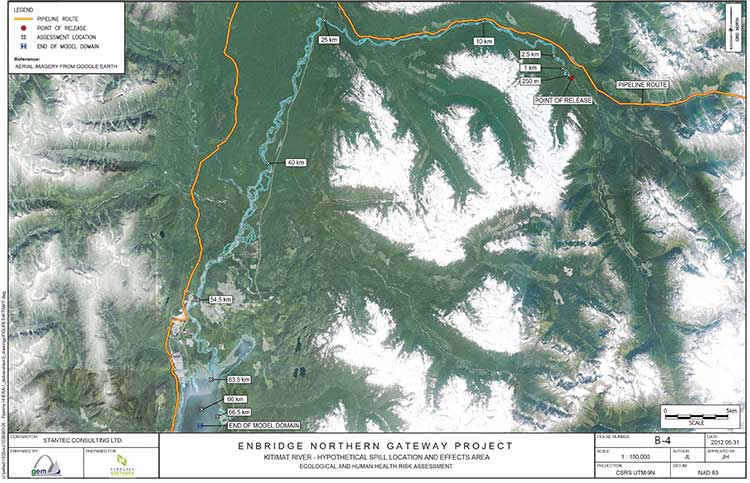

Northern Gateway proposes a pipeline across numerous tributaries to the Kitimat

River. A spill into these watercourses is likely to eventually occur. The evidence

before the Panel shows that pipeline leaks or spills occur with depressing

regularity.

One of Enbridge’s own experiences, when it dumped 3,785,400 liters of diluted

bitumen into the Kalamazoo River, shows that the concern of a spill is real and

not hypothetical. A thorough understanding of this incident is critical to the

current environmental assessment since diluted bitumen is what Northern

Gateway proposes to transport. However, nothing was provided in the application

materials to address the scope of impact, the level of effort required for cleanup

and the prolonged effort required to restore the river. An analysis of this incident

would provide a basis for determining what should be in place to maintain

pipeline integrity as well as what should be in place locally to respond to any spill.

The Kalamazoo spill was aggravated by an inability to detect the spill, by an

inability to respond quickly and effectively, and by an inability to predict the fate

of the diluted bitumen in the environment. As a result, the Kalamazoo River has

suffered significant environmental damage. The long-term cumulative

environmental damage from this spill is yet to be determined.

Further, the Haisla Nation is also concerned about health impacts of the

proposed project and awaits the Human Health and Ecological Risk Assessment

which Northern Gateway has promised to provide.

1.3 Decommissioning

Northern Gateway has not provided information on decommissioning that is detailed enough to allow the Haisla Nation to set out all its concerns about the potential impacts from decommissioning at this point in time. This is not good enough. The Haisla Nation needs to know how Northern Gateway proposes to undertake decommissioning, what the impacts will be, and that there will be financial security in place to ensure this is done properly.

2. Lack of Consultation

Broadly, the Haisla Nation has concerns about all three physical aspects of the

proposed project – the pipeline, the marine terminal and tanker traffic – during all

three phases of the project – construction, operation and decommissioning.

These concerns have not been captured or addressed by Northern Gateway’s

proposed mitigation. The Haisla Nation acknowledges that a number of these

concerns can only be addressed through meaningful consultation with the

Crown. The Haisla Nation has therefore repeatedly asked federal decision-

makers to commit to the joint development of a meaningful consultation process

with the Haisla Nation. The federal Crown decision-makers have made it very

clear that they have no intention of meeting with the Haisla Nation until the Joint

Review Panel’s review of the proposed project is complete.

The federal Crown has also stated that it is relying on consultation by NorthernGateway to the extent possible. The federal Crown has failed to provide anyclarity, however, about what procedural aspects of consultation it has delegated to Northern Gateway. Northern Gateway has not consulted with the Haisla Nation and has not advised the Haisla Nation that Canada has delegated any aspects of the consultation process.

The Haisla Nation asserts aboriginal title to its Territory. Since the essence of

aboriginal title is the right of the aboriginal title holder to use land according to its

own discretion, Haisla Nation aboriginal title entails a constitutionally protected

ability of the Haisla Nation to make decisions concerning land and resource use

within Haisla Nation Territory. Any government decision concerning lands,

waters, and resource use within Haisla Nation Territory that conflicts with a

Haisla lands, waters or resources use decision is only valid to the extent that the

government can justify this infringement of Haisla Nation aboriginal title.

The Supreme Court of Canada has established that infringements of aboriginal

title can only be justified if there has been, in the case of relatively minor

infringements, consultation with the First Nation. Most infringements will require

something much deeper than consultation if the infringement is to be justified.

The Supreme Court has noted that in certain circumstances the consent of the

aboriginal nation may be required. Further, compensation will ordinarily be

required if an infringement of aboriginal title is to be justified [Delgamuukw].

The Haisla Nation has a chosen use for the proposed terminal site. This land

was selected in the Haisla Nation’s treaty land offer submitted to British Columbia

and Canada in 2005, as part of the BC Treaty Negotiation process, as lands

earmarked for Haisla Nation economic development.

The Haisla Nation has had discussions with the provincial Crown seeking to

acquire these lands for economic development purposes for a liquefied natural

gas project. The Haisla Nation has had discussions with potential partners about

locating a liquefied natural gas facility on the site that Northern Gateway

proposes to acquire for the marine terminal. The Haisla Nation sees these lands

as appropriate for a liquefied natural gas project as such a project is not nearly

as detrimental to the environment as a diluted bitumen export project. This use,

therefore, is far more compatible with Haisla Nation stewardship of its lands,

waters and resources.

By proposing to use Haisla Nation aboriginal title land in a manner that is

inconsistent with Haisla Nation stewardship of its lands, waters and resources,

and that interferes with the Haisla Nation’s own proposed reasonable economic

development aspirations for the land, the proposed project would result in a

fundamental breach of the Haisla Nation’s constitutionally protected aboriginal

title.

Similarly, Haisla Nation aboriginal rights are constitutionally protected rights to

engage in certain activities (e.g. hunting, fishing, gathering) within Haisla Nation

Territory. Government decisions that infringe Haisla Nation aboriginal rights will

be illegal unless the Crown can meet the stringent test for justifying an

infringement.

Main story Haisla Nation confirms it opposes Northern Gateway, demands Ottawa veto Enbridge pipeline; First Nation also outlines “minimum conditions” if Ottawa approves the project

Haisla Nation Response to NGP Information Request (pdf)

A new US report is slamming Enbridge for its record on oil spills, just as the BC government set out strict new conditions for building pipelines and tanker traffic in the province.

A new US report is slamming Enbridge for its record on oil spills, just as the BC government set out strict new conditions for building pipelines and tanker traffic in the province.